I was at the optometrist the other day getting my regular eye test and all the person doing the test wanted to talk about was whether we were heading into recession. I think he was toying with buying a new apartment to live in and was trying to assess risk with the rising interest rate regime and all the negative talk. I actually don’t like giving that sort of advice to people I am dealing with in that sort of relationship. But it is a good question – and there is evidence either way. First, it is clear that governments can always protect employment, incomes and business solvency with appropriate fiscal policy interventions. Second, it is less clear on what monetary policy does and that is the issue – eventually interest rate rises will cause certain sectors, such as construction, to encounter difficulties and start laying off workers and recording bankruptcies. But the problem is that monetary policy is such a crude instrument that the damage is done before we really can measure it.

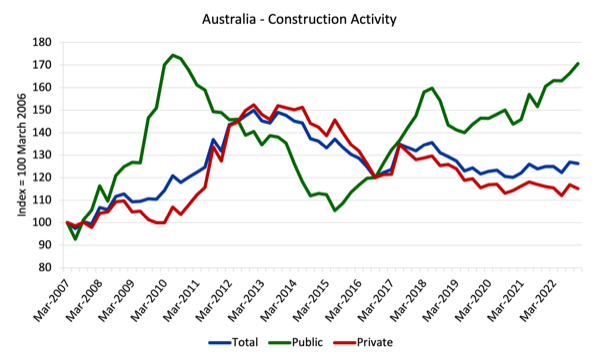

The first graph shows the construction activity in Australia since the March-quarter 2007 up to the December-quarter 2022 (latest data available).

The cyclical nature of fiscal policy is well demonstrated.

The GFC threat to the economy was treated very differently by the federal government ito the 1991 recession where very little support was given until it was too late (see below).

During the GFC government brought in two very large fiscal stimulus measures almost immediately – the home insulation program and the school buildings program – which provided a very large boost to public sector construction activity and effectively offset the slowdown in private construction during the first year and a half after the Lehmans collapse.

That meant that the total construction sector defied its usual status of leading the economy into a deep recession.

The fiscal stimulus kept the construction industry alive and construction employment expanded during that period.

By the time the stimulus was withdrawn, the pessimism in the private sector had abated and you can see activity increased and took over from the public construction boost.

The pandemic is different again.

The fiscal stimulus that was announced in the early period of the 2020 was much smaller than the GFC stimulus from government and largely targetted at private residential construction as opposed to public sector infrastructure development.

While it did prevent a major downturn in the construction industry, it really just held the fort.

And, of course, in the last year, the industry has been hit with 10-successive monthly interest rate hikes from the central bank.

The current period is interesting.

Up until the end of 2022, the total sector has not showed signs of wiling event though the private sector activity has been in the doldrums, notwithstanding the boom in residential construction.

The period since 2017 has been dominated by State government major infrastructure projects (the ‘Big Build’ in Victoria and the Connex projects in NSW) and the federal fiscal support during the pandemic.

If you think about the contribution of government, if that fiscal support had not been provided, then the construction sector would have been in much worse shape than it currently is and the economy would certainly have gone into a significant recession during and after the pandemic.

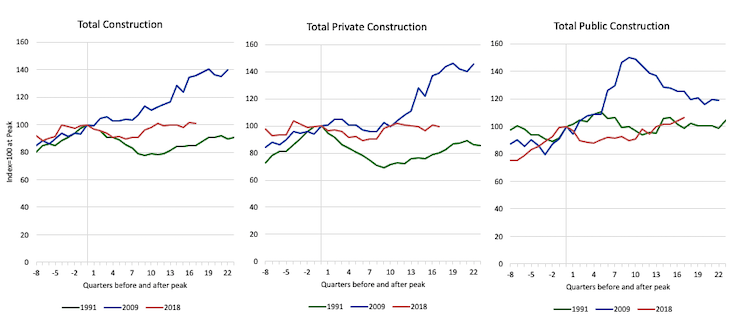

Have a look at these butterfly plots for total construction, public construction and private construction in Australia for the 1991, 2009 and Pandemic downturns.

The butterfly graphs are constructed from the ABS data – Construction Work Done, Australia, Preliminary (published February 22, 2023).

They are construction indexes set at 100 for the peak in activity in the 1991 (September 1989), 2009 (March 2008) and the Pandemic (June 2018) downturns.

They show the 8 quarters before the peak and the 22 quarters after the peak for the 1991 and 2009 recessions and 17 quarters after the peak for the Pandemic episode.

They provide a very good picture of the different fortunes encountered in the construction industry during the respective downturns.

The construction sector historically has been a leading indicator of recession.

It starts slowing down before the rest of the economy catches the pessimism and slumps.

In these three periods shown – the last three major downturns – we see three quite distinct cyclical patterns.

In the 1991 recession, while there was some fiscal support offered to reduce the recessionary impacts it came too late to save the construction industry which contracted sharply.

The Federal government at the time was in denial as to the damage its surplus obsession would cause coupled with the sky high interest rates that the RBA was enforcing.

The Treasurer at the time (Keating) kept telling us that there would be a ‘soft’ landing.

Obviously the advice he was channelling from the Treasury Department was wrong (as usual) and Australia had the worst recession since the Great Depression of the 1930s.

It was a very bad time for workers and families.

As I noted above – the government fiscal response to the GFC threat and the pandemic threat were substantial even if they were targetted at different parts of the construction sector – public infrastructure during the GFC and private residential construction during the pandemic.

Building company collapses

The problem that is emerging is that the government fiscal spending is starting to abate and at the same time the RBA is hiking interest rates.

The fiscal support to the construction industry is thus drying up and the pipeline is thinning.

This is particularly the case in the residential construction sector where we have seen several major building companies – mostly the large-volume, cookie-cruncher builders – collapse in the last few months.

Just two major companies hit the wall last week leaving thousands of people who had homes being built stranded.

There is a combination of reasons for that situation.

1. Fixed price building contracts in an inflationary environment. Fixed price contracts were legislated to protect buyers from unscrupulous builders and provide surety to home lenders (banks) against the dangers of so-called ‘cost-plus contracts’.

The fixed-price contracts work within an environment where construction companies bid hard to win contracts and rely on large-volume activity on low margins per house to survive.

When that activity starts to receded and costs rise, then the builders are vulnerable.

2. Pandemic problems such as sickness of trades workers, supply of materials, etc. created a massive labour shortage in the building industry, which also relied on foreign labour that was shut out with the border closures.

3. The labour shortage has been exacerbated by the big state government construction projects which have attracted constructions workers away from the private sector.

4. Bushfires in 2019 which destroyed forests that supply timber.

5. The war in Ukraine also forced the price of many building materials up – wood, glass products, cement, etc.

Most of these factors would have been manageable (possibly) if the building approvals for new homes didn’t fall off the cliff after March 2021, when two things happened.

First, the Federal governments – HomeBuilder stimulus package – effectively ended.

The program was massive and pushed the demand for homes up (and prices) a bit in an already supply-side constrained environment.

But there is no doubt that it protected the construction sector.

Second, the RBA rate hikes began in May 2022.

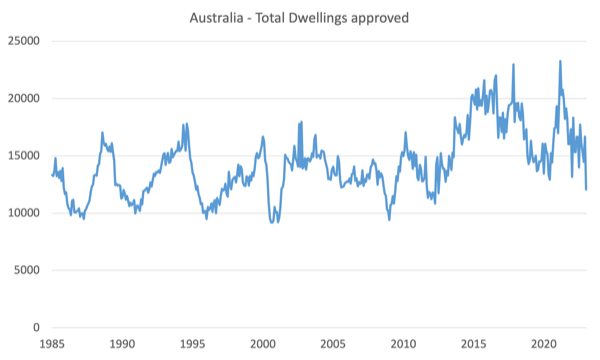

The inflow into the residential construction industry each year is highly variable as the next graph shows (this includes houses and other dwellings, such as townhouses and apartments).

The data runs from January 1995 to January 2023.

The combination of fiscal stimulus programs and low interest rates following the GFC led to a surge in home building.

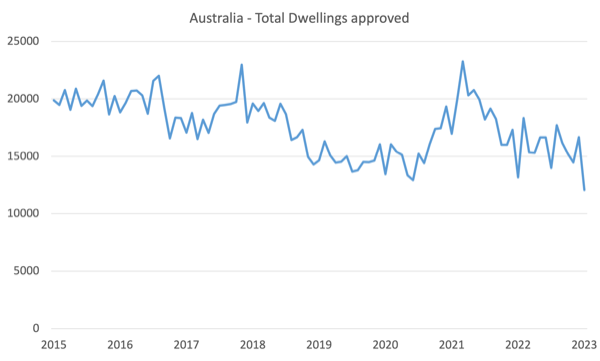

The next graph zooms into the period post January 2015 to January 2023.

The sector was already in decline period to the pandemic after reaching a peak around 2016.

The introduction of the HomeBuilder program in 2020 saw a surge in Total Dwellings Approved but that targetted stimulus was withdrawn and the surge ended.

The acceleration in the decline in 2022 came after the RBA started hiking interest rates.

In April 2022, the total value of building approvals was $A6,271,264 thousand.

By January 2023, that figure had dropped to $A5,587,885, a decline of 10.8 per cent.

In volume terms the decline over the same period has been 21.2 per cent.

So almost a fifth of the demand for new dwellings has gone over the last 9 months.

The prognosis

I have regularly indicated that monetary policy is not an effective tool to deploy when seeking to stabilise the economy.

The impacts are too uncertain – the net impact of the income effects of interest rates on winners and losers is difficult to assess, and in the early stages of the hiking, the rate rises are probably inflationary as they impact on business costs.

At present, central banks that have been hiking rates upwards are deliberately engineering one of the larger income redistributions in history – from low-income (usually poor) to high-income (usually rich).

The problem also is that, ultimately, if monetary policy is to ‘work’ on reducing overall spending, it has to create unemployment and drive businesses broke, particularly construction industry employment and activity.

The related problem is that if the government (and central banks are part of the government structure even though all this ‘independence’ hoopla suggests otherwise) is going to deliberately push people out of work then one would hope they would be able to calibrate the impact very accurately to minimise that damage.

But the central bankers have little idea of the timing and magnitude of the outcomes of their policy changes.

It is such a crude policy instrument that often tens of thousands are rendered without work before the central banks realise they have gone to far.

And more to the point, the logic of monetary policy is only relevant (if at all) to situations where demand is clearly the culprit in driving inflationary pressures and the task is to attenuate the demand back to the ‘full employment’ supply level.

In the current circumstances, even that condition is lacking.

Productive supply capacity fell sharply during the pandemic and is slowly adjusting back upwards as capacity utilisation increases.

The inflationary pressures were never really an excess demand situation.

History tells us though that interest rate hikes eventually start to tilt the economy towards recession – even if small interest rate changes are relatively ineffective.

This is especially so in an environment where fiscal support is being withdrawn.

And as we have seen, in Australia the fiscal support has played a crucial role in sustaining the construction sector,

Interest rate hikes eventually do start undermining activity and that happens in a number of ways:

1. The direct impact on the construction sector as shown above.

2. The impact on general consumption especially within the cohorts that have limited income and large mortgages.

For a time, households can sustain consumption expenditure by running down savings and/or increasing borrowing.

But that is a finite capacity.

Many Australian households borrowed far too much relative to their incomes in the recent boom.

In part, this was because the RBA promised them that they would not face higher interest rates until 2024.

The RBA clearly has reneged on that ‘holding out’ to house buyers but the rising rates are not really the problem.

The problem is that people had too much credit pushed onto them by the greedy banks.

Any slight shift in external environment – hours of work, job availability, cost of mortgages, etc – would be destabilising in an environment where households borrowed more than they could really afford to service.

How do we know that things are tightening other than the major housing company collapses?

Last week, the Australian Securities and Investment Commission (ASIC) released the latest – Australian Insolvency Statistics – which cast a grim cloud over the economy.

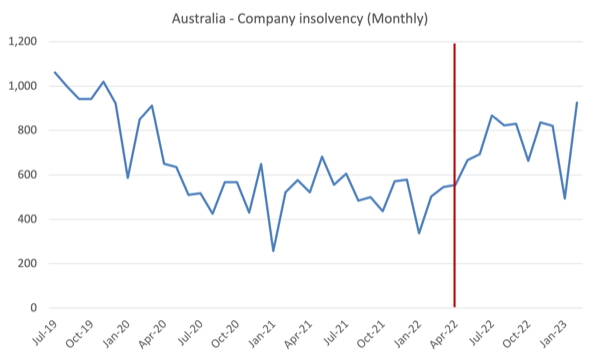

The following graph shows the insolvencies for Australian companies from July 2019 to February 2023 using monthly data.

The vertical red line is the start of the current RBA interest rate cycle.

At the start of the hiking cycle, there were 555 insolvencies and by February 2023, there were 926 reported. The January result is an anomaly due to the extended summer holiday period – where insolvencies are always much lower.

Conclusion

Even if the RBA stops increasing the interest rates, it is likely that several more building companies will go to the wall and the overall economy will head towards recession.

At the same time, the inflationary pressures are easing quickly not because of this deliberate sabotage of employment and industry but because the supply-side factors that were driving them are abating.

Those factors are not interest-rate sensitive.

So you have to wonder what the RBA was thinking about.

The answer is Groupthink – they just have a single-minded focus and were unable to adapt to a situation that was outside that focus.

The upshot is that many thousands of workers will be made unemployed, construction companies will go to the wall, and thousands of families who had contracts with those companies (and paid variable amounts to them) will be left high and dry.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2023 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.