On Friday (July 29, 2023), the Australian Bureau of Statistics released the latest – Retail Trade, Australia – data, which showed that total retail turnover fell by 0.8 per cent in June 2023 and was up 2.3 per cent on June 2022. In May 2023, it was up 4.1 per cent. So things have slowed. Almost all the components (Household goods, Clothing etc, Department stores, Cafes etc) were down on the month. The ABS noted that despite the massive EOFY sales, “retail turnover fell sharply … as cost-of-living pressures continued to weight on consumer spending”. By way of contrast, in the US the June data from the US Census Bureau – Advance Monthly Sales for Retail and Food Services (released July 18, 2023) – shows up 0.2 per cent in June. Moroever, the latest University of Michigan Survey of Consumer Sentiment results – Improving personal finances, business conditions lift consumer sentiment (released July 28, 2023) – reveal a sharp increase in consumer sentiment in the US. But there was a twist, which is the point of this post. The Survey reported “the material improvement in the economic experiences of consumers relative to the peak of high inflation last year … with the notable exception of lower-income consumers, who anticipate continued challenges from inflation and a potential weakening in labor market prospects.” What we will discuss today is that central bankers are effectively intent on increasing poverty in their societies. And, whichever way one looks at it, relying on such a pernicious policy tool – one that deliberately seeks to increase poverty – is not a sound basis for achieving social stability. And, and as inflation has been falling anyway, despite the hikes, the negative distributional impacts should militate against using such a nasty and inefficient instrument.

The question I get asked regular in radio interviews and off-the-record discussions with journalists is why hasn’t the US economy tanked given the ongoing interest rate hikes by the US Federal Reserve and why is the Australian economy slowing quickly when the RBA hasn’t hiked as much and was later to the party?

I provided some guidance as to why interest rate changes may impact differentially in the US and Australia this blog post – RBA governor’s ‘Qu’ils mangent de la brioche’ moments of disdain (June 8, 2023).

I noted several factors that influence the response to interest rate increases.

First, no-one really knows whether the winners from the interest rate rises will spend more than the losers cut back spending.

The evidence is that wealth effects on consumption spending are relatively low when compared to the income effects.

But there are many complications – such as saving buffers etc – that make it hard to be definitive.

Second, in the immediate period after the interest rate rises, the spending responses from debtors is likely to be restrained because they have capacity to absorb the squeeze by adjusting their wealth portfolios (run down savings etc).

Thus, the interest rate rises are likely to be inflationary as businesses pass on their increased borrowing costs in the form of higher prices, and, as noted above, landlords pass on their higher mortgage servicing costs as higher rents, which, in turn, feed into the CPI figure.

Third, in the medium- to longer term, if interest rate rises move past some threshold, the impact is to slow spending and increase unemployment.

Eventually, those who benefit from the interest rate increases, who typically have a lower marginal propensity to consume (how much they spend out of every extra $ received), run out of things to buy and pocket the bonuses.

And eventually, the spending cuts from the debtors, particularly lower income mortgage holders, begins to dominate.

To make assessments then, we have to take into account:

1. The level of household debt – the higher the debt, the more the negative impacts of the interest rate rises will be on spending.

2. The proportion of population that has mortgage debt – the higher the proportion the more likely it is that the medium- to longer-term effects will become dominant.

3. Crucially, the proportion of mortgage debt that is fixed rate compared to variable rate.

In the US, while the debt levels are relatively high by historical standards, the outstanding mortgages are mostly fixed rate over long durations and held by those further up the income distribution, which means that the rising interest rates are less likely to cause major spending cutbacks from mortgage holders.

Then the higher incomes that the wealth holders gain from the Federal Reserve rate hikes dominate.

In Australia (and other nations in Europe, the UK, Canada etc) where the vast majority of mortgages are variable rate and more likely to be held by low-income families, then the rising mortgage payments will squeeze disposable income and ultimately a bust occurs.

These insights focus our assessments of the conduct of monetary policy on distributional matters, which is why I consulted the latest University of Michigan Survey data last week.

I wrote about the distributional impacts of monetary policy in these blog posts among others:

1. Monetary policy in the hands of the central banker sociopaths is advancing the class interests of the elites (July 5, 2023).

2. RBA is engineering one of the largest cuts to real disposable income per capita in our history (March 8, 2023).

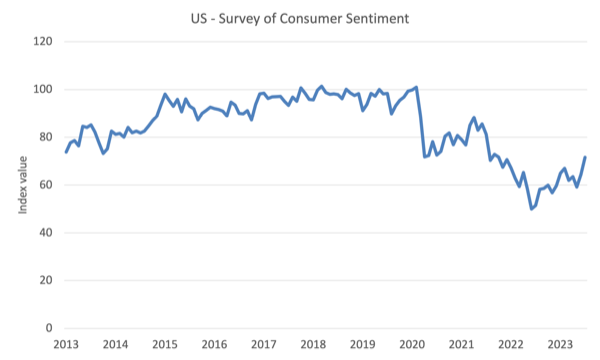

The latest US Survey of Consumer Sentiment reveals a result that is back around the October 2021 level and has risen sharply in the recent months.

In June 2022, the index stood at 50 and it is now at 71.6 points.

It rose from 64.4 to 71.6 index points between June and July 2023 – an 11.2 per cent increase (one of the largest monthly increases in the history of the index).

The following graph shows the evolution of the index since January 2013 to July 2023.

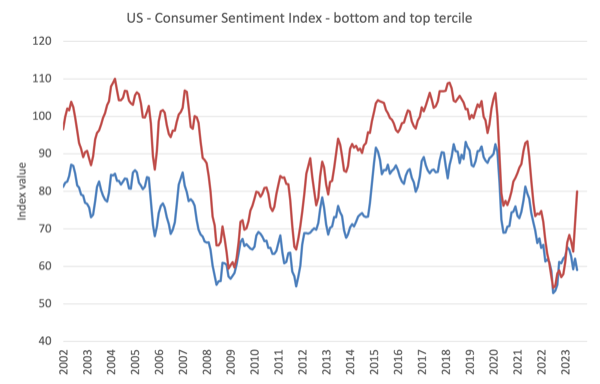

But, the latest Survey data shows a marked difference in fortunes for the top income tercile relative to the bottom, which helps to explain why retail behaviour is different in Australia and the US.

It also allows us to understand why monetary policy is an ill-advised macroeconomic policy tool.

A tercile is generated when a dataset is divided into three equal parts – bottom third, middle third, and top third.

The following graph shows the evolution of the Survey from 2002 to July 2023 for the top and bottom tercile groups

After a period of rising sentiment for both groups, the index is now falling for the low-income consumers but rising sharply for the top-tercile consumers.

The Federal Reserve Bank like most central banks (the Bank of Japan being the notable exception) have sought to quell inflationary pressures by hiking interest rates.

Their stated aim is to increase unemployment because they think that will douse the inflation, despite the obvious fact that inflation is falling rapidly as the supply-side factors abate.

Those factors are not abating because of interest rate increases but, rather, because the world is adjusting somewhat to the Covid, Putin and recent OPEC shocks.

We also know that when unemployment rises it impacts on the low-income workers disproportionately – they are typically the first to go and the last to be hired again.

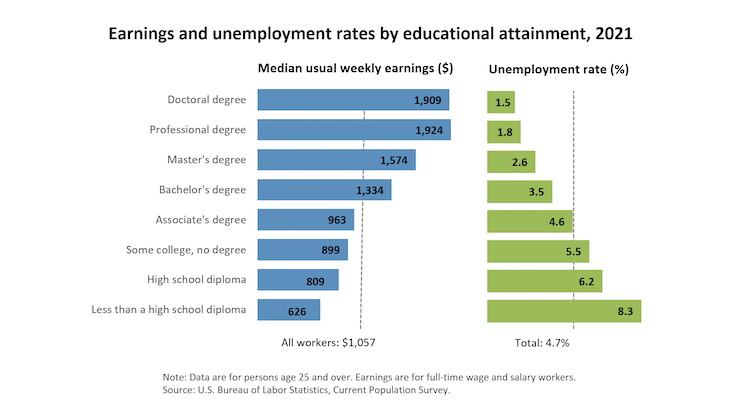

The following graph produced by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics shows the link between education, earnings and unemployment (in 2021).

There is a huge disparity between the unemployment rates by income cohort, even when the aggregate unemployment rate is fairly low (4.7 per cent in 2021)

And in the US that disproportionately spreads to ethnic groups (African American fare the worse).

And, there is a direct positive link between unemployment and poverty incidence.

So, in effect, the Federal Reserve and the rest of the central bankers who are hiking rates, are intent of causing rising poverty rates among the most disadvantaged workers in the community.

They don’t express it like that – but that is what they are doing.

For now, unemployment rates have not risen much – but they will if the rates continue to rise.

For now, what we observe is:

1. The higher income consumers who also are less likely to be impacted by any unemployment and have much higher discretionary spending capacity, which gives them greate scope to adjust to inflationary pressures without comprosing living standards much are feeling very confident.

2. This group also is receiving massive income boosts because they are more likely to hold financial assets and their mortgages are mostly fixed rate.

3. Alternatively, the lower income consumers have much less to zero discretionary spending capacity and are thus hit harder by the inflationary pressures, particularly as a high proportion of their incomes is spent on food and energy.

4. While they have less likely in the US to have large mortgages they are more likely to become unemployed and have low saving buffers (if any).

5. It is thus little wonder that their consumer sentiments will fall now as the Federal Reserve continues its obsessive rate hikes.

The unemployment fear for that group is rising even as inflation is falling.

Conclusion

Trying to work out what the impacts of rising interest rates will be involves a deeper analysis of the distributional impacts of the hikes.

And central bankers are as unclear of the net effects of their actions as anyone.

Borrowers are hurt, creditors gain.

Those who hold financial assets gain, those with little wealth are hurt.

The net impact depends on a number of factors as outlined above.

It is obvious that the rate hikes have not yet caused recessionary conditions to emerge and that is probably because the winners from the hikes are still spending freely on the basis of their wealth gains, while the lower-income groups are cutting back but not to the same extent.

Eventually, if the rate hikes continue, there will be a rise in unemployment as the spending of the wealthy will reach saturation point.

The declining inflation rates are also helping because the cost-of-living pressures on the poorest families are easing a bit.

In the US, the poorest are less likely to have mortgages so for them the threat from the rate hikes is rising unemployment.

In Australia, low-income families have a higher proportion of mortgages than in the US and they are more likely to be variable rate loans.

That is why the impacts of the hikes are looking to be more severe in aggregate terms.

But whichever way one looks at it, relying on such a pernicious policy tool – one that deliberately seeks to increase poverty – is not a sound basis for achieving social stability.

And, and as inflation has been falling anyway, despite the hikes, the negative distributional impacts should militate against using such a nasty and inefficient instrument.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2023 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.