I once worked at a small company of insanely productive engineers. They were geniuses by any account. They knew the software stack from top to bottom, from hardware to operating systems to Javascript, and could pull together in days what would take teams at other companies months to years. Between them they were more productive than any division I’ve ever been in, including FAANG tech companies. In fact, they had written the top-of-the-line specialized compiler in their industry — as a side project. (Their customers believed that they had buildings of engineers laboring on their product, while in reality they had less than 10.)

I was early in my career at the time and stunned by the sheer productivity and brilliance of these engineers. Finally, when I got a moment alone with one of them, I asked him how they had gotten to where they were.

He explained that they had been software engineers together in the intelligence units of their country’s military together. Their military intelligence computers hadn’t been connected to the internet, and if they wanted to look something up online, they had to walk to a different building across campus. Looking something up online on StackOverflow was a major operation. So they ended up reading reference manuals and writing down or memorizing the answers to their questions because they couldn’t look up information very easily. Over time, the knowledge accumulated.

Memorization means purposely learning something so that you remember it with muscle memory; that is, you know the information without needing to look it up.

Every educator knows that memorization is passé in today’s day and age. Facts are so effortlessly accessible with modern technology and the internet that it’s understanding how to analyze them that’s important. Names, places, dates, and other kinds of trivia don’t matter, so much as the ability to logically reason about them. Today anything can be easily looked up.

But as I’ve gotten older I’ve started to understand that memorization is important, much more than we give it credit for. Knowledge is at our fingertips and we can look anything up, but it’s knowing what knowledge is available and how to integrate it into our existing knowledge base that’s important.

- You Can’t Reason Accurately Without Knowledge

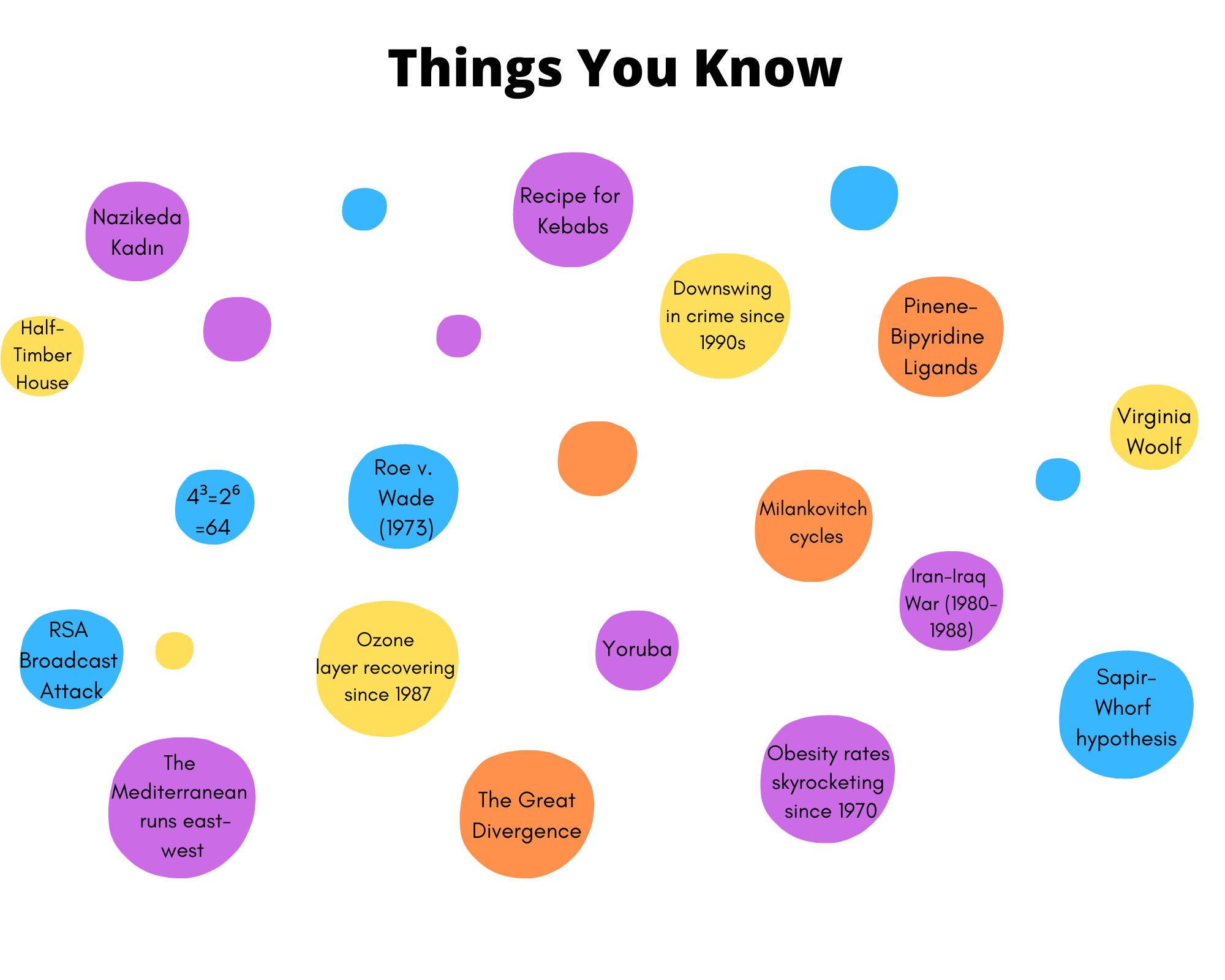

You know a lot of things.

/>

A

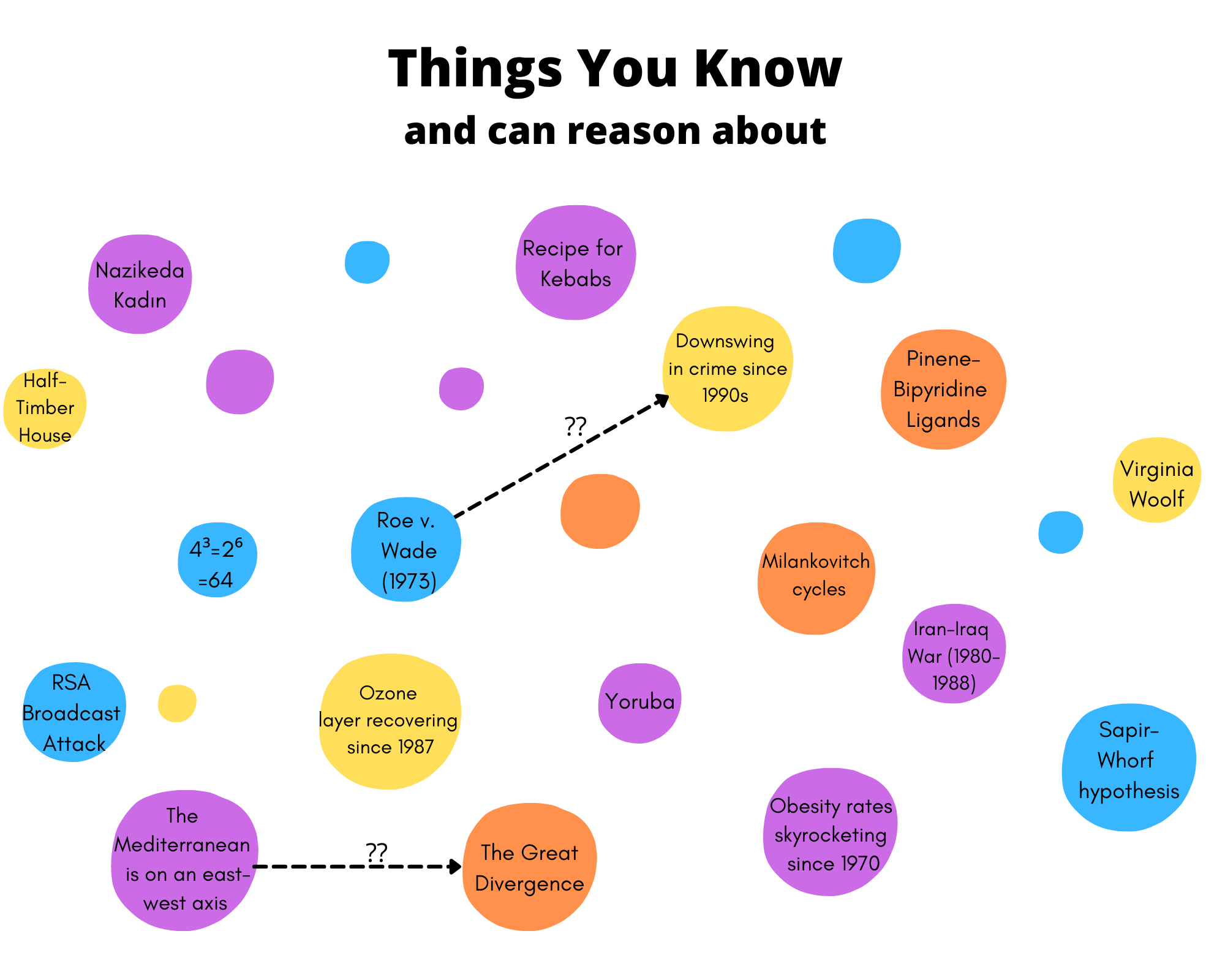

lot of life involves reasoning: taking this information you have and making hypotheses that connect different pieces in a way that provides a deeper understanding of them.

The more information you have muscle memory for, the more you can use to reason about.

But you can’t draw connections between things you don’t know exist, or don’t have a good “feel” for.

The problem with not memorizing is that you’re limited by the lack of data points, or nodes that you can make connections between. In short, you’re limited by your lack of understanding of what to look up.

Here’s a small illustration.

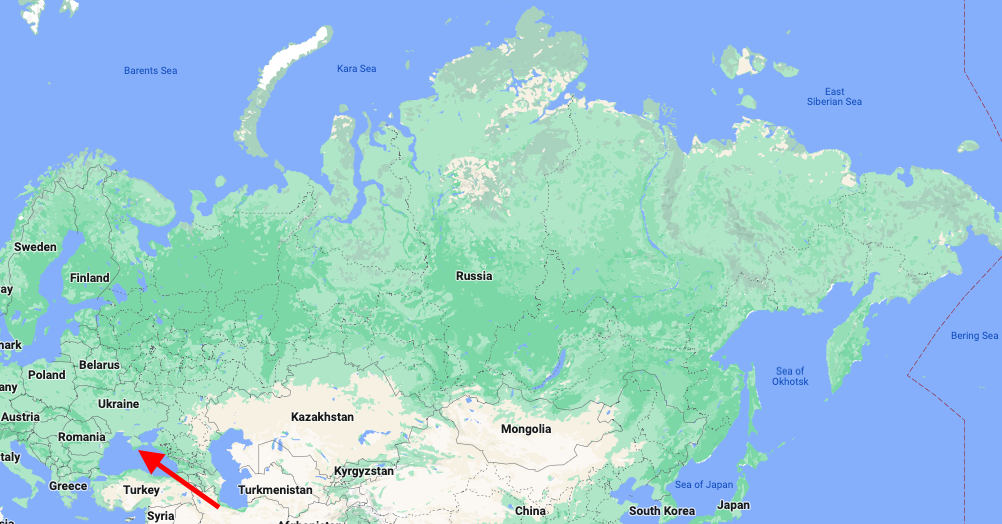

Many would argue that there is no point for kids to memorize the world map today. But if you know basic geography, you will hear all kinds of political analysis that only works because the person arguing it doesn’t have any idea where anything is on a map. This is the problem with not making school kids learn basic geography. You can look up any country on Google, but if you’ve never had to memorize approximately where they are, either voluntarily or in school, you’ll never get a sense of why things are the way they are.

Here are some examples that show how that works.

Why does Oman have so much power in today’s Middle East – enough power that it can stay neutral in the various regional conflicts and still be a dominant political player?

This is why:

Oman controls the Strait of Hormuz, the only water-based entry to the Persian Gulf. Any country that messes with Oman risks being denied access to the Persian Gulf.

A second example: at the time of the writing of this article, Russia was a month into an invasion into Ukraine. This is not the first time in even the decade that Russia has tried to take over its neighbor: in 2014 Russia illegally invaded and annexed Crimea, and is still controlled by Russia today. Why does Russia want to control Crimea so badly? If it’s a power play, why not threaten Belarus or Latvia, which also border Russia and would be easy to take over?

This is why:

Crimea’s Port of Sevastopol is a highly-desired prize for Russia: it gives Russia control over the Black Sea and trade access to the Mediterranean Sea. Russia has only two warm-water ports that don’t freeze during the winter: Vladivostok, which opens to the Pacific, and St. Petersburg, which opens to the Baltic. There are other factors as well, obviously, but Russia’s pursuit of warm-water ports is a frequently recurring theme in its history.

This may seem basic, but many people have never thought to look up these places on a map. If you were trying to just think of the answers you could easily miss them entirely. But if you memorized the map at some point, you knew where those places are and probably could have thought of the answer.

Or try a basic historical example: if you know that the printing press was invented in 1450, you can make the connection between that and the Protestant Reformation in 1517.

The point is that memorizing data gives you a bank of material to run through when forming and testing a hypothesis. When you rely solely on analysis as a form of knowledge-synthesis, you’ll often reach the wrong conclusions simply because you do not have good data to base your deductions on. Of course you can and should research, but you’ll be much more accurate much more quickly when you’ve got the information in your head at hand.

Chances are, you won’t naturally remember all these facts, and that’s where the memorization comes in.

To paraphrase a saying that LessWrong readers will recognize, your map is not the territory. Your job is to add as many features to your map as you can to make it resemble the territory as closely as possible. The more detailed the features on your map, the closer you will be to having an accurate idea of the territory.

- Memorizing Organizes Your Knowledge

You know that feeling when you’ve got a lot of information about something, but it’s all jumbled and confusing and fragmented? You might feel this way about car parts, or historical events. Did the Babylonians come before or after the Persians? Did Frederick William I of Prussia come before or after Frederick I? Or William I?

When you look up every fact you want to know independently of its context, you risk it being jumbled and vague and fuzzy in your head. For example, if you heard that Daylight Savings Time started in 1916, you’d likely quickly forget the date.

But if you have key checkpoints of information memorized, new data has a solid place to lodge itself in your mind. If you know that World War I started in 1914 and ended in 1918, and someone mentions that Daylight Savings Time started in 1916, you’ll quickly deduce that they are related. You’ll also remember the approximate date that Daylight Savings Time began: sometime during World War I.

Imagine you’re an engineering manager. Who would you rather hire: the person who knows exactly what features are available in PHP 7 and which are only available in PHP 8, or the one who will figure it out by trial-and-error of while writing each application and seeing what fails? Of course, the second engineer certainly may produce quality work. But the first one unquestionably has an comprehensively organized framework of the tools he has at his disposal.

Memorizing information gives you a concrete organizational scaffolding and context in which to put new information. Memorizing an organized set of facts means that new information can be inserted in an orderly way, sandwiched or enhancing other facts in an organized framework.

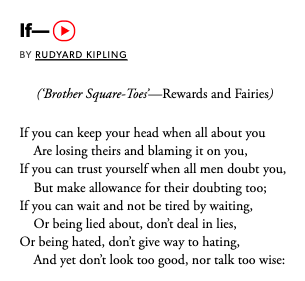

My high school completely eschewed memorization as a way of learning. Because of that, students were outraged when, in tenth grade, an older teacher tried to require the class to memorize the equivalent of about four sentences of poetry for a test. All hell broke loose. Being asked to memorize forty words was slightly less outrageous than being asked to memorize the collected works of William Shakespeare. The students brought articles in proofs they had found online that memorization isn’t a good way to learn, that it would doom us all to a life of lifeless brain-dead chanting of facts, that it would cause all their neurons to flop over and die from the effort. If I remember correctly, they even tried to get parents involved.

But the school stood behind the teacher, and the teacher stood firm, and ultimately we had to be able to repeat back the lines of the poem via a fill-in-the-blank section on the test.

Over the years those lines have come back to me many times, and I understand them on a much deeper level. There’s no way I’d ever look them up, but having them accessible has made my life immeasurably richer.

Subconsciously, when you learn a piece by heart, its message penetrates deep inside you. It lies at your fingertips, ready for you to make use of it. Many cultures have long understood this. In Islam, people who memorize the entire Koran are given the special title of hafiz, or guardian. In a secular equivalent, I know people who have memorized Rudyard Kipling’s poem If— to give them a moral helping hand at times of crisis.

Even if you don’t really understand it the first time, memorizing information and literature gives you the opportunity to come back to it. In the words of a college professor of mine, the point of a liberal arts education is to give you what to think about. Having literature, poetry, or even just quotations at the tip of your fingers makes for a more vivid, vibrant, and resonant life.

Be notified about new articles.