In the early 20th century, a new business model appeared: the mail-order home. Companies would mail out catalogs containing several dozen different home options, buyers would send in their orders, and the company would send the necessary materials – pre-cut lumber, roofing, millwork – along with instructions for correct assembly.

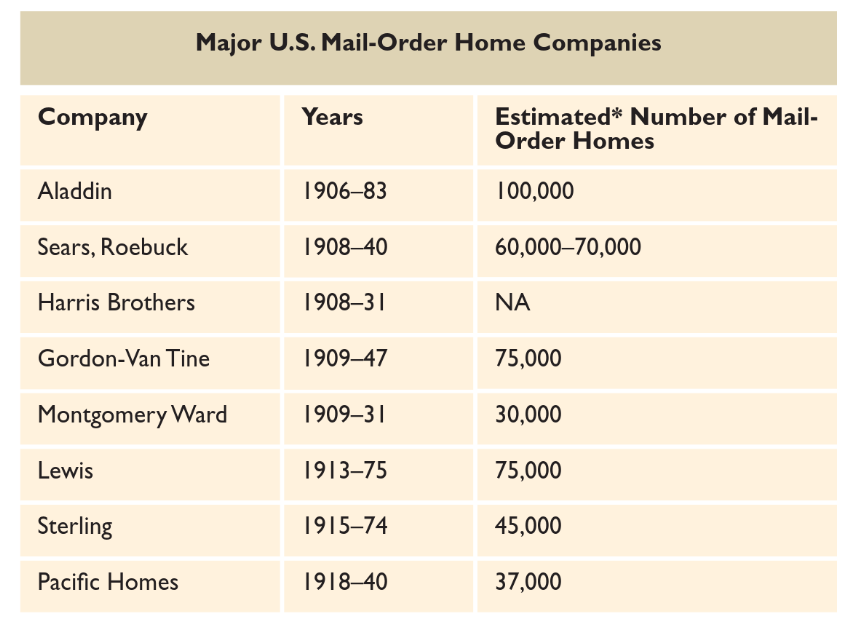

Sears, by far the best known mail-order home company, sold its “Sears Modern Homes” from the early 1900s through the 1930s. But Sears was just one of many companies with this business model. Other companies had been selling pre-cut homes for more than 10 years by the time Sears entered the market, and mail-order home companies continued to operate into the 1970s, several decades after Sears had left the business.

What made the mail-order home suddenly become popular? Why has it faded away? Let’s take a look.

Several factors combined to create the rise of the mail-order home.

One was the development of the American railroad network, which grew enormously in the second half of the 19th century. In 1840, there were about 3000 miles of railroad track in the US. By 1860, there were 60,000, and by 1900 there were nearly 200,000.

The railroad massively decreased the time and expense required to move freight across the US. In 1800, a trip from New York to Chicago took 6 weeks to complete. By 1860, the same trip took less than 3 days. Between 1815 and 1860 the costs of moving manufactured goods over land fell by 95%.

As the railroad network grew, Americans increasingly moved west. In 1861, only 14% of the US population lived west of the Mississippi. By 1890, that had risen to nearly 27%, most of them farmers. And manufacturing output grew as the railroads made it possible to ship goods long distances to more customers. Between 1859 and 1899, the value of manufactured goods produced in the US increased from just under $2 billion to over $11 billion.

The mass migration, the explosion in the availability of manufactured goods, and cost-effective transportation over distance enabled the mail-order catalog. Instead of buying from their local store, with its limited selection of products, buyers could now have purchases delivered from a catalog with a huge selection of goods. The first mail-order catalog selling a wide variety of goods was Montgomery Ward, which formed in Chicago in 1872. By the 1880s, Montgomery Ward’s catalog was 540 pages and listed 24,000 items, available for purchase across the country. In 1889, Sears (under the name “The Warren Company”) put out its first catalog, which by 1895 was over 500 pages.

The mail-order catalog business was helped along by the development of the US Postal Service. Between 1871 and 1901 the number of post offices more than doubled, from 30,000 to nearly 77,000. In 1879 catalogs became classified as “aids to the dissemination of knowledge,” which entitled them to very low postal rates of one cent per pound. And in 1896, the US established free delivery for rural customers (prior to this, rural customers had to pick up their mail at a local post office).

As the mail-order catalog businesses grew, companies expanded the range of products they offered. By 1900, both Sears and Montgomery Ward sold building materials such as nails, screws, doors, windows, and gutters.

Better postal service also enabled another new type of business: mail-order house blueprints. Customers could choose a house design from catalogs issued by architects such as George F Barber or William Radford, and the company would mail a set of blueprints necessary for constructing the house.

The mail-order blueprint company evolved from “pattern books,” which were collections of home designs and architectural details aimed at aiding “unschooled builders and homeowners” (Schweitzer 1990). Pattern books had been popular in the US since the 1830s, and following the Civil War pattern book companies began to sell blueprints of the homes shown in them.

Eventually the mail-order catalog companies, such as Sears and Montgomery Ward, adopted and adapted the mail-order blueprint idea. In addition to home blueprints, the companies offered the materials, such as lumber and millwork, needed to build the house. However, these were bulk materials, not specifically designed for the house in question.

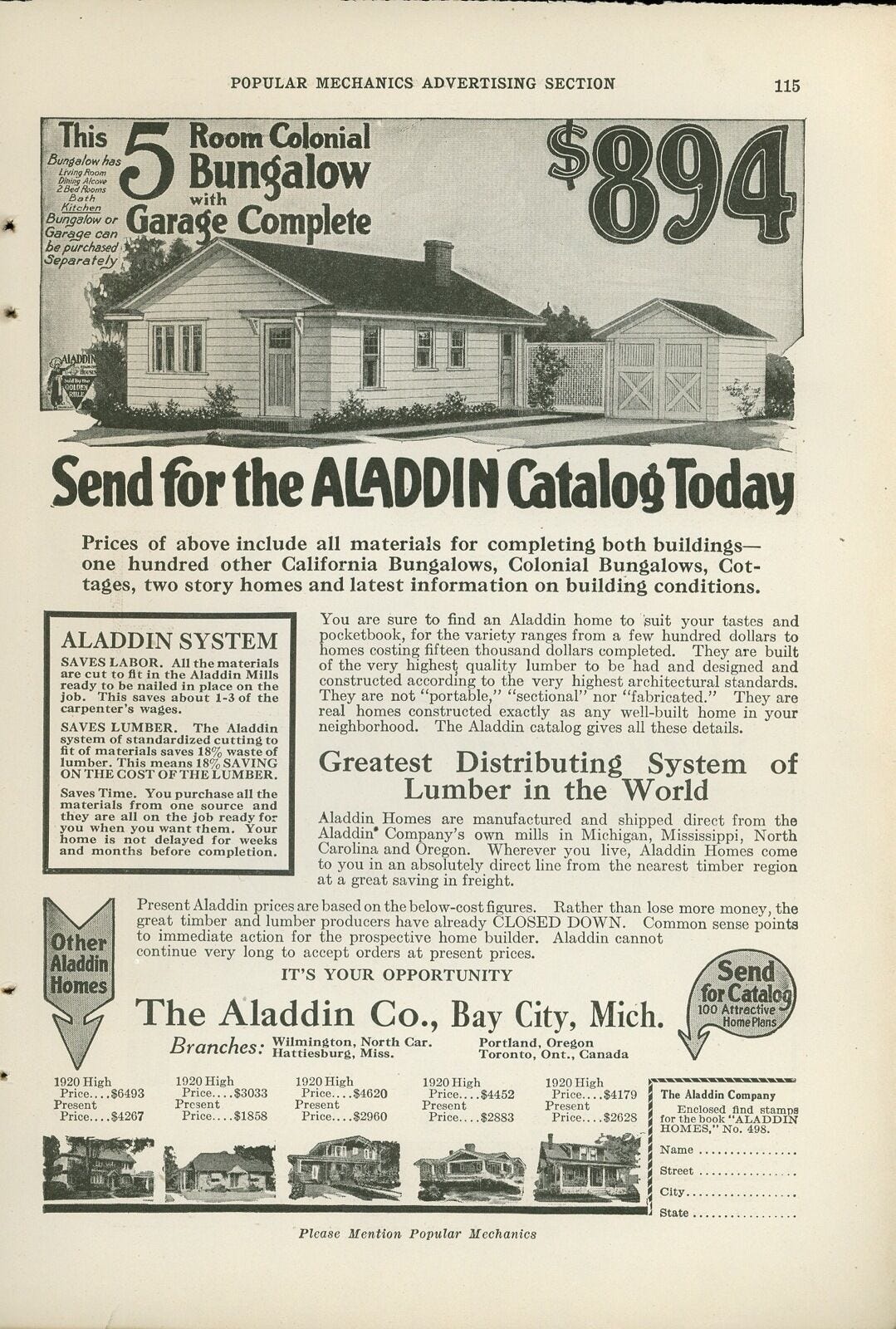

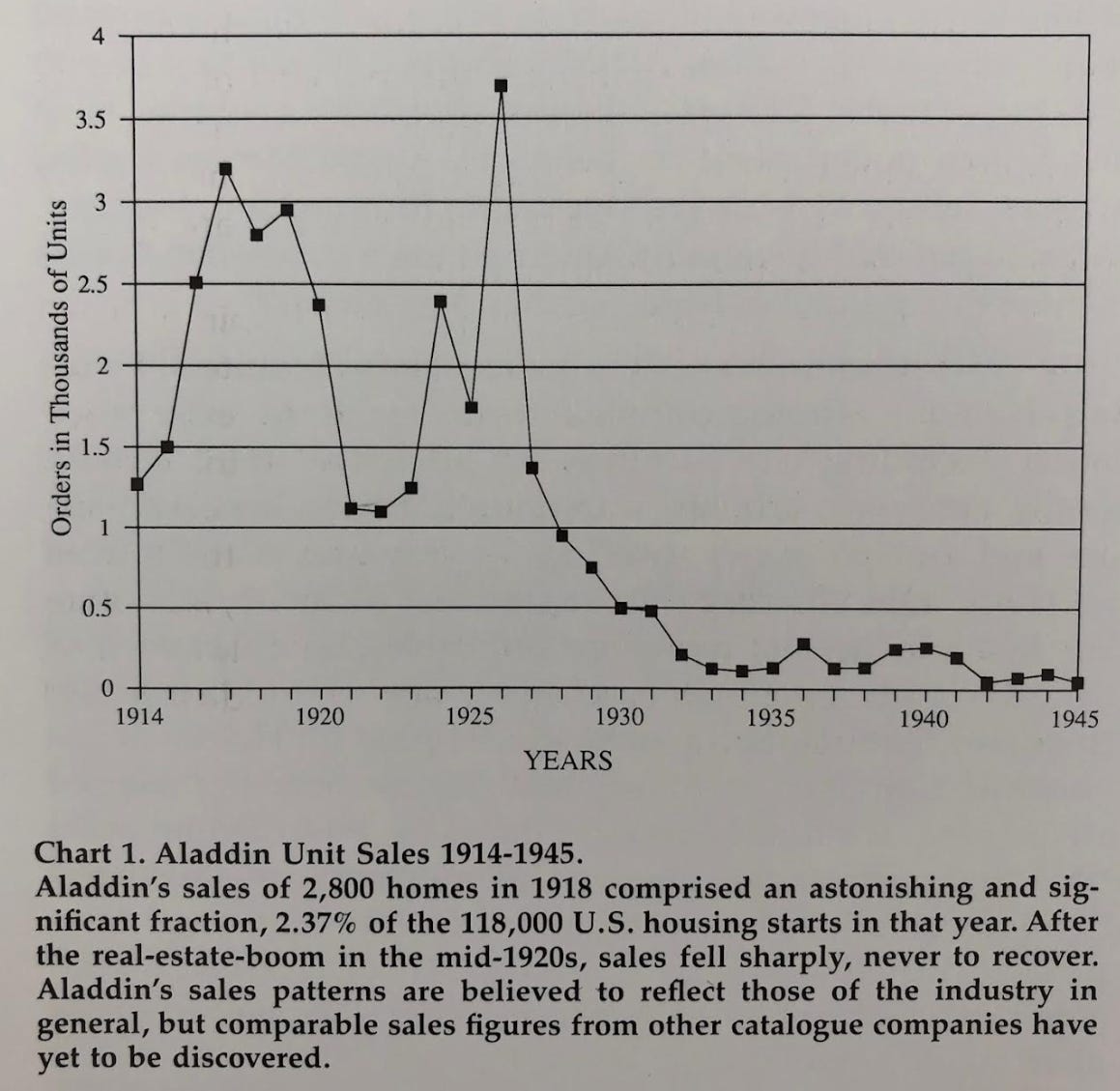

What we think of as the mail-order house – picking a home out of a catalog, and receiving specific, pre-cut materials for it and instructions for how to put it together – didn’t begin with Sears, but (likely) began with another company, Aladdin Homes of Bay City, Michigan. In the 19th century Bay City had become a center of shipbuilding, and several companies began to sell “knock-down boats” in the early 20th century – customers would order a boat, receive the parts for it, and then assemble the boat themselves. Two brothers, WJ and Otto Sovereign, got the idea to sell houses the same way. In 1906 they formed the North American Construction Company (later changed to Aladdin Homes), and sold their first home in 1907. By 1914, Aladdin was selling over 1000 homes a year.

Unlike the Sears and Ward home offerings, which were simply blueprints paired with bulk materials, the Aladdin Homes consisted of pre-cut materials made for the specific home in question. See the exhaustive list of materials included in a 1919 Aladdin Homes Catalog:

Center sill foundation timber cut to fit. Joists, studding, rafters, and ceiling joists all accurately cut to fit. Sheathing lumber cut to fit. Sub-floors cut to fit. Joist bridging cut to fit. Building paper for all dwellings for side walls and floor linings. All bevel siding, every single piece guaranteed to be cut and to fit accurately. Shingles or siding for the wide walls, whichever preferred, will be furnished for any house at no additional cost. Outside finishing lumber, all cut to fit. Flooring, cut to fit. Roof sheathing, cut to fit. Porch timbers, joists, flooring, columns, railing and posts, roof sheathing, all and every piece cut to fit except porch rail, uncut. Extra Star-A-Star Cedar Shingles or prepared roofing. Outside steps of all dwellings cut and shaped to fit. All doors mortised with frame and trim inside and out. Windows and frame, sash and glass, and trim inside and out. Moulded base board for all rooms, not cut to fit. Weather moulding for trimming all outside doors and windows, cut to fit. Crown mould, cove mould and quarter round mold, etc. Stairways, treads, risers, stringers, newel posts, balusters, moulding, etc. for all two story houses cut to fit. All hardware. Mortise locks, knobs, and hinges, tin flashing, hip shingles, galvanized ridge roll, window hardware, etc. Nails of proper size for entire house. Paint for two coats outside body and trim (and colors), putty, stains and varnishes. Lath and plaster and grounds for lining entire house. Complete instructions and illustrations for doing all the work. – Aladdin Homes Catalog, 1919

Aladdin was quickly joined by competitors, several in Bay City, which became a hub for the mail-order home industry. Lewis Homes, which started as a fabricator for Aladdin, started its own mail-order homebuilding company in 1913. Sterling Homes, another Bay City company, began selling pre-cut homes in 1915. Sears actually joined the party somewhat late – it didn’t offer pre-cut homes until 1916. Montgomery Ward didn’t offer them until 1918. By the 1920s, eight large companies sold mail-order homes, along with many smaller ones. Over their lifetimes, these companies would collectively sell hundreds of thousands of homes.

Though they all had the same basic business model, specific offerings varied significantly between companies. While all the mail-order companies offered pre-cut lumber and millwork, some included materials for services such as heating, plumbing, or electricity. As late as the 1950s, Aladdin did not include mechanical, electrical, or plumbing late in its homes, whereas Sears included these as options as early as 1919. And though they all included assembly instructions, Sears labeled each individual component based on its position in the house. Most companies did not include bricks or concrete in their materials, though Sears offered drywall long before it became a standard material for interiors.

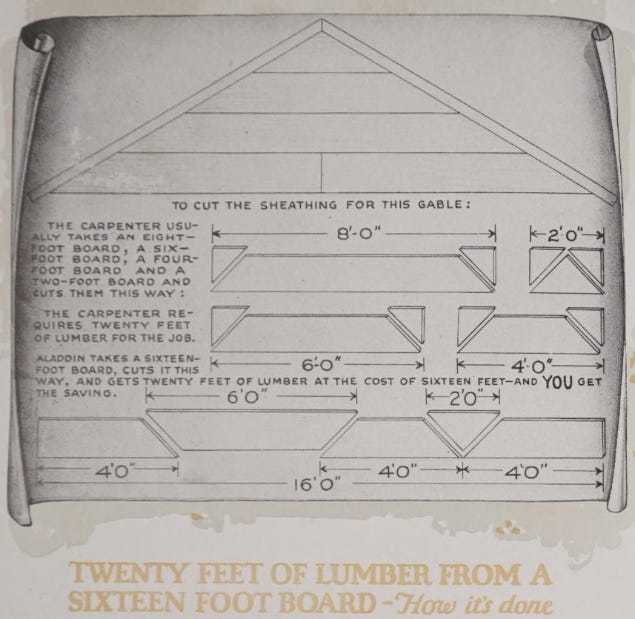

The mail-order companies advertised heavily, both via the catalogs themselves (which emphasized how much money could be saved via a pre-cut home) and in magazines such as Popular Science, Cosmopolitan, and the Saturday Evening Post. By cutting all the lumber in a centralized location with specialized equipment, the mail-order companies boasted that they could achieve significant savings. Aladdin advertised its “mill genie,” a $50,000 sawing machine that could cut lumber components faster and more efficiently than any carpenter could. And by intelligent arrangement of cuts, Aladdin was able to get more useful boards out of a given amount of lumber than a site-builder would be able to. Sears likewise claimed that its homes saved hundreds of hours of construction labor by using pre-cut lumber.

Most mail-order companies offered other types of buildings as well as houses. Aladdin sold pre-cut gas stations, and both Sears and Aladdin provided pre-cut barns and agricultural buildings.

In some cases, mail-order homes were used to build entire towns of dozens or even hundreds of homes. In 1914, DuPont ordered 61 homes from Aladdin for a town it built near its munitions plant in Virginia. In 1917, Aladdin delivered 252 homes to Birmingham, England, as worker housing for the Austin Motor Company. Sears sold homes for company towns to Standard Oil, Bethlehem steel, and other companies (a check for $1,000,000 from Standard Oil for homes was reportedly the largest check Sears had ever received from a customer to that point), and Montgomery Ward advertised its several dozen corporate customers. Mail-order industrial housing proved so popular that Aladdin created a special industrial catalog, offering to fabricate anything from single homes to complete cities, including schools, stores, churches, banks, and other necessary buildings, along with water and sewer services.

What happened to the mail order home companies?

Most of them seem to have gone out of business during the one-two punch of the Depression and WWII. Sears, Montgomery Ward, and Harris all closed their homebuilding operations in the 1930s as sales dropped (though Sears would attempt some sporadic revivals). As we’ve previously noted, prefabricated construction companies often struggle during economic downturns, as they’re unable to support their large factory overheads. Pre-cut home factories were often extensive operations, whose high cost was hard to support when production volumes dropped.

Sears’ homebuilding operations were also impacted by losses from its mortgage operations. Beginning in 1911, Sears began to offer mortgages along with house plans and building materials. Sears’ lending policy was “continually relaxed” over time in response to pressure to make more sales, resulting in huge losses during the Great Depression. Sears’ losses on mortgages ended up exceeding the value of all the profits the homebuilding division had earned over its 25-year life.

Following WWII, the mail-order model seems to have fallen in popularity. Aladdin’s sales dropped from several thousand homes a year to a few hundred a year, even as housing starts overall rose. But the Bay City trio of Aladdin, Lewis, and Sterling managed to survive into the 1970s, with the last of them, Aladdin, ceasing operations in 1983, likely finished off by the housing downturns of the 1970s.

Some experts have posited the rise of competition from tract home builders (such as Levitt and Bohanan) full prefabricators (such as Lustron, National Homes, and Gunnison Homes), and mobile homes. Together, these methods of building outcompeted mail-order homes in the markets they targeted: cost-conscious buyers at the low end of the market, and those who wanted the convenience of all their house-components shipped directly to them.

This seems possible. It also seems likely that advancing building technology played a role. At the height of the mail-order home’s popularity in the 1920s, the amount of work that took place on-site in conventional construction was much higher than it is today. Roof rafters, floor joists, and exterior sheathing were all cut from dimensional lumber, windows, doors and cabinets were made on-site, and interiors were finished with lathe and plaster. All this work would have been done without the aid of power tools. In this sort of construction environment, the potential labor savings from cutting and machining in a factory would be considerable.

But over time, the level of prefabrication in conventional construction has risen. Construction increasingly made use of large sheet materials such as plywood and OSB for sheathing, and drywall instead of lathe and plaster. Roofs and floors began to be made from prefabricated roof trusses or I-joists. Windows, doors, and cabinets all became preassembled. Engineered flooring is designed to fit together and install quickly replaced conventional wood flooring. And the development of power tools meant that work that did take place on-site was easier to complete. Thus, mail-order’s advantages over conventional site-built have eroded considerably over time.

Mail-order was never an especially popular method of building: at its peak it was perhaps a single-digit percentage of yearly housing starts. As competition rose and advantages declined, its niche may have simply been whittled away.

We can think of prefabricated construction as existing on a plane, with “component size” on the x axis and “component complexity” on the y-axis. The mail-order home companies explored an interesting part of this space, using traditional building materials that were slightly more finished than conventional bulk materials. But it doesn’t seem as if the experiment was a success in the long term.

-

Stevenson and Jandl 1986 – Houses by Mail

-

Schweitzer and Davis 1990 – America’s Favorite Homes

-

Emmet and Jeuck 1950 – Catalogues and Counters

-

Hunter 2012 – Mail Order Homes: Sears Homes and Other Kit Houses

-

Chandler 1977 – The Visible Hand