The question is when is a Labour Party a Labour Party? The answer is: When it is a Labour Party! Which means when it defends workers’ interests against capital and when it defends families against pernicious neoliberal cuts or constraints on welfare. Which means, in turn, that the British Labour Party is a Labour Party in name only and the British people have little to choose from with respect to the two parties vying for government – Tory and Tory-lite! The British Labour Party has been abandoning its traditional role for some time now and while it is true that society and the constraints on government have evolved/changed, some things remain the same in a monetary economy. And that means that the statements from the Labour leader in recent days about fiscal spending austerity and a refusal to reverse some of the most pernicious Tory policies fail to recognise the reality. More spending will be required in the coming years not only to redress the damage done by the years of Tory rule but also to meet the challenges ahead in terms of climate, housing, education, health and more. The real question should be not whether more spending is required but what must accompany that spending by way of extra taxation. In my assessment, the next British government will have to lift taxes to create sufficient fiscal space in order to meet the challenges facing the nation with extra spending. Starmer is clearly not wanting to have that debate, which means the British people are once again being deceived by their political class. Taxes will rise with growth but I doubt that will generate sufficient space for the extra spending that will be required.

When I said in the introduction that a Labour Party is one that defends workers’ interests against capital I was obviously casting the analysis within a framework defined by the reality of class struggle.

I know that modern labour politicians around the world now waver about that and claim that it is too simplistic to use the labour-capital class conflict framework because there are all sorts of relevant classifications that usurp that starting point.

Here they are talking about the adoption by progressives of post-modernist identity politics where all gender, race, sexuality etc become the dominant focus.

And so we get progressives, for example, claiming that female workers have more in common with their female bosses than they do their fellow male workers on the shop floor.

And that that commonality is a more meaningful basis for analysis.

At least until the boss starts sacking workers or imposing punitive shifts in the working conditions or wage cuts in the interests of capital.

I am not suggesting that the identity issues are not unimportant.

Of course they are.

But they are typically exploited by capital as a way of fragmenting the collective interests of labour and unless we start with the intrinsic relationships in capitalism, then analytical errors will arise in the inferences we draw.

I obviously follow the economic situation in Britain fairly closely and also keep my attention focused on the political debate and have written about that extensively.

Remember the turning point on September 28, 1976, at the annual Labour Party conference in Blackpool.

British Prime Minister James Callaghan, aided and abetted by the untruthful Chancellor Dennis Healey (who lied about needing IMF funding), told the gathering that governments can no longer spend their “way out of a recession” and that the Keynesian approach was an option that “no longer exists”.

The Conference followed a period of clandestine activity between the US and British bureaucracies which was aimed to bring Britain to heel, one way or another and to overcome its ‘immorality’ – yes, the US thought the fiscal deficits the Brits were running were immoral.

Callaghan said (among other things in the Speech) that:

Britain faces its most dangerous crisis since the war … The cosy world we were told would go on for ever, where full employment would be guaranteed by a stroke of the Chancellor’s pen, cutting taxes, deficit spending, that cosy world is gone …

When we reject unemployment as an economic instrument – as we do – and when we reject also superficial remedies, as socialists must, then we must ask ourselves unflinchingly what is the cause of high unemployment. Quite simply and unequivocally, it is caused by paying ourselves more than the value of what we produce …

We used to think that you could spend your way out of a recession, and increase employment by cutting taxes and boosting Government spending. I tell you in all candour that that option no longer exists, and that in so far as it ever did exist, it only worked on each occasion since the war by injecting a bigger dose of inflation into the economy, followed by a higher level of unemployment as the next step. Higher inflation followed by higher unemployment.

I wrote about that in this blog post – The conspiracy to bring British Labour to heel 1976 (June 15, 2016) – which was part of a series where I traced the shift in the Labour Party to being a party committed to social democracy and the defending the interests of workers to being a party pursuing the interests of capital.

I refer you to that blog and its siblings for the detail.

But this statement represented a catastrophic shift in the British Labour Party from which it has never recovered.

It paved the way, much later for the Blairites to introduce New Labour.

It has also provided the mechanisms for the Right in the Labour movement to crucify Jeremy Corbyn and his allies both in the lead up to the last General Election (with the faux anti-semitist claims) and beyond with the purges of the Left under Keir Starmer.

In recent days, the current British Labour leader has made it clear where the Party sits in the ideological spectrum.

In an interview on the BBC program – Sunday with Laura Kuenssberg yesterday (July 16, 2023), he refused to answer the question – Will Labour government spend more money on public services? – claiming that the “way to invest in our public sector is to grow the economy”.

The BBC article (July 16, 2023) – Keir Starmer won’t commit to more money for public services – provides a summary of the interchange.

He claimed that also claimed that the housing shortage would be dealt with, not by spending more to build homes but by “reforming the planning system” – which means further deregulation and power to the property developers.

He doubled down on his Tory-lite credentials when he told the interviewer that the Party would not reverse the pernicious – two-chiild benefit cap – which is explained in this UK Guardian article (July 17, 2023) – What is the UK’s two-child benefit cap and how has it affected families?

This is a policy that discriminates against larger families and was claimed to provide incentives for parents of such families to search harder for work.

But the evidence is clear (Source):

It has affected an estimated 1.5 million children, and research has shown that the policy has impoverished families rather than increasing employment.

The analysis shows that for an additional £1.3 billion per year, 250,000 British children would escape their current poverty and 850,000 children would “be in less deep poverty”.

There are widespread calls for the cap to be eliminated, even from Conservatives who understand the policy to be “vicious”.

This policy belongs in the folio of neoliberal policies that are the most punitive in terms of working class attacks that the Tory-type governments around the world have introduced.

They directly damage disadvantaged peoples’ lives and fail to even meet their own so-called motives (in this case to increase employment).

They are at the worst end of the attacks on the poor that the neoliberals have contrived.

Yet, the British Labour leader has committed his party to extending them if they gain office.

This interview reminded me of Callaghan’s speech in 1976.

Further, on July 16, 2023, the British Labour leader wrote an Op Ed in The Observer – Labour will rebuild broken Britain with big reforms, not big spending. That’s a promise – sounded very much like Callaghan 2023 style.

It was actually interesting because he cited a number of issues that he defines as characteristics of a “broken” Britain (mortgage rate rises, etc) and said the reason for this crisis:

… is what happens when a government loses control of the economy.

Yet, he supports the situation where monetary policy – and the mortgage rate hikes – are the direct result of government handing control of a key macroeconomic policy tool to an unelected and unaccountable committee at the Bank of England.

This is under the guise of central bank ‘independence’, which the British Labour party has fostered.

The mortgage crisis is because governments have depoliticised a key policy tool and refuse to change that approach to macroeconomic policy.

He went on to talk about “recklessness” which is code for:

… promising vast sums of money to fix them …

And he outlined his sense of priority:

… economic stability must come first …

And his belief in the macroeconomic fictions of the mainstream:

That will mean making tough choices, and having iron-clad fiscal rules. The supposed alternative – huge, unfunded spending increases at a time when the Tories have left nothing in the coffers – is a recipe for more of the chaos of recent years and more misery for working people.

Apparently, “reform or bust” will make “Britain thinking big again” rather than investment.

First, reform always requires spending outlays if it means resources must be shifted, training and capital investments to be made.

Someone has to spend more – whether it be the private sector or the public sector.

Starmer clearly thinks the future is smaller government and larger ‘market’ allocation.

Yet the challenges he sets out – “clean energy, the NHS, crime” etc are areas that have suffered from an excessive reliance on the ‘market’ and a lack of government oversight and investment.

These areas will require larger government I suspect, which means more public spending.

But we should not confuse that with larger fiscal deficits, necessarily.

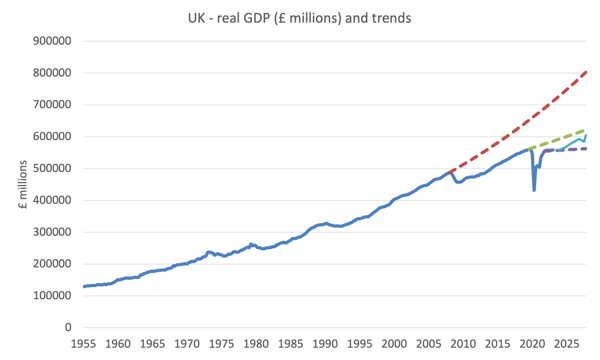

The following graph shows the real GDP for the UK from the March-quarter 1955 to the March-quarter 2023 in £ millions.

I then made four extrapolations out to the December-quarter 2027 to fit the UK Office for Budget Responsibility’s forecast horizon.

The dotted line starting at the March-quarter 2008 indicates what the UK economy would look like (in GDP terms) if the average quarterly growth rate up to then (0.63 per cent) had been maintained.

The dotted line starting at September-quarter 2019 indicates the trajectory had the average growth rate between the June-quarter 2008 and the September-quarter 2019 (0.31 per cent) had been maintained.

The dotted line beginning December-quarter 2021 indicates where the economy is heading if the average growth rate since the June-quarter 2022 (0.06 per cent)was maintained.

Finally the line between the previous two extrapolations represents the March 2023 (latest) OBR forecasts.

At present, the OBR is forecasting a 1.3 per cent output gap in 2023, a 1.2 per cent gap in 2024 and a 0.1 per gap in 2024.

The methodology that they use biases the output gaps downwards, meaning they estimate full capacity is reached well before it has actually occurred, meaning their ‘full employment’ unemployment rate is biased upwards.

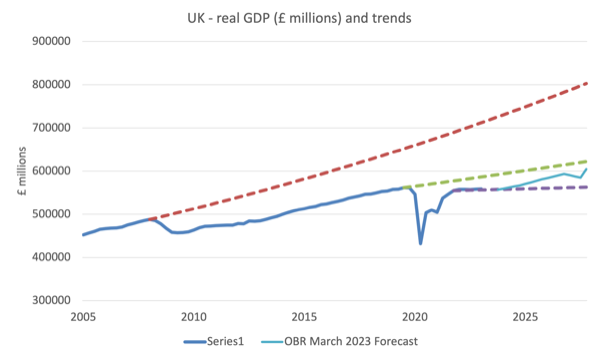

I have shortened the sample in the next graph to highlight the current situation.

Some extra calculations show that if the OBR are correct (and they won’t be) then the potential growth path is below the dotted line starting before the pandemic but well above the current growth path extrapolation.

In 2024, for example, the first year of a new national government in the UK, the spending shortfall implied by the OBR forecasts and imputed potential GDP will be of the order of £27,356.7 million falling to £2,304.4 million in 2025, if the aim is to achieve full capacity output (as defined by the OBR).

I actually think the spending gaps will be much larger than that but at any rate you see the point.

If the new Labour government in 2024 was speaking truly about wanting to provide jobs for all that desired to work then they will have to oversee a significant increase in spending in their first two years of office.

The question then is how close is the UK economy to full capacity.

There is no way the economy is at full capacity.

Further there are sectoral challenges that must be dealt with and over the weekend I read the – NHS Long Term Workforce Plan – which was released on June 30, 2023 but updated on July 11, 2023.

The NHS plan was requested by the government and involves strategies and estimates for training, retaining staff and reform processes to boost productivity.

It is a very detailed planning document that contains a massive amount of data and seeks to model the staffing that will be required to put the NHS on a “sustainable footing and improving patient care”.

They suggest that the current vacancy level is 112,000 in local services which “is a reflection of how the needs of our population have grown and changed, thanks in large part to the role better care and advances in medicine have played in increasing life-expectancy by 13 years since 1948.”

The ageing population will under current performance leave the NHS “with a shortfall of between 260,000 and 360,000 staff by 2036/37.”

The Plan is to among other things:

1. “Double the number of medical school training places, taking the total number of places up to 15,000 a year by 2031/3”.

2. “Increase the number of GP training places by 50% to 6,000 by 2031/32.”

3. “Increase adult nursing training places by 92%, taking the total number of places to nearly 38,000 by 2031/32.”

4. “Provide 22% of all training for clinical staff through apprenticeship routes by 2031/32, up from just 7% today.”

5. “Expand dentistry training places by 40% so that there are over 1,100 places by 2031/32.”

6. A whole host of career enhancement strategies and other organisations shifts.

If the Plan is to be realised then massive new outlays will be required.

The Plan estimates, for example, that £2.4 billions will be required through 2028/29 just to “fund the 27% expansion in training places.”

New infrastructure will be required at considerable £ investment.

Additional investment in the education sector to fund boosts to healthcare education and training will be required.

Further, and not to be forgotten, the Plan notes that “Health and care services are interdependent” and reform to the social care system will also be expensive.

Keir Starmer keeps claiming that his message is ‘reform not spending’ but the two are interdependent.

And the hole that the NHS finds itself in after more than a decade of austerity cuts is so large that the reforms will have to be scaled accordingly.

Then there is housing, social security (Starmer makes a big deal about ‘security’), education generally and more that have been devastated by the Tory neglect.

The question then is whether all this ‘reform’ with commensurate spending requirements can be achieved within the current available productive resource envelope?

This question is invariant to whether the private or public sector spends.

Even with the current likely output gaps persisting for some years, I doubt very much whether there is sufficient fiscal space – which I define as available productive resources that can be brought back into productive use by increased spending – to accomplish the required reforms with other policy initiatives.

And that raises the question of taxation!

There is no doubt that the new British government in 2024 will have to lift public spending if the reform agenda is to be realised.

I do not think the private market can deliver in the areas of most need – housing, health, education, social care, etc.

So Starmer is wrong to claim that increased spending will not be required.

Of course it will.

But the increased spending that will be required to redress some of the damage that the years of Tory rule have created and also to really reorient the British economy towards a low-carbon, more inclusive and fully employed state, will overwhelm the current resource availability.

There is no financial constraint on the British government lifting its nominal spending.

But it would hit the inflation-ceiling (exhaust available resources) before it had spent enough.

Conclusion

Which means that Starmer should also be outlining a plan to reduce the purchasing power of the non-government sector over time to balance total spending with available resources.

He doesn’t want to have that debate which is why he is claiming the future will not require higher spending by government.

He is wrong on the latter and that means he will have to confront the tax debate or simply deliver more austerity and pain.

Higher taxes will be required not to fund the spending commitments but to create the fiscal space.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2023 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.