My early academic work was on the Phillips curve and the precision in estimating the concept of a natural rate of unemployment, or the rate of unemployment where inflation stabilises at some level. This rate is now commonly referred to as the Non-Accelerating-Rate-of-Unemployment (NAIRU) and my contribution was one of the first studies to show that the rate was variable and went up and down with the economic cycle, rendering it a meaningless concept for discretionary policy interventions. I extended that work into my PhD and built on much earlier work as a undergraduate to articulate the Job Guarantee idea. The NAIRU is unobservable and there have been various ways to estimate it from actual data. The problem is that these estimates are highly sensitive to the approach – so two researchers can get quite different estimates using the same data. Further, the estimates themselves are subject to large statistical errors meaning that we cannot be sure whether the NAIRU is say 4.5 per cent or 3.5 per cent or 5.5 per cent, say. Such imprecision makes it impossible to use the concept as a guide for monetary policy because if the NAIRU actually existed then ‘full employment’ might be at 3.5 or 5.5 per cent today but next week the estimates might be even wider. When would one want to start changing interest rates in pursuit of inflation stability – when the actual unemployment rate was down to 3.5 per cent or at 5.5 per cent or somewhere in between or at higher or lower unemployment rates, depending on what the models pumped out? You can see the problem. For some years, central bankers went quiet on the use of the NAIRU and stopped publishing their estimates exactly because they knew full well about the imprecision and that policy based on such a vague, difficult to estimate, unobservable would be discredited. That is until now. The RBA is now clearly admitting that their damaging and unnecessary interest rate hikes over the last year and a bit have been driven by the NAIRU. A sham. But a tragedy as well given the RBA’s almost obsession with pushing unemployment up by around 140,000. A shocking indictment of where we have reached as a civilisation.

First to Japan

Every day the Bank of Japan sends me E-mail briefings of the developments in Japan for that day. It is a very valuable source of information.

Yesterday’s briefing included the – Minutes of the Monetary Policy Meeting on April 27 and 28, 2023 – which detailed the discussions at the last Policy Board meeting.

Reading them is like being in a parallel universe when compared to the statements that have been coming out of other central banks, including the latest – Minutes of the Monetary Policy Meeting of the Reserve Bank Board (published June 6, 2023).

We read:

1. “In accordance with the short-term policy interest rate of minus 0.1 percent and the target level of the long-term interest rate, both of which were decided at the previous meeting on March 9 and 10, 2023, the Bank had been conducting purchases of Japanese government bonds (JGBs)” – so they are continuing to use their dominant position in the government bond markets to maintain low interest rates – unmoved by what other central banks are doing.

2. “The Bank will purchase a necessary amount of JGBs without setting an upper limit so that 10-year JGB yields will remain at around zero percent” – they are buying JGBs “every business day” to ensure yields remain at “around 0 per cent”.

3. “the shape of the JGB yield curve had been generally smooth, as interest rates had declined, mainly at medium- to long-term and super-long-term maturities” – thus providing good investment conditions for long-term capital formation. Sensible.

4. “In the money market, interest rates on both overnight and term instruments generally had been in negative territory.”

5. “In the foreign exchange market, the yen had appreciated against the U.S. dollar … Meanwhile, the yen had depreciated against the euro” – so no hard and fast rule that such a monetary and expansionary fiscal stance would drive the yen towards collapse.

6. “Japan’s economy had picked up, despite being affected by factors such as past high commodity prices” – while economic activity around the world declines on the back of the interest rate hikes.

7. “The employment and income situation had improved moderately on the whole.”

8. “In real terms, the year-on-year rate of change in employee income was projected to gradually turn positive toward the middle of fiscal 2023, as inflation declined and nominal employee income improved” – workers of the world unite!

9. “With the impact of past high commodity prices and yen depreciation gradually waning, the rate of change in the producer price index (PPI) relative to three months earlier had started to decline slightly, partly due to the effects of the government’s measures to reduce the burden of higher electricity and gas charges” – so fiscal policy interventions were anti-inflationary.

10. “Inflation expectations were more or less unchanged after rising” – so even though interest rates are unchanged and fiscal policy is expansionary, people are not building the temporary elevated inflation level into their decision making. They realise this is a transient phase and patience is the key.

11. “the year-on-year rate of increase in the CPI (all items less fresh food) was expected to decelerate toward the middle of fiscal 2023, with a waning of the effects of the pass-through to consumer prices of cost increases led by the rise in import prices” – they based their policy decisions on the assumption that the inflationary pressures were transitory and the events are validating that justification. Smarter than the rest.

12. “in order to achieve the price stability target of 2 percent in a sustainable manner, this needed to be accompanied by wage increases … it was necessary for the Bank to continue to firmly support the momentum for wage hikes by maintaining monetary easing so that the nominal wage growth rate would rise sufficiently relative to prices” – which is official government policy to push up wages growth. Parallel universe!

There was much more in the Minutes but this gives you an idea of how far removed from the rest of the central banking narratives, the Bank of Japan is.

Ministry of Finance and the Cabinet Office input into the discussions were supportive of the Bank’s accommodative stance continuing and there were statements affirming the Cabinet Office’s intention to swiftly implement the latest fiscal expansionary measures.

A parallel universe indeed.

Past central bank scepticism

Here some quotes I dug out from my database this morning.

The first was from an address on November 29, 1994 – Inflation, Current Account Deficits and Unemployment – that the then RBA Governor Bernie Fraser gave to CEDA in Melbourne, which was subsequently published in the December 1994 edition of the RBA Bulletin:

This has led to the notion of a ‘natural’ rate of unemployment, or what economists have called the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment, or the NAIRU – either way, a terrible mouthful. In simple terms, it is a minimum unemployment rate below which the economy cannot operate for any sustained period without generating wage pressures and pushing up inflation. No-one knows precisely what this minimum rate is, but different researchers have suggested a range of 6 to 8 per cent for Australia, with most estimates towards the top of this range. Estimates for some European countries tend to be higher still, at 8 to 9 per cent; for the United States, it is generally thought to be around 6 per cent.

It is a fuzzy concept and of limited practical value.

The fast track to the August 24, 2018 speech that the Federal Reserve Bank boss Jerome Powell gave at the Jackson Hole Symposium – Monetary Policy in a Changing Economy:

With the unemployment rate well below estimates of its longer-term normal level, why isn’t the FOMC tightening monetary policy more sharply to head off overheating and inflation? …

In conventional models of the economy, major economic quantities such as inflation, unemployment, and the growth rate of gross domestic product (GDP) fluctuate around values that are considered “normal,” or “natural,” or “desired.” …

These fundamental structural features of the economy are also known by more familiar names such as the “natural rate of unemployment” and “potential output growth.” … At the Fed and elsewhere, analysts talk about these values so often that they have acquired shorthand names. For example, u* (pronounced “u star”) is the natural rate of unemployment … According to the conventional thinking, policymakers should navigate by these stars. In that sense, they are very much akin to celestial stars …

if the unemployment rate is above u*, lower the real federal funds rate relative to r*, which will stimulate spending and raise employment.

Navigating by the stars can sound straightforward. Guiding policy by the stars in practice, however, has been quite challenging of late because our best assessments of the location of the stars have been changing significantly.

And then a year later (August 25, 2019), at the Jackson Hole again, the RBA governor Philip Lowe’s – Remarks at Jackson Hole Symposium – invoked the ‘shifting stars’ in his speech:

Over recent times there have been very large shifts in estimates of full employment (U star) …

These shifts have occurred not just in one or two countries, but they have occurred almost everywhere. The fact that the experience is so common across countries strongly suggests there are some global factors at work.

It is worth noting that these shifts in the stars were not predicted – they have come as a surprise … the reality is that our understanding is still far from complete about what constitutes full employment in our economies and how the equilibrium interest rate is going to move in the future.

Which all goes to show that the central bank bosses know full well that the NAIRU is not a reliable basis for more precise policy changes.

Economists do not know when the estimates of the NAIRU will shift nor what causes them to shift.

I have documented previously the deep uncertainty in the estimates provided by central banks – see the extensive Background Reading list at the end of this blog post.

On June 12, 2019, the Assistant RBA Governor gave a speech in Melbourne – Watching the Invisibles – where she talked about the NAIRU.

She said that in inferring some number for the NAIRU (an unobservable) from other visible variables, one is “asserting that a particular theory, a particular model of how the world works, is true.”

If the theory is unsustainable, then the inference will be useless.

She asserted, though that the theory has credence that:

… there is a level of unemployment below which wages growth starts to pick up meaningfully. You can see when an economy has reached that point. That is all that the NAIRU is – the label we give to that point.

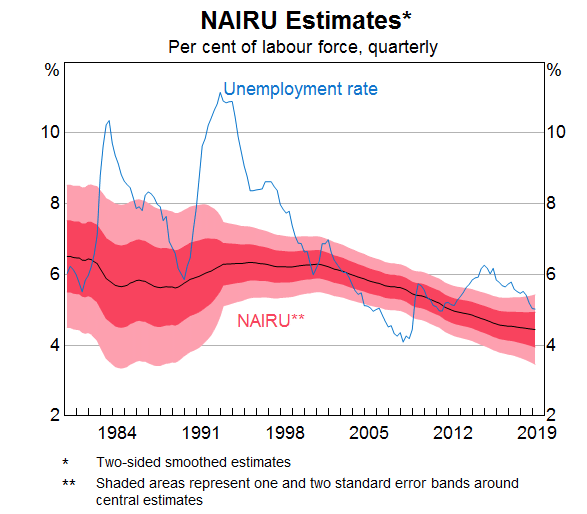

She also published the, then, latest RBA estimates of the NAIRU which is depicted in this graph:

She notes in relation to the graph that:

There is substantial uncertainty around our estimate of the NAIRU. First, there is uncertainty around the estimate of the NAIRU even when assuming this model of the relationship between wages, inflation and the unemployment gap is the best model. This is because even with the best choice of statistical approach, it is difficult to be precise about that relationship. The model estimates that there is a two-thirds chance that the current NAIRU is between 4 and 5 per cent, and a 95 per cent chance it is between 3½ and 5½ per cent …

For the non-statisticians reading this, the relevant phrase is “a 95 per cent chance it is between 3½ and 5½ per cent”.

What that means is that the RBA has no way of differentiating using this sort of methodology between a NAIRU of 3.5 per cent and a NAIRU of 5.5 per cent, which is the point I made earlier.

A 2 per cent range is too imprecise for policy decisions when they are manipulating interest rates 0.25 basis points at a time.

At present, the Australian unemployment rate is 3.55 per cent, yet the RBA is claiming the NAIRU is 4.5 per cent (which is the ‘point estimate’ from their modelling) around which those confidence intervals lie.

They are increasing rates on the basis that the current unemployment rate is ‘below’ the point estimate of the NAIRU but statistically they have no way of knowing whether the current unemployment rate is above the NAIRU of 3.5 per cent.

She claimed in that speech, that:

But given what we are seeing in the data, right now we feel comfortable about being a bit more specific than that.

How?

Movements in wages.

Okay, maybe.

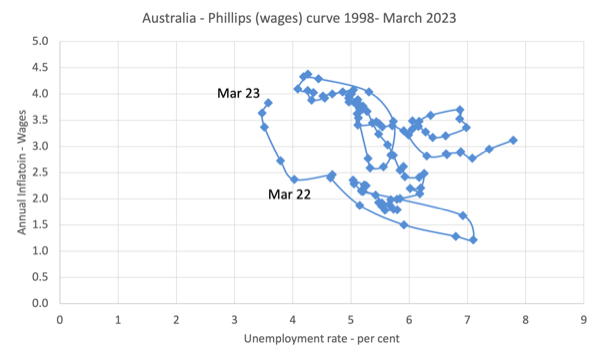

But have a look at this graph, which shows the relationship between the official unemployment rate for Australia on the horizontal axis and the annual rate of growth in the Wage Price Index (wages growth) on the vertical axis.

The sample is the September-quarter 1998 to the March-quarter 2023 (latest data).

The unemployment-wage inflation relationship is all over the place and it would be hard to make judgements about the relationship between the two variables using this data.

While there has been an acceleration in wages growth recently (still well below the inflation rate) it follows a drawn out period of record low wages growth.

So, we may be just seeing an adjustment back to more normal behaviour.

But trying to get any clear impression on when the relationship flattens out – so that the unemployment is associated with stable inflation – is virtually impossible.

Eyeballing the data could generate a NAIRU estimate of 4 per cent or even nearly 7 per cent.

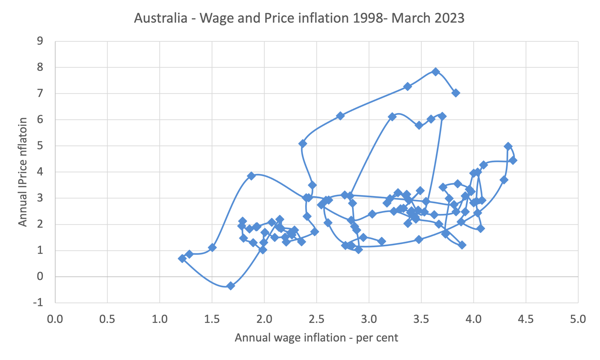

And to compound the confusion, here is the relationship between annual wage inflation (horizontal axis) and annual price inflation (vertical axis).

In the current period, wages growth increased over the last 6 months, yet CPI inflation is falling at a time when the unemployment rate was falling (see previous graph).

I can do endless comparisons like this and the result will be that there is no systematic, detectable or stable relationship between unemployment rates and movements in wages.

Recent RBA comments

Earlier this week (June 20, 2023), the Deputy Governor of the RBA was in Newcastle for a business event (they duchess business regularly) and her speech was entitled – Achieving Full Employment.

She claimed that “just because our inflation objective has been in focus recently, it does not mean that the other part of our mandate – maintaining full employment – has become any less important. Full employment is, and has always been, one of our two main objectives.”

Well that is their responsibility under the Reserve Bank Act 1959 so it has to be one of the objectives.

But the way they have got round that legislative responsibility and started using unemployment as a policy tool rather than a policy objective was to redefine what full employment meant.

That is what the NAIRU is about.

Rather than expressing full employment as the number of jobs that are required to satisfy the demand for work by the labour force, mainstream economists claimed that the NAIRU was full employment – which ties the concept to stable inflation.

So in the 1980s, after the chaos of the oil shocks my profession had the audacity to claim that full employment was around 8-9 per cent unemployment, because their stupid NAIRU models delivered that outcome.

Then as the unemployment rate fell again to much lower levels yet inflation did not accelerate, they had to revise the NAIRU estimates down.

Total sham.

The Deputy Governor got caught up here.

She introduced the NAIRU into her Speech but then said:

When discussing full employment, in the context of a central bank’s mandate, economists typically talk about the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment – the NAIRU. I will come back to this concept. But, more generally, full employment means that people who want a job can find one without having to search for too long. As I will emphasise later, the number of hours of work that people can secure is also important in defining full employment.

So which is it?

Enough jobs or the NAIRU.

Confusion.

She later admitted that:

For monetary policy, our price stability mandate requires a narrower concept of full employment.

Narrower than enough jobs.

She then admitted that the RBA uses the NAIRU to determine whether there is full employment or not and that currently:

… employment is above what we would consider to be consistent with our inflation target.

So the aim is to destroy jobs and people’s livelihoods based on this concept that no-one can see or even estimate with any accuracy.

1. The labour force in Australia in May 2023 was estimated to be 14,527.7 thousand in seasonally adjusted terms.

2. Unemployment in May 2023 was 515.9 thousand resulting in an official unemployment rate of 3.55 per cent.

3. A 4.5 per cent unemployment rate would mean 653.7 thousand workers would be classified as unemployed.

4. In addition, more workers would enter hidden unemployment as the participation rate fell with the diminished job opportunities and underemployment would also rise.

5. So the RBA is wanting to deprive 137.8 thousand workers who are currently employed of the chance to work all because they think the NAIRU is at 4.5 per cent (or thereabouts), while, at the same time, knowing it could be somewhere between 2 and 7 per cent (approximately) at present and unstable over time.

Conclusion

A shocking indictment of where we have reached as a civilisation.

Background Reading

Regular readers will know that I have written about the NAIRU concept before and have done years of work on the topic:

1. My PhD thesis included a lot of technical work (theoretical and econometric) on the topic – beginning in the mid-1980s, when I was just starting out.

2. In my 2008 book with Joan Muysken – Full Employment abandoned – we analysed the technical aspects of the NAIRU in detail.

3. Many refereed academic papers.

4. The following blog posts (among others):

(a) RBA appeal to NAIRU authority is a fraud (February 23, 2023).

(b) The NAIRU should have been buried decades ago (December 9, 2021).

(c)The NAIRU/Output gap scam reprise (February 27, 2019).

(d) The NAIRU/Output gap scam (February 26, 2019).

(e) No coherent evidence of a rising US NAIRU (December 10, 2013).

(f) Why we have to learn about the NAIRU (and reject it) (November 19, 2013).

(g) Why did unemployment and inflation fall in the 1990s? (October 3, 2013).

(h) NAIRU mantra prevents good macroeconomic policy (November 19, 2010).

(i) The dreaded NAIRU is still about! (April 6, 2009).

So I think I am qualified to discuss the topic.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2023 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.