There appears to be confusion among those interested in Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) as to what the implications for a green transition that will fasttrack the transition to renewable energy will require by way of government. I regularly see statements that government deficits will have to be ‘massive’ for extended periods because the private (for profit) market entities will not move fast enough to deal with the climate emergency in any effective way. The confusion inherent in these claims is that they fail to separate the ‘size’ of government from any particular ‘net spending’ (deficit) recorded by government. The two outcomes are quite separable and have to be if government action is to achieve sustainable outcomes, not only in terms of environmental goals but also price stability goals. So let’s work all that out. Failing to do so, leads MMT activists to make claims that open them up to criticism from those who understand the point I am making but have different ideological agendas. So they make erroneous claims such that ‘MMT just advocates big deficits’, or that ‘MMT thinks that deficits do not matter’. But they have been lured into that position, in part, by the social media behaviour of some MMT activists.

In the British Financial Times last week (June 29, 2023), there was an article – The energy transition will be volatile – from the US energy editor for that newspaper who was reflecting on his experience in that job as he prepares to move on to another position.

In part, the editor collected his thoughts about the “new clean energy arms race” and his basic message was that:

Capitalism won’t deliver the energy transition fast enough …

That has been a constant message from my work in this area also.

My view is that for the world to achieve environmental sustainability concurrent with reversals in the rising income and wealth inequality (so that we also achieve better outcomes for those in poverty and hardship), we will have to move away from a system that privileges resource allocation decisions based on the pursuit of private profit, to a more societal-based system.

Socialism?

Using that terminology will immediately provoke the fanatics who haven’t moved on from reading about Stalinist purges in 1937-1938 and weaponise the term Socialism to advance their own unsustainable agendas.

I will write more about what a societal-based system of resource allocation might encompass free of that sort of emotive claptrap in future blog posts and forthcoming book.

But you can get a flavour for my thinking from the 2017 book we wrote – Reclaiming the State: A Progressive Vision of Sovereignty for a Post-Neoliberal World (Pluto Books, September 2017).

But the point the FT article is making is sound:

There’s too much to do, and given the urgency and the need to get the solution right, this isn’t a task for your favourite ESG-focused portfolio manager or the tech bros. The sheer scale of the physical infrastructure that must be revamped, demolished or replaced is almost beyond comprehension. Governments, not BlackRock, will have to lead this new Marshall Plan. And keep doing it.

I covered some of these ideas in the following blog posts:

1. The climate emergency requires us to reset our understanding of fiscal capacity. It is already, probably, too late (May 11, 2023).

2. An MMT-Green New Deal and the financial markets – Part1 (September 2, 2019).

3. An MMT-Green New Deal and the financial markets – Part 2 (September 5, 2019).

The point is that so-called Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) financial market speculation is just the latest opportunistic arena for the big investment banks and hedge funds to pursue profit.

The motivation is not to advance societal well-being but to further enrich the shareholders of these companies.

And when the two missions become contradictory the latter always wins.

The same sort of corporations were the ones who developed speculative derivative products to make profits by taking long positions in food products – like corn.

By hoarding the product they were able to create shortages which pushed the price up – thinking how smart they were into the bargain as they cashed in on the gains.

There was never any regard given to impact of the food shortages for the indigenous communities around the world who depend on every grain of corn and whatever for day-to-day nourishment.

The screen jockeys just saw dollar signs.

Remember the ‘burn, baby, burn’ boys from Enron who celebrate a natural disaster because it generated more profits for the company and commissions for themselves (Source)

Which is why we should avoid thinking that ‘green financing’ of energy transition will deliver anything that is desirable.

It is also clear that we will need to use ‘social’ calculus rather than ‘private’ calculus to justify the sort of shifts that are required.

Capitalism works via ‘private calculus’ where decisions are made about resource allocation (where inputs are used and what products are made) based on what the decision ‘costs’ the private owners against what the private owners expect to gain.

All sorts of financial ratios and mathematics are deployed to supplement the ‘seat of the pants’ feelings (Keynes’ ‘animal spirits’) reasoning.

The problem is that social costs and benefits – those that are not included in the private calculations – may be large but are ignored.

The classic pollution at the back of the factory situation which the factory doesn’t pay for leads to overproduction and environmental degradation from a societal perspective.

In many cases, if those social costs were included in the ‘market price’ of the factory’s products, then no-one would buy them, which means the factory should never have been allowed to operate in the first place.

There is also the problem of ‘carbon offsets’ that allow for speculative activity among financial market players, but which often result in first-world pollution continuing while poorer communities around the world are devastated by some new project designed to count as an ‘offset’, but which undermines local sustainable practices or destroys buildings etc.

So, I agree that the scale of what is needed in the next period of human history to render our activities sustainable with the planet that supports us is beyond the scope of private financial markets to ‘fund’.

The FT article then claimed:

The western nations that did so much of the damage will have to finance the transition in the developing world — it is astonishing that this idea is still debated. Massive deficit spending will be necessary, not a new ETF.

So we should not think of the solution in terms of seeking funding from private derivatives markets (the ETFs – exchange-trade funds).

But the problem with this statement is the assertion that “Massive deficit spending will be necessary”.

I see that claim often tweeted by MMT activists too.

The problem is that it blurs the distinction between the net spending position of a national government (fiscal deficits) and the size of government in resource allocation terms.

A large government does not necessarily mean a large fiscal deficit.

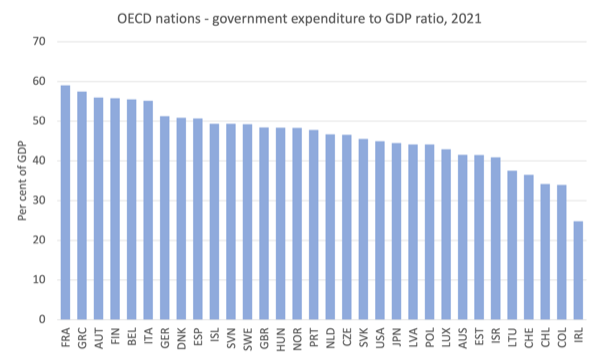

The next three graphs demonstrate the point.

The data is from the OECD database for 2021.

The size of government is often measured using the ratio of government expenditures to the total output of the economy (GDP) although there are some issues with that measure (it can move because government has increased its command of resources, or because the resources governments are using have increased in price).

There is a literature available that discusses the various ways in which we can measure the size of government and the pros and cons of each.

I won’t go into that here and will use the common measure as above.

The point is not to get precision here but to provide readers with a sort of ‘ballpark’ understanding that government size varies considerably.

Using this dataset, we see that Ireland’s public expenditure to GDP ratio in 2021 was 24.8 per cent (the smallest) while the largest was France at 59.0 per cent.

The next graph shows the considerable variation in between these two outlier nations.

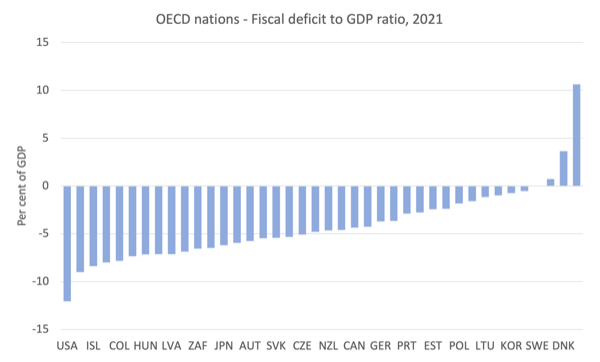

The next graph shows the fiscal positions of the OECD nations (where published) in 2021.

Once again, we observe considerable variation across the sample.

In 2021, Norway was running a fiscal surplus of 10.6 per cent of GDP, while the US was running a 12.1 per cent fiscal deficit.

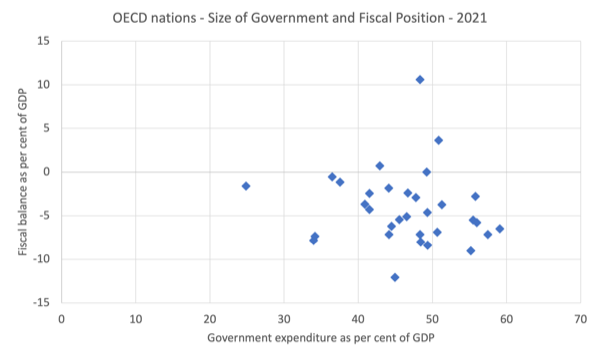

The final graph brings the two separate measures together into a cross plot with the fiscal position on the vertical axis and the size measure on the horizontal axis.

You can see that nations of similar size ran vastly different fiscal positions in 2021, for various reasons.

And countries that have similar fiscal positions in 2021 have vastly different size of government.

There is no general tendency that we could establish using statistical techniques.

The conclusion is that the size of government does not tell us anything systematic about the size of the fiscal deficit in any particular year.

Bigger governments run small deficits and some run larger deficits.

Smaller governments run large deficits and some run small deficits.

Green transition – size of government

Consistent with my opening point that we will have to move away from a system that privileges resource allocation decisions based on the pursuit of private profit, to a more societal-based system, I conjecture that a Green Transition to renewables and less-energy use overall will require a ‘massive’ increase in the size of government in many nations.

As the FT article notes – “the sheer scale of the physical infrastructure that must be revamped, demolished or replaced is almost beyond comprehension.”

For example, the private housing stock that can be retrofitted is enormous and the task is beyond the scope of private individuals.

Rebuilding public transport system that have become degraded through privatisation and profit gouging will be essential.

Restoring public ownership of electricity generation and supply and ridding nations of gas usage will be essential.

Building localised community farms to provide sustainable production and food security will require large government investment.

There are a lot of other dimensions to the challenge that will require increased public resource usage.

The question then, and the point of this blog post, is what are the implications of necessarily increasing the size of the government’s footprint on the economy for the likely fiscal positions?

Will we require ‘massive deficit spending’?

Note that the terminology ‘deficit spending’ is also problematic in that there is no difference between government spending that is associated with a final fiscal surplus and spending associated with a deficit.

Spending is spending and is executed in the same way – crediting bank accounts in the main – regardless of the overall fiscal position.

What the FT author meant was that there would be a large increase in recorded fiscal deficits required – such that net government spending would have to increase substantially.

Well, I don’t think that will be possible.

Yes, the size of government must increase ‘massively’.

But that very requirement will likely place a major strain on the available productive resources which will require offsetting measures to reduce the ability of the current users of those resources to actually deploy.

What does that mean?

Simply, that the situation that the global economy is currently in is biased towards inflationary pressures.

First, we have seen what the pandemic did to supply availability and how quickly that translated into price inflation given that demand was maintained via government income support measures.

Second, we have seen the capacity and willingness to profit gouge demonstrated as those supply constraints have abated.

In part, this is due to the earlier privatisations of energy, transport, water etc which have placed these essential activities in the hands of profit-seeking corporations who are willing to forego public interest for private gain.

Third, Covid has left a significant number of worker unable to work at all or at the previous level. We can expect on-going labour shortages in key areas which will require extensive retraining elsewhere.

So a large net government spending impluse would not be sustainable at present despite the urgency for increasing the size of government.

What will have to accompany the increasing government command of productive resources, to redirect them into sustainable uses, are significant offsetting measures.

Yes, rules-based regulations can create free resources by stopping private use.

Yes, price controls can stop profit gouging and all countries should already be using them.

Yes, the government can alter administrative arrangements which tend to index prices of particular services to CPI movements and/or impose levies on commodities which increase prices (for example, fuel excises).

Certainly, we can relax them as we better understand the fiscal capacity of governments – see first-linked blog post above.

But I doubt whether these type of measures or changes will be sufficient to provide sufficient resource space for governments to expand within to meet the climate challenge without causing inflationary pressures.

So we are left with the old faithful – bogey person – increased taxes.

I am convinced that governments will have to increase taxes to reduce private disposable income and free up resources in order to meet the challenge.

That means that while government expenditure relative to the scale of the economy will have to increase ‘massively’ (hence the size of government will increase), the tax revenue will also have to increase, not to fund the spending but to reduce the capacity of the existing private users of the extant resource base to enjoy that usage.

In other words, fiscal deficits might rise a bit but they might also fall depending on the context, which is defined by the available fiscal space.

And remember, MMT defines fiscal space entirely differently to mainstream economists.

We think of fiscal space in terms of the available real productive resources that can be brought into use without causing inflationary pressures as a result of government having to compete with existing users of those resources at market price.

Conclusion

Massive government size does not necessarily mean massive fiscal deficits.

We have to be very careful to separate those two when making public statement.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2023 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.