In the latest IMF Finance and Development journal (March 2023), there is an interesting article by the former governor of the Bank of Japan, Masaaki Shirakawa – It’s time to rethink the foundation and framework of monetary policy. It goes to the heart of the complete confusion that is now being demonstrated by central bank policy makers. With their ‘one trick pony’ interest rate attacks on inflation, not only have they been inconsequential in dealing with that target (the so-called price stability responsibility), but, in failing there, they have undermined the achievement of the other central bank target (financial stability) and probably worsened the chances of sustaining the third target (full employment). Sounds like a mess – and it is. We are witnessing what happens when Groupthink finally takes over an academic discipline and the policy making space. Blind, unidirectional policies, based on a failed framework, steadily undermining all the major goals – that is where we are right now. And not unsurprisingly, those who have previously preached the doctrine are now crossing the line and joining with those who predicted this mess. And, as usual, the renegade position is somehow recast as we knew it all along’ when, of course, they didn’t. When you get to that stage, we need music – and given it is Wednesday, I oblige at the end of this post.

Former Bank of Japan governor questions mainstream monetary consensus

Masaaki Shirakawa, while staying firmly within the mainstream paradigm, essentially questions the dominance of that framework.

He noted that a speech by US Federal Reserve boss in August 2020 (at Jackson Hole) represented the orthodoxy, that is now driving central banks to push up rates, which, in turn, appear to be destabilising the global banking system.

So not only are the rate rises not doing much to curb an inflationary period that is driven largely by factors that are interest-rate insensitive, but the inintended consequences of the rate rises are driving poorly managed banks broke.

Masaaki Shirakawa concluded that while Powell’s mainstream analysis dominates, the ‘experience’ of Japan:

… casts doubt on the validity of the narrative.

Why?

1. Japan has had zero interest rates long before the other economies went there but:

… if this had been a serious constraint on policy, Japan’s growth rate should have been lower than that of its Group of Seven (G7) peers. Yet growth of Japanese GDP per person was in line with the G7 average from 2000 (about the time the Bank of Japan’s interest rates reached zero and the central bank began unconventional monetary policy) to 2012 (just before the central bank’s balance sheet started to balloon). Growth of Japan’s GDP per working-age person was the highest among the G7 during the same period.

I discussed this point in a paper I gave at Kyoto University last November which will be published in a different form soon.

You can see a draft of the paper – William_Mitchell_Comparative_Study_Australia_Japan (PDF – 455 kbs).

The point being made by the former governor really dismisses the standard Western line about the ‘lost decade’ or two in Japan.

For a lost decade or two, Japan has managed to maintain comparable GDP per capita growth and very low unemployment, which is not something we can say about the other Western economies.

2. Japan engaged in earlier and larger QE than other nations and:

The Bank of Japan’s “great monetary experiment” in the years following 2013, during which the central bank’s balance sheet expanded from 30 percent to 120 percent of GDP, is again telling. On the inflation front, the impact was modest.

He also points out that once “many other countries” followed suit and started buying up government bonds to keep yields low and play the private speculators out of the game (effectively) the same policy outcomes occurred (virtually no inflation impact), so it was not just a Japanese-centric outcome.

So the claim that using aggressive fiscal policy supported by central banks maintaining control of the bond markets will reduce growth and force up interest rates and inflation are not consistent with the historical data.

3. He further casts doubt on the ‘Great Moderation’ narrative which claims that the stable inflation period during the 1990s and on was the work of inflation-targetting central banks and justified all the todo about ‘independent central banks’ and the subjugation of fiscal policy (the austerity mindset).

He wrote:

The prevalent narrative of successful monetary policy conducted by independent central banks during that period may have come down to good luck and fortuitous circumstances.

He points to factors outside the purview of central bankers discretion as fundamental for the stability experienced during this period – “benign supply-side factors … rapid advanvces in information technology, and a relatively stable geopolitical environment.”

All of which are now in retreat.

The comparison between the inflation dynamics in Japan and the US is instructive.

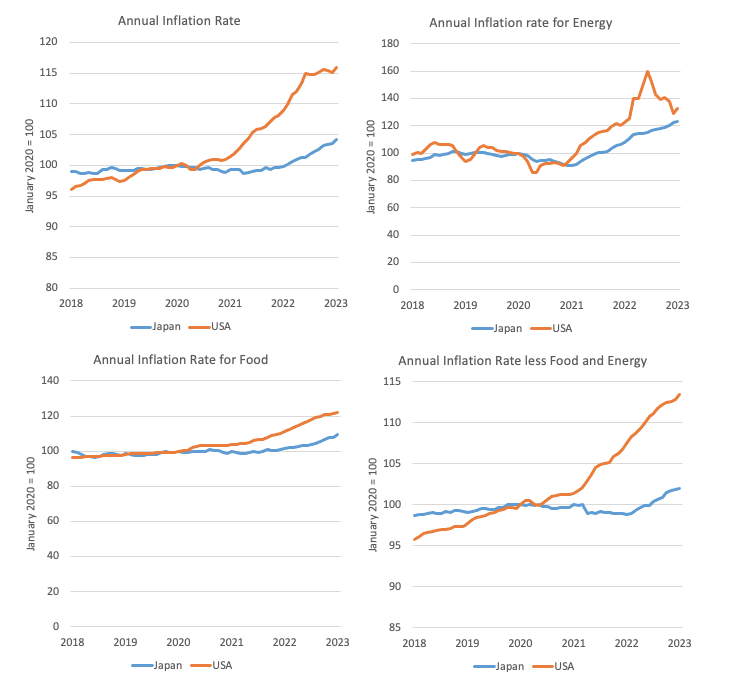

The following four-panel graph captures the key aggregates from January 2018 to January 2023.

The indexes are set to 100 in January 2020.

The US inflation rate accelerated in December 2020.

Since then (to January 2023), the US All Items CPI has expanded by 14.9 per cent while Japan’s equivalent index has risen by 5.4 per cent.

Over that same period, energy prices in the US rose by 42.9 per cent, and by 35.3 per cent in Japan.

Food prices by 18.2 per cent in the US and 10.8 per cent in Japan.

Taking out these volatile items, the All Items less food and energy index rose by 12.2 per cent in the US, and 2.2 per cent in Japan.

A fundamental difference.

And interest rates have risen significantly in the US and by zero per cent in Japan.

To see how fiscal policy impacts, we can examine the sub-group components of the All Items CPI for Japan.

The Communication component index has fallen from 100.5 points in January 2021 to 71.1 points by January 2023 – a decline of 29.3 per cent over the two-year period.

We should also note that according to the Bank of Japan (Source):

… the information and communications industry, both … face a severe labor shortage

Mainstream economists would be claiming that such a severe shortage should be pushing up unit labour costs and driving that CPI component up.

So, why has there been such a large decline in communication costs?

The reason is that there has been a “drastic drop in mobile phone communication charges” (Source).

Okay, why?

Fiscal policy – that’s why.

In October 2020, the Minister for Internal Affairs and Communications (MIC) announced that it intended to drive down mobile phone charge by pressuring the telco carriers to push down mobile phone costs to consumers.

On December 4, 2020, it was announced that MIC, the Japan Fair Trade Commission (JFTC) and the Consumer Affairs Agency (CAA) would cooperate on this venture – see announcement – Two Ministers’ Meeting for Reducing of Mobile Phone Charges.

The plan involved making it easier to shift between mobile providers, provision of more information and other strategies.

The campaign to persuade/pressure the telcos worked very well.

While the Communications component is a relatively low weight in the overall index, it does show how fiscal and regulative policy can be used to reduce overall price pressures.

By late April 2022, the initiative was estimated to have taken about 1.4 per cent off the headline inflation rate, which is significant (Source).

The case for fiscal dominance is growing

Previous critics of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) critic, are now writing about how important fiscal policy is and how poor monetary policy is for dealing with inflation.

And article that appeared yesterday (March 21, 2023)- Tax increases are the best cure for inflation – seems to fit that bill.

The authors clearly implicate the Federal Reserve interest rate hikes in the turmoil that has hit the banking system in the last week.

In noting that they ask:

… why exactly interest rate hikes have become the world’s preferred anti-inflationary measure.

Which is a question I have posed regularly over the course of this blog (19 years and still going).

The majority of economists claim that assigning the major responsibilities for aggregate policy to central banks ensured that the policy was ‘depoliticised’ and had the best chance of dealing with fluctuations in spending up and down.

This was really an elaborate smokescreen to degrade the use of fiscal policy (unless it was bailing out one shareholder group or another and validating massive executive salaries).

Dare mention the idea that governments should use fiscal policy to reduce unemployment or provide cash transfers to the poor to life them out of poverty and the screams were deafening.

All the noise about insolvency, skyrocketing interest rates, bond market retaliation, inflation and intergenerational debt burdens reached crescendos when that sort of fiscal policy use was suggested.

But enter a bank in trouble and the fiscal largesse in the trillions can’t get out the door quickly enough.

So we have been living through this period of ideology and we have a pretty good monetary policy track record to reflect on.

Reliance on monetary policy (other than when bailouts were necessary) has not only been ineffective to say the least but has also created many chronic imbalances and poor management decisions by financial institutions (banks etc).

The mess we are in now is testament to that.

Rising rates have exposed poor portfolio decisions by commercial bank managers who now come cap in hand for bail outs.

The foreign currency swaps announced earlier this week have hardly been taken up, simply because commercial banks rarely have foreign currency risk exposure.

Another example of poorly conceived monetary intervention.

But Japan has shown us clearly now that they can deal with an inflationary surge primarily coming through imported food and energy costs and primarily sourced from supply-side factors (pandemic, cartel behaviour etc) without pushing up rates and compromising their banks.

They can get the nation through the cost-of-living squeeze without further hurting debtors by appropriate use of fiscal policy and regulation.

The article cited above though continues to push the mainstream myth that “inflation is a question of too much money chasing too little goods and services, resulting in increases in prices.”

This is the Milton Friedman line.

However, they depart from the monetary policy cure by noting the problem with “long and variable lags” in decision and impact and also that interest rate hikes, if they work, damage investment spending (which is necessary to increase productivity and lower unit costs over time).

The general point that I agree with is that governments should do everything possible to avoid overseeing a recession.

Recessions have long-lived effects, not the least being the impact on potential productive capacity, as business investment stalls.

It also pushed unemployment up quickly and it takes an age to re-absorb that idle labour in the recovery as new entrants keep coming out of the schooling system.

So a policy that deliberately sets out to stifle demand (spending), and, ultimately, create a recession if need be is a very costly strategy.

Moreover, when the inflationary pressures are not much to do with excessive spending, then relying on a policy that attempts to reduce spending is crazy.

The article above considers it would be better to raise taxes to reduce spending.

If excessive demand was the problem then I agree.

At present there is booming demand for luxury motor vehicles.

The low-paid are not contributing to that binge.

There are many options as to which parts of the tax structure one could alter.

But I would not be advocating tax increases right now because the major inflationary issue has been supply-side factors.

If we wanted to reduce inequality and reduce the power of the high income groups then fine – invoke a tax rise on that cohort.

But that is a different discussion to what we should be doing about inflation.

Conclusion

My solution:

1. Be patient.

2. Keep interest rates low.

3. Use targetted fiscal intervention to ensure low-income families and individuals face less cost-of-living pressure (cash transfers etc).

4. Put price caps on energy resources that are domestically produced or a super profits tax on private lease holders who are gouging profits at present and taking advantage of the war in Ukraine.

5. Announce free public transport (I will write about this another day).

6. Cut government charges for child care, education, and other services.

7. Nationalise banks.

And some more.

Music – Classic R&B from the 1960s

This is what I have been listening to while working this morning.

This was one of the earliest albums I seemed to have acquired although my first exposure to it was playing the version my older brother had.

The Rolling Stones released – Out of Our Heads – on the Decca label on September 24, 1965 and it was one of those short albums that were common in those days (33:24 minutes).

In terms of covers, Australia received the US cover, while the Decca version had a different cover (and one which would show up on a later album – December’s Children – released by the band that arrived in Australia).

This was their third studio album and continued their development of British interpretations of American blues and R&B, although the original tracks were starting to enter the picture (4 out of 12 tracks).

But it was classic R&B and I learned a lot of guitar riffs off that album as I got older.

And this was their first number 100 on the US Billboard 200 rankings.

The sound was sophisticated relative to their previous albums, not in the least because Ian Stewart played piano and Jack Nitzsche played organ on some of the tracks.

This song – That’s How Strong My Love Is – written by – Roosevelt Jamison – has remained one of my favourite tracks.

Otis Redding released a cover of the song in the same year as the Rolling Stones, and while I like his version a lot, the Stones version is the best.

It has been extensively covered since.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2023 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.