As the inflation episode starts to abate, central bank governors have been keen to advance narratives to justify why they would continue hiking interest rates, especially when it is pretty obvious that the drivers of the inflation were mostly coming from the supply-side and suppressing aggregate spending (via the higher rates) would not be a very effective measure to deploy. This is quite apart from the debate as to the effectiveness of using interest rates to stifle spending, which is a separate discussion with no clear conclusion other than probably not. As I have noted previously, it was hard to argue that inflation was accelerating out of control when it had started to decline many months ago. So they had to come up with a different narrative – which was that while inflation was falling it was not falling quickly enough. That is the current story line the officials trot out. And that allows them to claim that if it doesn’t fall quickly then two things will be likely: (a) workers will build the higher inflation into their wage demands and set off a wage-price spiral that becomes self-fulfilling even after the supply-side factors (Covid, Ukraine, OPEC) abate, and (b) that people would start to expect higher inflation was the norm and build that into the contractual arrangements and pricing. Neither behavioural phenomenon has shown any sign of becoming entrenched, which leaves the central bank officials without a cover. And even research from central banks themselves is demonstrating that there is not ‘high inflation’ mindset taking over.

Wages growth is not inflationary

On Tuesday (May 30, 2023), the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco released their latest ‘Economic Letter’ – How Much Do Labor Costs Drive Inflation? – which addresses the wage question.

The research is motivated by statements made by the Federal Reserve Chair in 2022 that wage movements were driving movements in “nonhousing services” given they are “the largest cost in delivering those services”.

His assertion has been repeated regularly in a number of different ways by central bank governors and senior officials around the world since the middle of 2021, when increasing inflationary pressures started to emerge.

The FRBSF researcher noted that “nonhousing services are an important component of overall inflation, making up over half of the core personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index.”

Further, “Worker wages and benefits make up the bulk of costs to firms” who supply these non-housing services.

Previous research has demonstrated that “labor costs have little impact on services inflation or inflation overall” because firms can always “absorb such costs into their profit margins” and, sometimes, reorganise the work place to gain productivity boosts, which offset the higher wage costs.

The FRBSF paper framed the study by considering that:

… increases in labor costs act like supply shocks, whereby businesses pass on higher costs to consumers in the form of higher prices. By contrast, labor cost growth does not appear to fuel inflation through higher demand.

This is an important distinction because it suggests that the higher incomes that workers enjoy as a result of wage increases do not lead to excess demand situations for goods and services.

Often opponents to wage rises in the corporate sector try to claim that rises will be inflationary because they will put pressure on spending.

The FRBSF paper rejects that assertion outright.

In relation to the other pathway – the higher unit costs/supply effect – the research shows that:

… the effect is small and occurs slowly over a long time. A 1 percentage point (pp) increase in labor costs causes only a 0.15pp rise in the contribution of NHS prices to core PCE inflation over a four-year horizon, which is less than 0.04pp per year. This implies that the recent run-up in the employment cost index (ECI) is contributing only about 0.1pp to current core PCE inflation, stemming entirely from the impact on NHS inflation.

In other words, very small second-order type effects and not a basis for building a narrative that interest rate rises are justified to prevent a wage-price spiral breaking out.

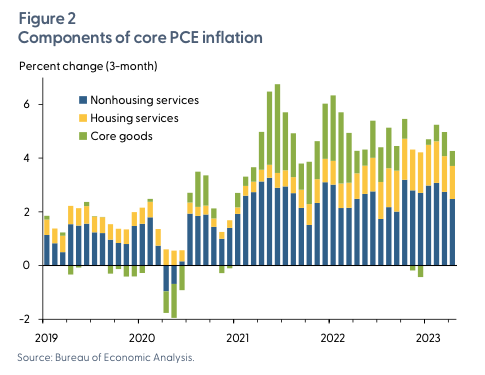

To further the argument, the FRBSF paper produced Figure 2 (reproduced here), which shows the components of the Core PCE Inflation measure published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics since 2019.

These components are nonhousing services, goods and core goods and the graph shows that Core goods inflation “rose dramatically” in 2021 but has declined sharply since.

I noted in blog posts last year that this impact was easily understood in the context of the pandemic and the way that governments dealt with the threat.

Not only was the supply chain of goods severely disrupted by sickness and factory and transport closures but governments also restricted access to service sector activities while at the same time providing fairly extensive income support to workers affected.

With incomes protected to some extent and no capacity to engage in service related spending, it was obvious that the diverted spending on goods – home improvements, brought forward purchases, etc – would push up prices of those commodities especially as they were in relatively short supply in 2020 and 2021.

To call that an excess demand inflation is true in a strict sense but from a policy perspective such a diagnose has led to destructive policies from central banks and treasuries.

It was clear that the overall spending did not grow that much and that the problem was the ‘temporary’ reduction in supply capability.

So it was better taking the Japanese route and waiting for the supply side to resolve while at the same time protecting the most disadvantaged households from the temporary cost-of-living stress with fiscal injections.

Using macroeconomic policy to kill off spending would just leave a legacy of higher unemployment and lost incomes as the supply side overcome its constrained environment.

The graph shows how that part of the story resolved itself mostly by the middle of 2022.

Conversely, nonhousing services as increased its contribution and maintained the level over the course of the inflation cycle.

The FRBSF paper calculates that:

NHS is contributing 2.4pp to three-month core inflation, which is 1pp larger than its 2016–19 average contribution.

And because nominal wages growth has increased over this period – chasing the CPI movements – many commentators are blaming that movement on the overall PCE movement.

The FRBSF research examines the relationship between movements in the Employment Cost Index (ECI), the best measure of labour costs and NHS inflation over the period 1988 to 2023, using quarterly data.

So it uses sufficient data observations to estimate a robust econometric model and gain sound inference.

Interestingly (from an econometrics perspective), they find no significant difference in the relationship when they split the sample into two at around 2020.

So the relationship in the current period behaves similarly to the pre-pandemic period, despite the extraordinary nature of the pandemic.

The first results they report are:

1. The impact of ECI increases on Goods and Housing Services inflation is negligible and not statistically different from zero.

2. The impact on NHS is positive and statistically significant but “the magnitude is quite small”.

3. “As ECI growth has increased by about 3pp from its pre- pandemic level, this means that labor costs have added approximately 0.1pp to current core PCE inflation.”

So really nothing to see here!

The other issue they explored was whether this minuscule wages effect worked via the supply-side (pushing up costs which firms pass on) or demand-side (higher spending effect), which I mentioned above.

The research concludes that:

The ECI has no discernible effect on the demand-driven component of NHS inflation. Instead, the impact of ECI growth on NHS inflation stems entirely from the supply-driven component. Thus, this result indicates that increases in labor costs act like typical supply shocks, whereby businesses pass higher costs along to consumers in the form of higher prices.

But as noted previously, this effect is small.

Importantly, they note that:

… recent evidence shows that wage growth tends to follow inflation … [and] … that recent labor-cost growth is likely to be a poor gauge of risks to the inflation outlook.

This is significant research.

I have noted in the past that when you observe real wages declining it is hard to mount a case that wages are driving inflation.

The FRBSF research supports that claim – that nominal wages growth is chasing the inflation but not catching up or overtaking it.

Which then leaves us to suggest that the inflation now, as those Core Goods supply pressures are abating fast, is being driven by margin push – the so-called ‘greedflation’.

That now stands as a highly plausible explanation for the ‘persistent’ of the inflationary pressures into 2023.

RBA governor still blames wages

Yesterday, the RBA governor appeared before the Commonwealth Senate Estimates Committee.

The transcript is still not available.

But we have a good set of quotes from his appearance.

He claimed that real wages have to continue falling in Australia in order for inflation to get back to the RBA’s target range of 2 to 3 per cent because productivity growth had stalled.

In other words, he was in not so many words, suggesting that the RBA would deliberately drive the economy into recession in order to achieve further declines in real wages.

In the March-quarter 2019, the real wage index (derived from the ABS Wage Price Index) stood at 113.1, which was the most recent peak.

That indicated that real wages had only growth by 13.1 per cent since the September-quarter 1997, when the WPI data series began.

By comparison, over the same period, GDP per hour of labour input (productivity) had grown by 29.6 per cent, meaning that over this 2 decade or more period, national income had been massively redistributed away from workers to profits

The relevant measure is the wage share and that moved from 55 per cent in the September-quarter 1997 to 50 per cent in the December-quarter 2022.

An unprecedented shift to profits.

That means in plain language that workers real wages have not growth in proportion to productivity growth and the gap has been pocketed by business firms.

In the March-quarter 2023, the real wage index stood at 107.2 points while the productivity index had grown from 129.6 points to 131.8 points.

So real wages have declined over this period (March-quarter 2019 to March-quarter 2023) by 5.1 points and labour productivity has grown by 1.7 points.

Sure enough, the productivity growth has been very low by historical standards.

But still, employers have found ways to exploit the inflationary period to suppress real wages yet still pocket gains from labour productivity via elevated profit margins.

So when the RBA governor claims that the only way real wages can rise is through productivity growth, he is not telling us the full story.

Even with the parlous productivity growth the Australian economy is producing at present, there is scope for non-inflationary real wage increases if we force the corporations to desist from profit-gouging.

That is, there is scope to reduce profit margins from their inflated levels that have allowed the profit share to expand.

Conclusion

However, don’t expect the RBA governor to articulate that message any time soon.

As I noted yesterday, the governor mislead the Senate Committee when he claimed the only profit increases have been in the resources sector.

That was obviously not a statement that can be supported by the data.

That is enough for today!