Tomas Key

During the recovery from the Covid pandemic, the demand for workers rose to unprecedented levels in the UK. The number of jobs that firms were looking to fill increased to 1.3 million in the middle of 2022, 60% higher than the level in the past three months of 2019. The amount of job vacancies has fallen substantially over the past year, but remains at a high level. This post discusses how those changes to the demand for workers have affected the unemployment rate. In particular, it outlines how an equilibrium model of the labour market can help to explain why there appears to have been a change to the relationship between job vacancies and unemployment in recent years.

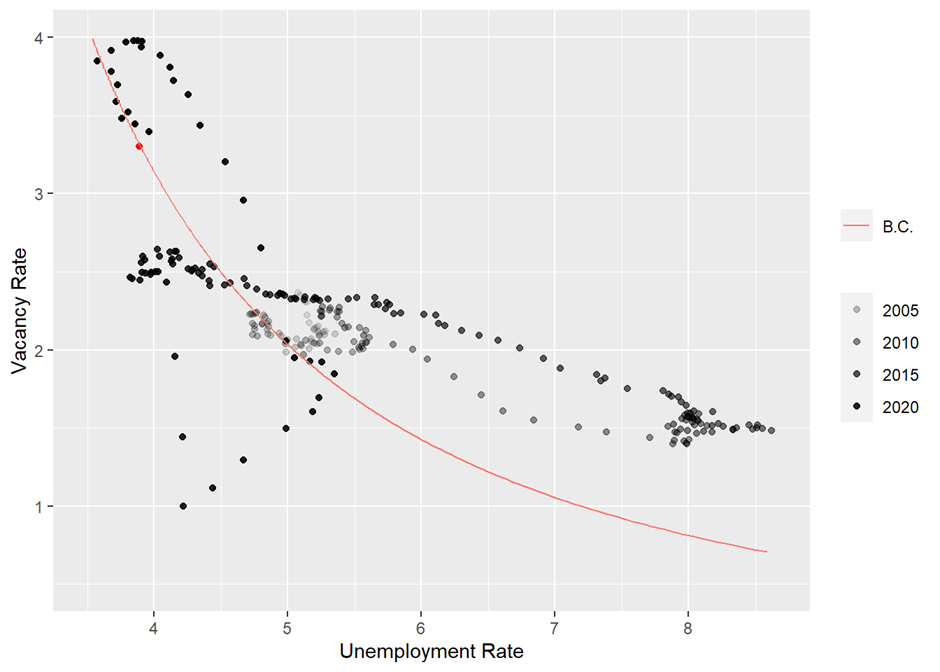

The Beveridge curve

Before turning to the model, let us first take a look at the data. In Figure 1, I have plotted the vacancy and unemployment rates that have been observed over the past 20 years or so. This shows the striking recent increase in the vacancy rate that I mentioned. It also shows that before the pandemic, there was a reasonably stable negative relationship between the vacancy and unemployment rates. When firms are looking to fill more positions, it is easier for unemployed workers to find a job, and so there tends to be fewer of them. This relationship is known as the Beveridge curve.

Figure 1: Vacancy and unemployment rates

Notes: Data is from the three months to June 2001 to the three months to April 2023: latest observation highlighted in red. Vacancy and unemployment rates are as a proportion of the labour force. I use unemployment and labour force data for those aged 16–64 to be consistent with the inputs to the modelling exercise.

Source: ONS.

Based on that pre-pandemic relationship, it would have been reasonable for a casual observer to expect that the very high vacancy rate in 2022 would have been accompanied by a much lower unemployment rate than was the case. Below, I will outline how a fairly standard model of the labour market can help to explain: (i) why the post-pandemic increase in the vacancy rate did not produce a lower unemployment rate; (ii) why the substantial fall in the vacancy rate over the past year has only been accompanied by a relatively modest increase in the unemployment rate; and (iii) the impact that a further decline in the vacancy rate is likely to have on the unemployment rate.

A model of the labour market

The framework that can be used to interpret labour market developments is based on the transitions – or flows – between employment, unemployment and ‘inactivity’ – a catch-all term for anyone that is not currently working or actively searching for work. Lots of people experience these transitions every quarter in the UK. For example, around a quarter of a million people moved from employment into unemployment in every quarter of 2022. Changes to the rate at which people are making these transitions are what generate movements in the employment, unemployment and inactivity rates.

At the heart of the model is an aggregate matching function. This is a device that is useful for summarising how the time that it takes to find a job – or match – is determined by the number of vacancies relative to the number of job seekers as well as the level of ‘matching efficiency’ – the productivity of the matching function. It captures the fact that it takes considerable time and effort for job seekers to find a suitable vacancy, and that this is affected by both the number of opportunities that are available and how many other people are competing to fill them.

The measure of job seekers that I use when estimating the matching function includes unemployed workers as well as some employed and inactive individuals. In the case of inactive people, that might seem odd as I mentioned above that these are individuals who report that they are not actively searching for work. However, many of them do move into employment over a three-month period, perhaps because their circumstances change or they are lucky enough to find a job without having to search for one. Accounting for these ‘passive’ job seekers among the inactive, as well as an estimate of the number of employed individuals searching for work, has been shown to be important in recent research.

After estimating the parameters of the matching function, I can use it to describe how the level of the vacancy rate affects the rate at which people transition into employment. When combined with values for the other flow rates – such as the rates at which individuals are entering unemployment from employment and inactivity – this gives a framework that can be used to trace out the impact of changes to the vacancy rate on the steady-state, or equilibrium, unemployment rate. That is the rate that is obtained once the system has fully adjusted to the changes in the flow rates.

Figure 2: Simulated relationships between the vacancy and unemployment rates

Source: Author’s calculations.

Two illustrations of this are shown in Figure 2. The model produces the negative relationship between the vacancy and unemployment rates seen in the data. That is due to the impact of the vacancy rate on the speed with which unemployed workers find jobs – their ‘job-finding rate’. Holding the other transition rates constant, a higher vacancy rate will raise the job-finding rate of unemployed workers, and so reduce unemployment. This figure also demonstrates that, in this framework, changes to the other flow rates or to matching efficiency will lead to a shift in the position of the simulated Beveridge curve. They will change the level of the unemployment rate that is produced by any level of the vacancy rate.

Another important feature of the simulated relationship between the vacancy and unemployment rates produced by the model is that it is non-linear, or convex. This reflects the fact that as the number of vacancies increases relative to the number of unemployed, it becomes increasingly difficult for firms to fill them. That is something that many companies in the UK have become familiar with in recent years.

Explaining recent labour market dynamics

It is now time to bring together the simulated relationship between the vacancy and unemployment rates produced by the model and the data. I have done that in Figure 3. The simulated Beveridge curve on this plot is produced by the framework I described when calibrated with flow rate estimates from the past year – it is not an attempt to fit a curve using all of the data shown on the chart. The fact that the simulated Beveridge curve does not fit through all of the data makes clear that the changes in the unemployment rate that have been seen over time have not only been due to the impact of changes in the vacancy rate. They have also been due to changes to other flow rates, such as the rate at which people are moving from employment to unemployment, and to matching efficiency – factors that act to shift the position of the curve produced by the framework that I have described.

Figure 3: Simulated Beveridge curve and vacancy and unemployment rates

Notes: Data is from the three months to June 2001 to the three months to April 2023: latest observation highlighted in red. Vacancy and unemployment rates are as a proportion of the labour force. Simulated Beveridge curve is produced using data from 2022 Q1 to 2023 Q1. Data on labour market stocks and flows is for those aged 16–64.

Sources: Author’s calculations and ONS.

So how can this help to explain recent developments? Well, over the past year or so, changes in the vacancy rate have been the main factor generating changes in the unemployment rate. That means that the data have moved down the simulated Beveridge curve. As the vacancy rate is currently very high relative to the unemployment rate, the portion of the curve along which the data have moved is relatively steep. That is why the substantial fall in the vacancy rate over the past year has only been accompanied by a fairly modest increase in the unemployment rate.

The reason that the very high level of the vacancy rate in 2022 did not produce a lower unemployment rate reflects two factors. First, the steepness of the curve that I just mentioned. Second, the fact that the simulated Beveridge curve has ‘shifted out’ from its position before the pandemic. The reason for that shift is that there has been both an increase in flows from inactivity into unemployment, which act to increase unemployment for any level of the vacancy rate, and a reduction in matching efficiency.

The impact of further falls in the vacancy rate will depend on whether the data continue to move down a stable Beveridge curve, or the curve shifts position once more. The current position of the curve suggests that the unemployment rate might settle at a level higher than immediately before the pandemic, once the demand for workers has returned to a more normal level.

Conclusion

Although some recent movements in the UK vacancy and unemployment rates appear odd at first glance, they can be well-explained by a standard model of the labour market. That framework also provides some guidance about the future direction of the labour market – about the impact of further falls in the vacancy rate on the unemployment rate. That impact will depend on whether the data continue to move down a stable Beveridge curve, or whether changes to matching efficiency or to other features of the labour market lead to a deviation from that path.

Tomas Key works in the Bank’s Structural Economics Division.

If you want to get in touch, please email us at bankunderground@bankofengland.co.uk or leave a comment below.

Comments will only appear once approved by a moderator, and are only published where a full name is supplied. Bank Underground is a blog for Bank of England staff to share views that challenge – or support – prevailing policy orthodoxies. The views expressed here are those of the authors, and are not necessarily those of the Bank of England, or its policy committees.

Share the post “How have recent changes to the demand for workers affected the unemployment rate?”