In my 2015 book – Eurozone Dystopia: Groupthink and Denial on a Grand Scale (published May 2015) – I traced in considerable detail the events and views that led to the creation of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU, aka the Eurozone) once the Treaty of Maastricht was pushed through as the most advanced form of neoliberalism at that time. The difference between the EMU and other nations who have adopted neoliberal policies is that in the former case the ideology is embedded in the treaties, that is, in the constitutional system, which is almost impossible to change in any progressive way. In the latter case, voters can get rid of the ideology by voting the party that propagates it out of office. It is true that in current period, even the parties in the social democratic tradition have become neoliberal and there is little choice. But the EMU is different and has entrenched the most destructive ideology in its legal structures. We are reminded of this recently (April 26, 2023), when the European Commission released its latest missive – Commission proposes new economic governance rules fit for the future. Once operational, the policies advocated in this new governance structure will ensure that Europeans are once again made to endure persistent and elevated levels of unemployment and continued deterioration in the quality and scope of public infrastructure and welfare provision. The collapse of this ideological nightmare cannot come soon enough.

.

Unemployment relativities

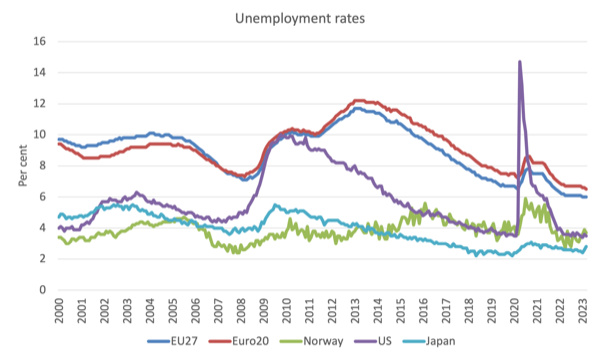

To set the scene, here are some unemployment rates – EU27, Euro20, Norway (a European nation with a currency of its own not pegged to euro), US, and Japan – from January 2000 (the inception of the common currency) to March 2023.

Immediately, you see the problem.

Since the adoption of the euro and for the other 7 EU nations the treaties that support the euro, European unemployment rates have been well above those of the other nations.

Even when the US has experienced a cyclical downturn – 2008 GFC and the pandemic – its unemployment rate resolves back to trend fairly quickly.

Consider the GFC.

The European and US unemployment rates both rose sharply to around 10 per cent.

The US government enacted fiscal stimulus measures and ended the crisis.

In the first quarters of the GFC, the European Member States also engaged in fiscal stimulus and ou can see the unemployment rates peaked and began to fall again in early 2011.

Enter the European Commission and its Excessive Deficit Mechanism and as soon as the austerity was imposed on the Member States the recovery stalled, reversed and for another 3 years unemployment rose again.

And after 10 or so years, the rates have only just come down below what they were prior to the GFC.

Clearly Japan stands out.

It runs a zero interest rate with massive public bond-buying program monetary policy, a yield curve control program (to ensure government bond yields remain below 0.25 per cent), and does not impose restrictive fiscal rules on its policy settings.

And you see the result.

The other point to consider – is if the European unemployment rates are now below what they were just prior to the GFC then how might we explain that?

Well, the reason is two-fold:

1. The ECB has been violating in my view the spirit of the treaties by ignoring the no-bailout clauses and effectively funding the government deficits through their large-scale bond-buying programs.

This has taken the Member State fiscal policies out of the power of the private bond markets and allowed fiscal deficits to rise (albeit somewhat).

2. The suspension of the Stability and Growth Pact at the onset of the pandemic meant that Member States could run larger than usual fiscal deficits and support their domestic economies more fully.

Even with a free reign supported by the ECB, most Member States have not taken full advantage of the relaxation, in part, because they probably feared the adjustment back to austerity would be harder once the European Commission reinstated the Excessive Deficit mechanism under the fiscal rules.

Taken together, unemployment rates, while still excessive, have fallen to their lowest level since the common currency was introduced at the turn of the century.

It just goes to show.

The current fiscal situation in EMU

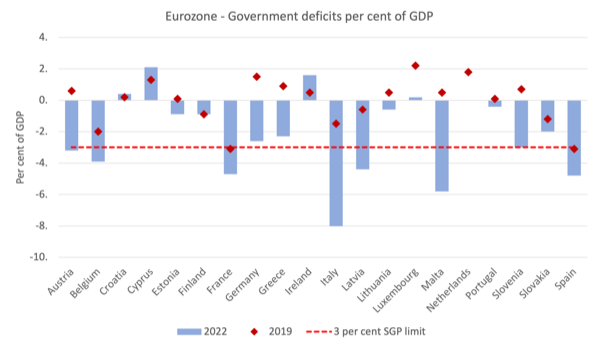

The following graph shows the current state of fiscal balances (as a per cent of GDP) in the Eurozone Member States for 2019 and 2022.

The red diamond markers depict the pre-pandemic situation, while the blue columns depict the 2022 results from Eurostat.

The red horizontal line is the 3 per cent Stability and Growth Pact allowable limit for fiscal deficits.

We don’t get data into 2023 yet from Eurostat.

After the long period of austerity post GFC, by 2019 on 2 Member States remained in violation of the Stability and Growth Pact rules (France and Spain).

After the fiscal policies to deal with the pandemic there were now 7 Member States in violation by the end of 2022.

I think that figure will increase as we get more data for the first months of 2023 and as GDP growth continues to slow.

For nations such as France, Italy, Malta and Spain any thought of getting back inside the 3 per cent threshold any time soon, especially as there are threats of recession looming (with ECB hiking rates and reducing its public bond purchases), would be disastrous for the well-being of their citizens.

The French are already in revolt.

That will worsen and spread.

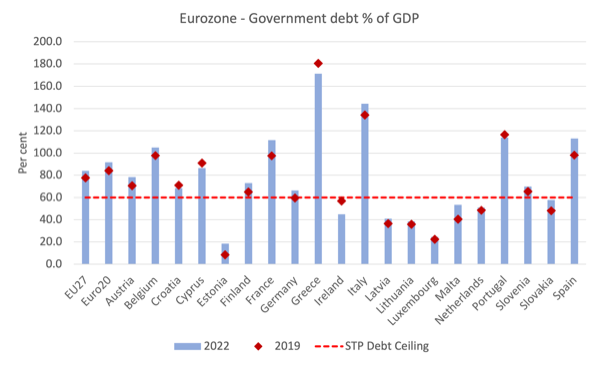

What about the public debt situation?

The following graph shows the current state of public debt (as a per cent of GDP) in the Eurozone and for the EU27 overall for 2019 and 2022.

The red diamond markers depict the pre-pandemic situation, while the blue columns depict the 2022 results from Eurostat.

The red horizontal line is the 60 per cent Stability and Growth Pact allowable limit.

Prior to the pandemic, 11 of the 20 EMU Member States were in violation of the fiscal rules with four more close to violation.

By the end of 2022, that number had increased to 12.

Between 2019 and 2022, public debt ratios had increased in 16 of the 20 Member States.

Of the nations that were already in violation in 2019 (11), public debt ratios increased between 2019 and 2022 in 8 of them.

Several nations (7) have debt ratios above 80 per cent, while 6 have debt ratios above 100 per cent.

In other words, to get back in line with the fiscal rules will be nearly impossible without extensive and extended austerity.

Whether the social fabric of those nations would allow such adjustment is questionable.

Unlikely, is my assessment.

The oppression is about to resume

As I noted above, the fact that unemployment (albeit still very high) is levels not seen in the history of the common currency, is in part due to the relaxation of the fiscal rules, which have given nations more latitude.

16 of the 20 Member States expanded their fiscal deficits between 2019 to 2020 although given the unemployment rates are fairly high still, they could have expanded more.

A fairly cursory statistical analysis shows that the nations that expanded the most enjoyed the largest falls in their official unemployment rates.

I will publish that in due course when I have more time to do deeper analysis with proper controls for endogeneity.

So given all that, why one earth would the European Commission seek to reassert the fiscal rules which will definitely cause unemployment to rise and poverty rates to rise?

For that is what they announced on April 26, 2023 in the statement cited in the introduction.

They claim the new “legislative proposals” will be the “the most comprehensive reform of the EU’s economic governance rules since the aftermath of the economic and financial crisis.”

The usual narrative is used as justification – “strengthen public debt sustainability and promote sustainable and inclusive growth.”

The European Commission are masters at using language that sounds as though it will be of benefit to greater population when in fact the very opposite is the case.

The Commission claims the:

The proposals address shortcomings in the current framework. They take into account the need to reduce much-increased public debt levels, build on the lessons learned from the EU policy response to the COVID-19 crisis and prepare the EU for future challenges by supporting progress towards a green, digital, inclusive and resilient economy and making the EU more competitive.

Then we cut to the chase:

National medium-term fiscal-structural plans are the cornerstone of the Commission’s proposals.

In other words, the Member States will have to be guided by the Commission as to their fiscal policy proposals.

And they will have to “integrate … fiscal, reform” targets and be monitored annually by the Commission.

So expect to see more welfare cuts, privatisations, outsourcing, pension cuts, wage constraints – which all come under the moniker of ‘reform’.

Reform sounds like progress.

Except in the EU it means pernicious attacks on the welfare of the working class.

More specifically, this so-called increased “national ownership” of fiscal trajectories must be conducted within the reinstated fiscal rules set by the Commission.

The Commission states:

For each Member State with a government deficit above 3% of GDP or public debt above 60% of GDP, the Commission will issue a country-specific “technical trajectory” …

For Member States with a government deficit below 3% of GDP and public debt below 60% of GDP, the Commission will provide technical information to Member States to ensure that the government deficit is maintained below the 3% of GDP reference value also over the medium term.

In other words, if a Member State is in violation of the Stability and Growth Pact thresholds, the Commission will enforce (the so-called ‘technical trajectory’) austerity to make the Member State move towards the thresholds.

How much time will a nation have?

Well not much:

The ratio of public debt to GDP will have to be lower at the end of the period covered by the plan than at the start of that period; and a minimum fiscal adjustment of 0.5% of GDP per year as a benchmark will have to be implemented so long as the deficit remains above 3% of GDP.

And the adjustment must be immediate (“not postponed to the outer years”).

So take Italy which currently has a fiscal deficit of 8 per cent of GDP.

It will have to contract its fiscal settings by at least 0.5 per cent of GDP.

I did some calculations using Eurostat’s latest data that show that while real GDP grew in the final quarter 2022, a 0.5 per cent withdrawal of net expenditure as part of an austerity program would push the economy into recession immediately.

Conclusion

I will do some more work on the ‘technical trajectory’ concept.

But it is just another fancy term for austerity.

The type that prolonged the elevated unemployment rates after the GFC.

We learn from this that while the people might think lower unemployment is a good thing for them – they have incomes, can risk manage, etc – the same doesn’t hold for the technocrats in Brussels.

They are on an ideological crusade to reassert their authority and they know full well that hundreds of thousands of Europeans will lose their jobs as a result of imposing these ‘technical trajectories’.

But their purpose will be realised.

At least until the social instability brings the whole rotten system down.

That cannot come soon enough.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2023 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.