Last week – RBA wants to destroy the livelihoods of 140,000 Australian workers – a shocking indictment of a failed state (June 22, 2023) – I wrote about the sense of being in a parallel universe when one reads official statements from the Bank of Japan and juxtaposes them against the stream of statements coming out of other central banks. The day after I wrote that post (June 23 2026), the Japanese e-Stat service (the portal for Japanese government statistics) released the latest – Monthly CPI data – which showed that the annual inflation rate fell by 0.2 points to 3.2 per cent in May, on the back of significant easing in electricity and gas prices, in part the result of government policy aimed at reducing energy prices rises in the domestic economy. Here is some more about the parallel universe. I conclude that the experiment underway between central banks is indicating that Japan’s zero interest rate regime (with fiscal expansion) is not an inflationary factor. It has not driven dangerous shifts in inflationary expectations for businesses or households. Further, the decision by the Bank of Japan not to hike rates has reduced the cost-of-living squeeze on mortgaged households that is being imposed by the (transitory) inflationary pressures. By way of contrast, other central banks have imposed extra burdens on those with debt and are engineering a massive redistribution of income from poor to rich into the bargain. As they continue with their blindness, they are risking recession and a major rise in unemployment, which will add to the pain the citizens are enduring.

Summary results

1. Inflation rose by 3.2 per cent in the 12 months to May 2023, down from 3.4 per cent in April.

2. The main contributors were processed food, durable goods, mobile phone handsets and hotel fees.

3. Falling electricity and gas prices reduced inflation.

4. Taking energy out of the index, shows that the CPI rose to 4.3 per cent, up from 4.1 per cent.

More detailed comparison with the US

I have noted previously how the mainstream economics media has hardly commented on the global experiment that is now clearly underway courtesy of the stark difference in monetary policy approach to the inflationary pressures in Japan compared to the rest of the world.

There is a near consensus of central banks that sees interest rates being hiked at present and the officials are claiming they are ‘winning’ the war against inflation, when the latter has already peaked and is falling for reasons quite apart from what the central banks are doing.

Clearly, the Bank of Japan is running in an entirely difference direction to the New Keynesian macroeconomic consensus, which I consider to be an experiment as to the veracity of the mainstream approach.

I have commented on this experiment before:

1. Japan has lower inflation, no currency crisis and its citizens are better off as a result of the monetary-fiscal policy initiatives (May 4, 2023).

2. Former Bank of Japan governor challenges the current monetary policy consensus (March 22, 2023).

3. Bank of Japan continues to show who has the power (January 26, 2023).

4. Bank of Japan has not shifted direction on monetary policy (December 22, 2022).

5. The monetary institutions are the same – but culture dictates the choices we make (December 8, 2022).

6. Two diametrically-opposed approaches to dealing with inflation – stupidity versus the Japanese way (October 6, 2022).

7. Why has Japan avoided the rising inflation – a more solidaristic approach helps (July 4, 2022).

8. We have an experiment under way as the Bank of Japan holds its cool (March 31, 2022).

Japan has experienced all the global supply shocks that other nations have endured that imparted the inflationary pressures.

Japan imports almost everything!

Yet, the Bank of Japan has not increased its policy interest rate and has held the line on the yield targetting for the 10-year Japanese Government Bond.

The Japanese government also relaxed fiscal policy further to deal with the cost-of-living crisis – provided fiscal transfers to households and subsidies to business as part of a deal to compress profit margins.

Meanwhile the corporations elsewhere are gouging profits to their hearts’ content because our governments refuse to pressure the corporate sector into the same sort of behaviour that the Japanese government has succeeded to extract from its price setters.

As a result of its policy stance, the Japanese currency has been attacked relentlessly by the ‘short-sellers’ in the financial markets who think they can bluff the Bank into changing policy and delivering massive profits to the speculators.

The Bank has refused to be bluffed and, has instead, inflicted large losses on the short-sellers.

I discuss that issue in the third (3) blog post cited above.

Here is an update using the data to May 2023.

The current annual inflation rate in Japan (All Items) (May 2023) is 3.2 per cent down from the peak of 4.4 per cent in January 2023.

For the US, the peak was 8.3 per cent in August 2022 and the current rate is 4.1 per cent.

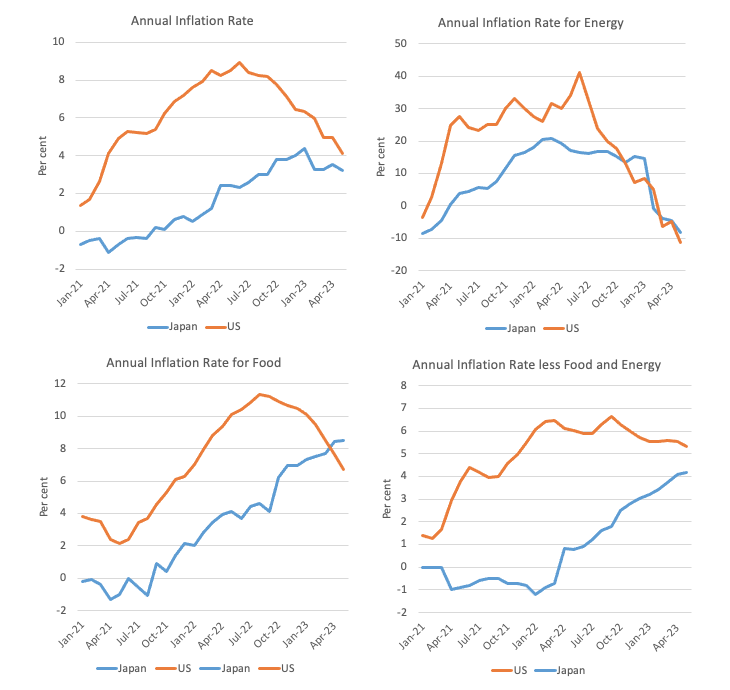

The following four-panel graph captures the key aggregates from January 2021 to March 2023 in per cent per annum terms.

The dynamics are similar – energy prices rose quickly which pushed up the All Groups indexes in both nations.

Japan is more exposed to imported food price shocks than the US and the lagged impact on the production and transport sector of the energy price inflation is evident on food prices.

Soon, those lagged impacts will dissipate and the headline figure in each country will decline.

While the overall inflation rates are falling in both countries, it is hard to mount a case that interest rate rises in the US have been the source of this arrest in US inflation.

The common dynamic is the energy price inflation, which was driven by cartel behaviour in the face of the pandemic supply constraints.

Household price expectations in Japan

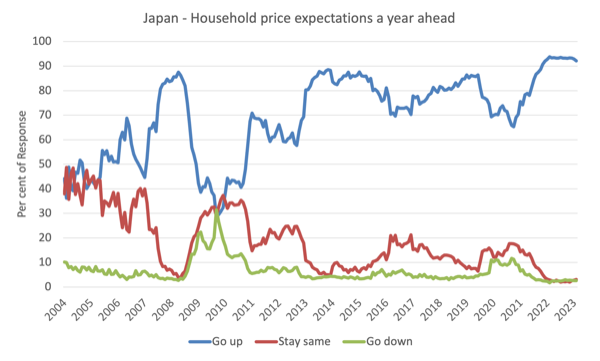

Japan’s Cabinet Office published the monthly – Consumer Confidence Survey – which includes data on ‘price expectations a year ahead’ among households.

The latest data shows that:

1. A declining proportion of respondents expected prices to be higher in 12 months in May – a decline of 0.1 points to 93.1 per cent.

2. The proportion of respondents expecting prices to stay the same, rose in May by 0.3 points to 2.7 per cent.

3. There was a decline in the proportion that expected prices to go down by 0.2 points.

So effectively, more Japanese households are now believing the inflation peak has past.

The following graph shows the evolution of the household expectations in the three groups from 2004 to May 2023.

Business Inflation Expectations in Japan

The basic New Keynesian theory, which is regularly invoked by central bank governors to justify them continuing to hike interest rates even though inflation rates peaked sometime in the last two quarters of 2022, is the concept of inflation expectations.

This is particularly apposite to any analysis of the Japanese situation given they have steadfastly maintained what is considered to be a highly expansionary monetary and fiscal policy stance in the face of rising inflation rates, sourced from imported supply shocks.

New Keynesians assert that prices are adjusted to accord with expected inflation. With rational expectations, the mainstream models predict that inflation will respond one-for-one with shifts in expected inflation.

And after a period of low inflation, as the inflation rate rises, people are conjectured to build that into their forward-looking behaviour via rising expectations and that then drives the inflation rate once the initial factors abate.

The RBA governor continually claims that if they leave the inflation rate to resolve more slowly as the supply factors become less significant then the persistence will become self-fulfilling via the risingh inflationary expectations.

It is hard to see that sort of process unfolding in any of the countries I have examined closely in the last few months.

Certainly, one cannot establish the New Keynesian causality in Japan.

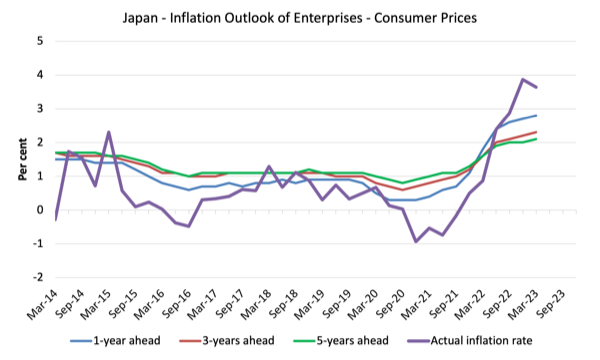

The following graph is taken from the – Tankan Summary of “Inflation Outlook of Enterprises – the latest data being released on April 3, 2023, covering expectations up to March 2023.

Firms are asked to assess the future price movements in output prices and consumer prices.

The following graph shows the business outlook for consumer prices – 1-year ahead, 3-years ahead and 5-years ahead. It also includes the actual inflation rate (thicker Purple line).

The expectations lag behind the actual evolution of the inflation rate.

What is interesting is the sharp arrest in rise of expected inflation in mid-2022 even though the overall inflation rate continued to rise.

Now as the CPI peak has passed, the expectations are largely static and should flatten in the coming

Given the April data above has shown that the inflation rate is heading down relatively quickly, I expect the next Tankan Survey will show the expectations data also to be falling.

The point is that the data cannot support the view that the overall inflation is persisting at higher levels because of the expectations.

I also investigated using econometric time series regression techniques the possibility that there is a relationship between changes in interest rates set by the central bank and the dynamics of the inflation rate for both the US and Japan, going back to January 1970.

I won’t report the results here given their technical nature but in plain English I found:

1. No systematic relations of statistical significance (even at 10 per cent level) using a range of lagged interest rate terms.

2. A weak positive relationship could be detected – meaning as interest rates rise, inflation rises – but it was not statistically significant.

3. I tested for structural breaks etc.

In other words, the current monetary policy shifts in the US are unlikely to be the reason the inflation rate is falling back and converging with the lower Japanese inflation rate.

The common factors are the supply constraints that arose during the pandemic and then the Ukraine and OPEC+ influences.

All of which have no sensitivity to the Federal Reserve interest rate decisions.

Conclusion

My conclusion so far, as I update the data each month to see where we are at, is that the experiment is indicating that Japan’s zero interest rate regime (with fiscal expansion) is not an inflationary factor.

It has not driven dangerous shifts in inflationary expectations for businesses or households.

Further, the decision by the Bank of Japan not to hike rates has reduced the cost-of-living squeeze on mortgaged households that is being imposed by the (transitory) inflationary pressures.

By way of contrast, other central banks have imposed extra burdens on those with debt and are engineering a massive redistribution of income from poor to rich into the bargain.

As they continue with their blindness, they are risking recession and a major rise in unemployment, which will add to the pain the citizens are enduring.

I prefer the Japanese approach.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2023 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.