Knowing a true number of residents is crucial to set

development goals – for local government and foreign partners.

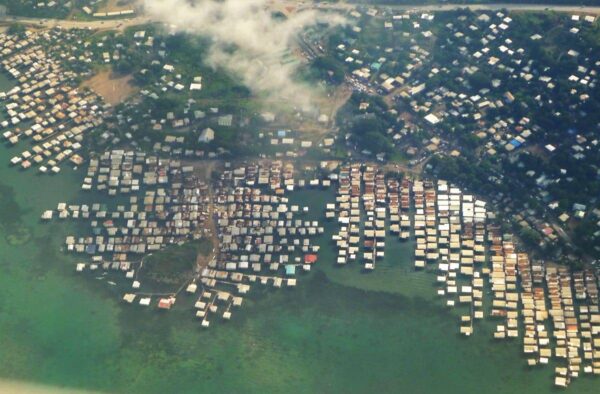

Nobody really knows the size of Papua New Guinea’s population. In December last year, a furore erupted over a 17 million estimate from a supressed United Nations report leaked to The Australian newspaper. PNG’s official population estimate varies between 9 and 11 million for 2022.

The PNG government’s “gag order” on the study, which is yet to be released in full, makes it difficult to assess the veracity of the findings and the methodology employed. The UN study purportedly used satellite modelling, housing data and household surveys. There are reasons then to doubt such estimates, given satellite modelling doesn’t work well in a country where 92 of its 96 districts are rural. Further, household assumptions would likely be inaccurate if they were derived from the census in 2011, which was considered unreliable.

Regardless of the questions raised about the UN study, the controversy showed the importance of obtaining an accurate count of the number of people in the country. Everything from health indicators to service delivery, measures of education levels and more can only be meaningful with a reliable population figure to calculate against – and much larger population estimate would make already poor average living standards appear worse.

Any estimates are bound to be contested. What’s needed is for PNG to run a credible census.

The last census in PNG that was considered credible took place more than two decades ago, in 2000, reporting a population of 5,190,786 people. Projections based on the UN findings would mean an assumed population growth of 5.5 per cent annually in the years since, which is further reason to doubt the claim. The disputed 2011 census results assumed 3.1 per cent annual growth to 2022.

The government has much to gain from clarifying the true population figure via a properly conducted census. For argument’s sake, if PNG’s population was revised upward to 17 million as the UN report was said to have found, PNG would fall from being a lower-middle income country to the low-income category. The ratio of doctors to the population would also fall, as would the proportion of police to population (licensed security guards already outnumber police officers four to one), as would Covid-19 vaccination rates, currently said to be a paltry 3.3 per cent of the population regardless.

Population information has implications for other functions of government, too. Instead of waiting for a credible census, the government last year used the unreliable 2011 census in a redistricting exercise, creating seven new districts in 2022 and proposing six new districts for 2027. According to law, district populations are allowed to vary up to 20 per cent around the average for all districts. In an earlier study using the 2011 census, I found that of the 89 initial districts, 21 had grown too large, and 32 districts had become too small, and even after the splitting, some remain too large or should not have been divided at all.

Uncertain population estimates and indicators, and an inadequate redistricting exercise, all point to an urgent need for a census.

Thankfully, PNG is planning to conduct a census in 2024, and has allocated K50 million (A$20.1 million) for preparations over the coming year. International partners, including Australia, also have a stake in ensuring this exercise is as accurate as possible and applies the lessons from past failures.

The 2011 count failed in part because senior National Statistics Office (NSO) workers at the time were not trained or experienced in conducting a census. Also, the 2011 census lacked a proper listing of households, so logistics and planning for staff was not sufficient.

The 2024 census will face the same logistical challenges, including difficult geography and remoteness, severe weather conditions, and poor telecommunications network coverage.

The NSO may still not be capable of conducting a credible population count. The World Bank’s 2020 Statistical Capacity Indicator scored PNG at 52.2, well below the low- and middle-income country average of 64.9. Further, the NSO’s 2021 reform strategy stated that a lack of government funding had contributed to the loss of skilled personnel.

It isn’t all gloomy. The NSO can draw on the success of the recently completed Demographic and Health Survey (DHS 2016–2018), funded by USAID and conducted with the Department of Health, other PNG agencies, Australia’s aid program, the DHS program, UNFPA and UNICEF. Although it suffered some issues, including taking longer than usual, the 2018 DHS was an achievement as a large, nationally representative survey.

The 2024 census will face the same logistical challenges: difficult geography and remoteness, severe weather conditions, refusal by respondents to participate, challenges to ensure safety of staff, poor telecommunications network coverage, and delays in funds and payments to service providers. International partners should look for opportunities to help local officials overcome these hurdles.

All said, PNG needs to conduct a census, and one that is credible. PNG, however, cannot do this alone. There is scope for optimism that PNG, with assistance, can deliver a credible census, as it did in 2018 with the DHS. It is important, however, that PNG’s development partners take note and prepare to assist come 2024, to avoid another failed census.

This article first appeared in The Interpreter, published by the Lowy Institute.