I am in the final stages of moving office and it has been a time consuming process. And one of my regular research colleague, Professor Scott Baum from Griffith University, who occassionally provides blog posts here, sent me some research which he had written up in blog post form and with time short today, here is Scott’s latest guest spot. Today he is going to talk about a new analysis of financial insecurity that we are currently doing.

So in Scott’s words …

Despite what the neo-liberals think, there is no financial buffer for many Australian communities

Over the past 12 months or so, the neo-liberals have been keen on telling us that as a result of the restrictions imposed during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, Australian households built up a significant financial buffer largely in the form of savings deposits.

When the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) began jacking up interest rates, the RBA Board claimed (Source):

Some households had substantial savings buffers … households would be willing to reduce current saving rates or draw down on extra savings accumulated during the pandemic to cushion consumption from the effects of declining real incomes; these accumulated buffers represented a larger share of household income in Australia than those remaining in many economies.

A similar message was shared in an article published in the RBA Bulletin (June 16, 2022) – Household Liquidity Buffers and Financial Stress:

The ratio of household liquid assets to household income in Australia has increased substantially over recent decades, at both the aggregate and individual household levels. The increase in buffers has been most pronounced for households with mortgage debt and among indebted households – with those with the most debt typically holding the highest liquidity buffers. This is important from a financial stability perspective as liquidity buffers allow households to smooth their spending and maintain their debt payment obligations in the event of adverse shocks to their cash flows; as such, they are a key factor in reducing household financial stress.

So the RBA was trying to tell us not to worry about rising prices, housing costs and other things because we all can just use our saving buffers.

In aggregate, this all sounds fine.

But aggregates are problematic.

They hide the significant heterogeneity in social and economic outcomes.

Consider the results from surveys such as this – Taking the Pulse of the Nation report (published May 2023).

The Report states that:

Despite better employment, Australians continue to face increasing costs, resulting in shortage of funding to cover basic needs such as food, housing, and health expenditures. Vulnerability has not decreased in the past six months. Treating eating enough, eating nutritious foods, ability to pay utility bills, and addressing health needs as four separate challenges that leads to financial vulnerability, 15 percent of the population reported one challenge and 34 percent of the population reported two or more of these challenges.

And that:

Over the past six months (August 2022 to February 2023), financial stress has increased slightly. Today, more than half (53 percent) of Australians report just making ends meet or worse.

So despite the aggregates spruiked by many, there are a significant number of people suffering from financial stress who are in danger of falling through the cracks.

Financial insecurity …coming to a suburb near you!

In one of the subjects I currently teach, we often have wide-ranging discussions about how current social issues are played out across different cities and communities.

Not surprisingly, given the current state of play, my students often turn to the subject of the cost of living and financial (in)security, especially as many of them are living away from home for the first time or have moved to Australia from overseas and are attempting to eke out an existence with little financial backing.

The topic of financial insecurity was fitting, given the students are currently focusing on issues of social and economic disadvantage, and it was interesting to see them unpacking some of the issues.

Following on from the classroom discussion, I decided to experiment with a measure of financial insecurity to complement the other indices that Bill and I have worked on over the years.

For those interested, our – Employment Vulnerability Index – and the – Index of Prosperity and Distress in Australian Localities – measure employment vulnerability and economic prosperity at the level of a Statistical Area 2 (SA2), and you can explore the data via the links.

In major cities, SA2s are akin to suburbs or other large communities, so they make a good level of aggregation to work with.

The idea was to develop an index that identifies the geographic distribution of financial insecurity across suburbs and other places.

We will release an in-depth report in due course, but the initial scan of the results shows some interesting outcomes.

The index borrows ideas from a 2022 research article – A Multidimensional Approach to Measuring Economic Insecurity: The Case of Chile – which was published in the journal Social Indicators Research and focuses on developing ways of measuring economic insecurity.

The author defines financial insecurity as:

The adverse well-being effect of involuntary exposure to uncertainty in enduring an uninsured financial shortfall.

The author also notes that:

The idea behind it is that economic insecurity has a subjective component and is a forward-looking measure since stress and anxiety are associated with financial uncertainty.

They suggest that financial insecurity can be measured by accounting for two dimensions:

The first dimension is the risk of the household experiencing potential events related to negative economic consequences such as unemployment, losses in asset values, or unexpected medical expenses …

The second dimension is the lack of household economic buffers, which generates stress such as not having enough assets to face an event that decreases incomes or increases expenses, or not having access to social protection mechanisms to offset these economic losses.

There is an interesting collection of data available, with the minimum requirements being:

- Being a reasonable measure or proxy of one of the dimensions and

- Being available at a usable aggregate spatial level.

The first dimension can be measured by the percentage of people in an SA2 who derive their income from government payments or the percentage of households classified as facing mortgage or rental stress.

The second dimension can be measured by considering the dollar amount of per person bank interest received and the amount of dividend income received, the per person wage and salary, the percentage of people who say they can’t afford a night out, and the percentage of people who do not have access to emergency funds.

The main take-home from the initial first-cut analysis is financial insecurity is heavily concentrated in communities that are highly disadvantaged.

No surprises here.

As usual, those suffering the most in social and economic terms continue to be screwed.

But it is not only the most disadvantaged who are under the pump.

The analysis also shows that there is another tier of places that are classified as suffering extreme financial insecurity.

These places are not those often considered as facing serious disadvantage but given their level of financial insecurity, are places likely to be facing mounting pressure.

A caveat to the research is that the data does not account for the most recent period of extreme price rises so we can imagine that the position of both groups of places has been magnified.

The results for Sydney (Australia) provide a good illustration.

If we compare the outcome of our financial insecurity index and the Australian Bureau of Statistics SEIFA index of relative disadvantage, we can see some patterns emerge.

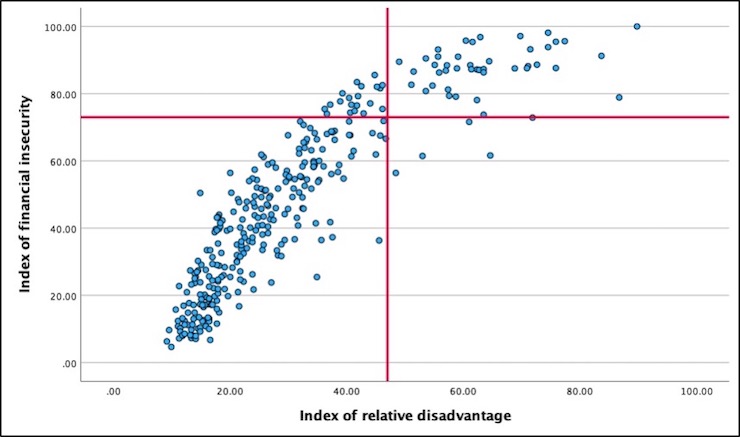

The scatterplot represents SA2s at various points on a high-to-low continuum with those above the line on the y-axis representing the most financial insecurity and those to the right of the line on the x-axis representing most relative disadvantage.

Quadrant two represents the group of SA2s with both high relative disadvantage and high financial insecurity. Quadrant 1 represents those SA2s which, while not among the most disadvantaged, are still counted among places suffering from high levels of financial insecurity.

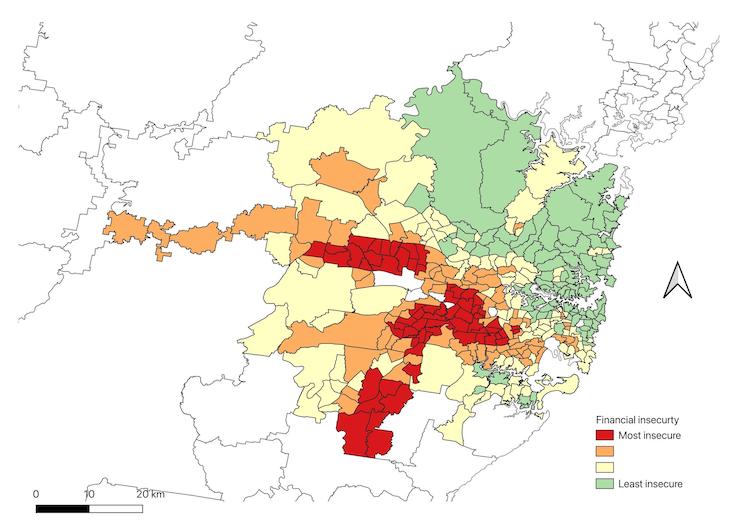

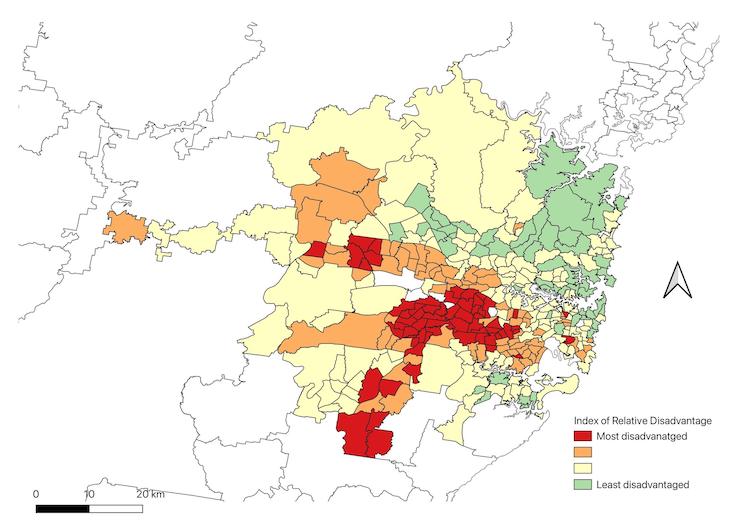

The two maps illustrate the spatial distribution across Sydney of the two measures.

The first is the measure of financial insecurity, while the seonc is the ABS SEIFA measure.

The distributions are relatively clear.

Clusters (or hot-spots) of SA2s in the west and southwest of the city are classified as being highly disadvantaged, and larger clusters of places in the same regions are classified as suffering high levels of financial insecurity.

Financial insecurity: One more aspect of community demise

Financial insecurity is a gauge of future community demise.

For those communities facing serious financial insecurity, even a small shock will have significant and wide-ranging implications.

If we borrow from the literature on resilience, we would say that financial insecurity is a measure of the ability of individuals, households and communities to be able to withstand shocks and bounce back.

Bill and I currently have a large Australian Research Council grant which is looking at the resilience of regions to bounce back due to economic shocks.

An index of financial insecurity adds a smaller-scale component to that work.

The level of resilience in terms of financial security is being tested in communities across the country and should be a further wake-up call for governments to do more.

The spatial concentrations of financial insecurity we are uncovering should be especially concerning.

We have pointed this out in some of our other work:

1. People, Space and Place: a Multidimensional Analysis of Unemployment in Metropolitan Labour Markets (published in Geographical Research on January 28, 2010).

2. Happy People in Mixed-up Places: The Association between the Degree and Type of Local Socioeconomic Mix and Expressions of Neighbourhood Satisfaction (published in Urban Studies on December 7, 2009).

–Self-assessed health status and neighborhood context (published in the Journal of Prevention and Intervention in the Community on August 11, 2016).

The concentration of disadvantage across vast parts of cities, towns or regions has a range of knock-on effects for people who live there, which push many further into the abyss of disadvantage.

Financial insecurity makes this worse.

But things seem to just keep going in the same direction.

We have a central bank that has lost the plot about dealing with inflation and we have governments who are unwilling to introduce meaningful, sustainable measures to deal with the pressures on families and households.

The government and others appear unwilling to accept that their decisions are likely to further disadvantage already struggling communities and threaten to plunge others into hardship.

They can only talk about undertaking responsible measures to relieve pressures on households, which seems to be code for giving very little to those who are most in need.

We have said this time and time again.

Conclusion

Our most disadvantaged deserve a better go.

The government could do something meaningful.

Something that would translate into a just and sustainable transition for our society and economy.

Instead, they seem to sit on their hands and maintain the status quo.

Not good!

We can do better!

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2023 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.