Your weekly Interpreter feature about issues, resources

or helpful distractions that might otherwise be missed.

We’re asking contributors to put together their own collected observations like this one – and as always, if you’ve got an idea to pitch for The Interpreter, drop a line via the contact details on the About page.

Nothing is as it seems in Australia’s closest neighbour, Papua New Guinea. Just last month the United Nations Population Fund revised down its estimate of PNG’s population from 17 million to 11.8 million, which finally sits comfortably with the PNG government. That’s a walloping 5.2 million revision by the UN. And even then, no one really knows the exact number of people in the country.

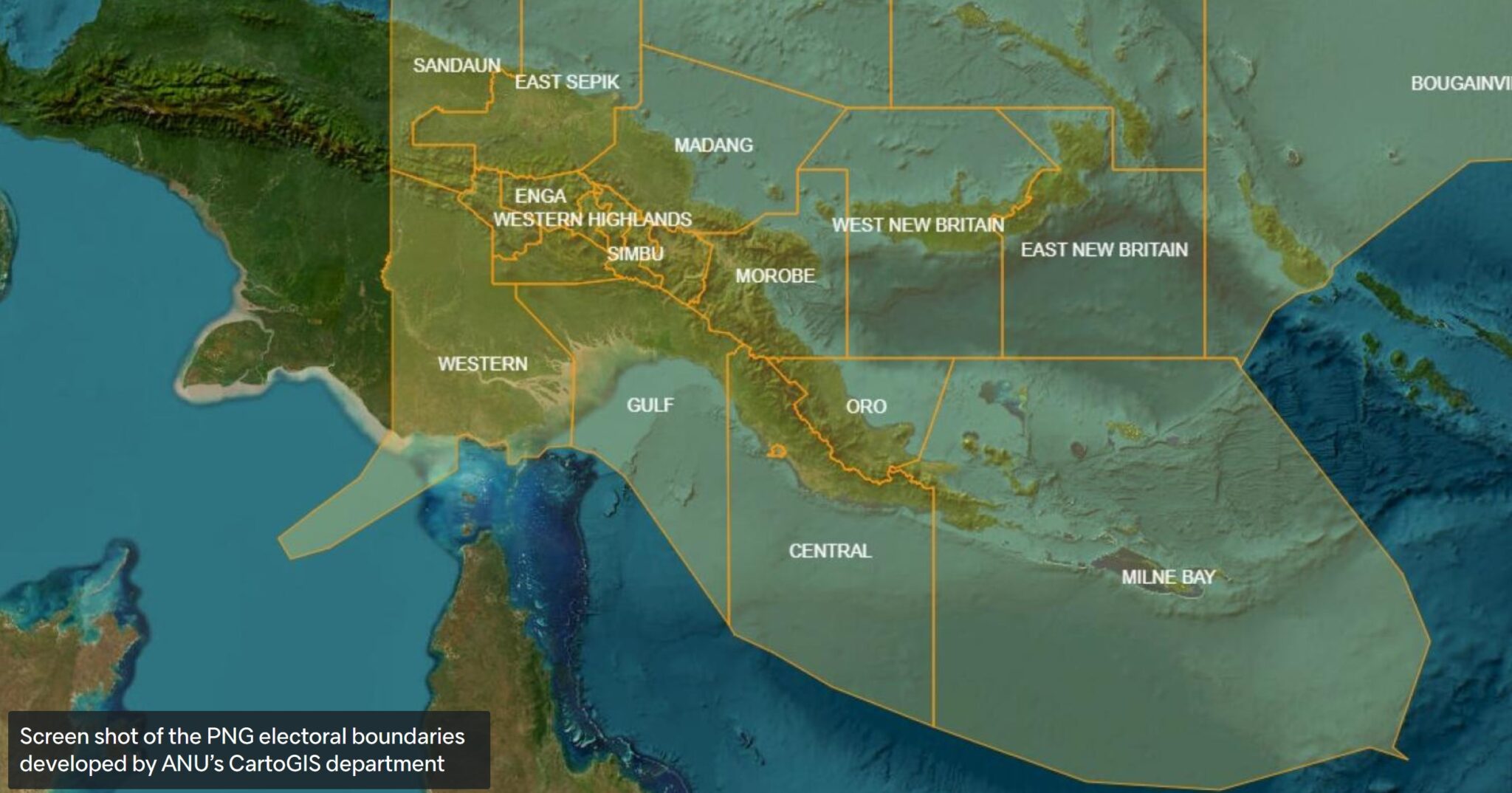

Another contentious issue is mapping. Before the elections last year, PNG rushed through seven new voting districts. Although the Electoral Commission released new district maps individually, it failed to publish a new national map. Now, thanks to the Australian National University’s CartoGIS department, we have a map that reveals an estimated size of the new districts.

As geopolitical competition over PNG grows, so must the accuracy of knowledge about the country.

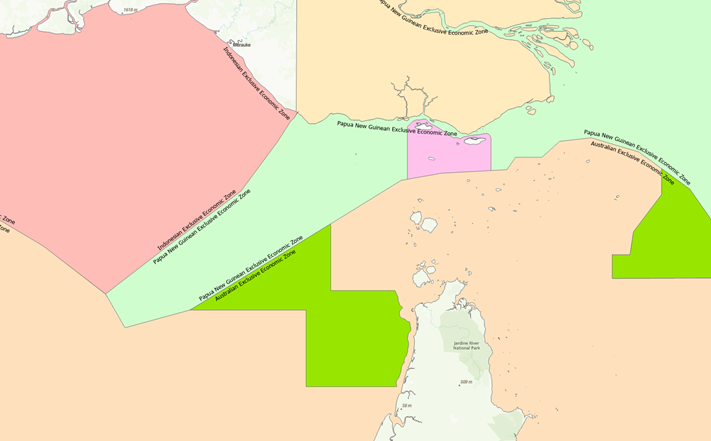

The map itself has a few quirks. PNG’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) is drawn weirdly – particularly in the south-west where PNG shares maritime borders with Australia and Indonesia.

Generally, EEZ boundaries are defined as up to a 200 nautical mile buffer from a nation’s territorial sea. According to this map, PNG owns a strip of ocean jutting out well into what might be considered Australian and Indonesian territory. This appears not to be a fault of PNG, but a consequence of how Australia and Indonesia’s EEZs and marine parks are drawn.

Finding an accurate map is important, particularly concerning security as Australia and the United States work toward security pacts with PNG. The United States signed a defence cooperation agreement with PNG in May, and Australia is close to putting pen to paper on one with PNG as well. PNG is courting other nations, too, with Narendra Modi (India), Joko Widodo (Indonesia), and Emmanuel Macron (France) all visiting Port Moresby in quick succession.

As geopolitical competition over PNG grows, so must the accuracy of knowledge about the country. Otherwise, all assessments will be founded on guesswork.

Work on both the PNG–China and PNG–Australia FTAs is in the early stages. Following a feasibility study comes consultations with relevant stakeholders and negotiations between respective governments, which can take a long time – although PNG’s Prime Minister James Marape intends to complete the China FTA at the “very earliest” opportunity. Work on the FTAs faces a political risk as well – if Marape is removed as PM when votes of no confidence are allowed in 2024, a new government may choose to delay or end work done on any of the free trade deals.

That said, for PNG, these trade agreements bring a positive shift in policy, forcing government out of the protectionist regime it has adopted in recent years. Between 2018 and 2019, PNG introduced 323 tariff line increases to assist local manufacturing companies and raise government revenue, reversing a 20-year tariff reduction program (TRP).

The tariffs and levies have contributed little to government coffers, failing to exceed 3% of government revenue since 2018.

PNG has three tariff categories: intermediate, protective, and prohibitive. Intermediate rates are applied to inputs used in the production processes of local industries. Protective rates are imposed on imports of final goods that compete with domestic producers. Prohibitive rates are the highest category of tariffs, applied to goods deemed valuable exports.

The TRP reduced tariff rates at three-year intervals beginning in 1999. The target in 2019 was for intermediate tariffs to reach 10% from an average of 30%; for protective rates to reach 10% from an average of 49%; and for prohibitive rates to reach 25% from rates above 55%. By 2015, intermediate, protective and prohibitive rates had reached 10, 15, and 30% respectively.

Tariff hikes in 2018 and 2019 raised rates by an average of 7% and 14% respectively. The PNG government further introduced levy and fee increases on imported oil palm machinery in 2020.

The tariffs and levies have contributed little to government coffers, failing to exceed 3% of government revenue since 2018. Further, these tariff hikes may not assist manufacturers as intended. While a study on the effectiveness of the 2018 and 2019 tariffs hasn’t been conducted, a tariff study in 2003 found that the manufacturing sector, then protected by high tariffs, expanded the slowest. High tariffs also negatively affected export industries by raising costs on imported inputs and punishing large capital-intensive producers.

The FTAs will be at odds with Marape’s other policies to encourage import substitution. For instance, in promoting timber processing, government increased the export tax on round logs by 20% this year. This follows the 2020 export tax rate increase from 32.5 to 59% on round logs which drove several logging companies out of business and led to a fall in log exports. In addition, government has announced a ban on round log exports in 2025, although similar promises in the past have not been kept.

Overall, FTAs with both Australia and China are welcome as they will lead to better development outcomes for Papua New Guineans and encourage PNG to revisit policies that have been detrimental to trade. In the years to come, however, an FTA with China will likely make the superpower PNG’s most important trade partner.

Contributor: Maholopa (Maho) Laveil.