Yesterday, the – Flash Germany PMI – was released, which shows that “German business activity” has fallen “at fastest rate since May 2020”. Also released was the – Flash Eurozone PMI – which revealed that “Eurozone business activity contracted at an accelerating pace in August as the region’s downturn spread further from manufacturing to services”, Europe is heading to recession or should I rather say – stagflation – because the unemployment will rise sharply while inflatino is still at elevated levels. All because the policy settings are wilfully and unnecessarily driving nations into recession. Over the Channel, Britain is going through a similar experience – inflation is falling rapidly and the economy is plunging towards recession. The common link is the policy folly. The European Central Bank and the Bank of England have been increasing interest rates as a ‘chasing shadows’ exercise – meaning that the drivers of the inflation they claim to be fighting are not sensitive to the interest rate changes. But the interest rate hikes are causing damage to the real economy by increasing borrowing costs. Meanwhile, fiscal policy is in retreat because the government thinks it has to set policy to complement the central bank hikes – meaning two sources of austerity. And for those commentators who pine for re-entry to the EU – they should look East and see what a mess the European economy is in!

Recession in Europe

The contraction now evident in Germany is quite stunning.

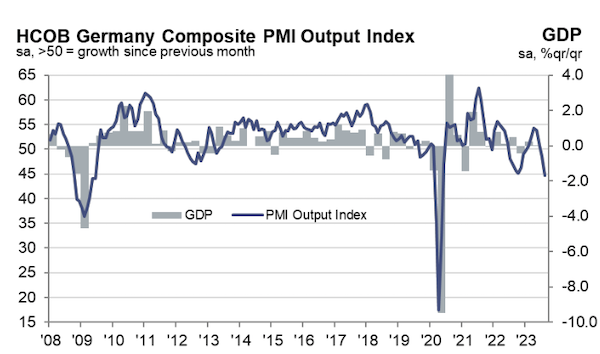

The German Composite PMI Output Index captures the results of the Manufacturing Output Index and the Services Business Activity Index.

Here is the Composite PMI since 2008.

A value below 50 indicates that more businesses are contracting than expanding.

The latest value shows the index fell from 48.5 to 44.7, the fourth consecutive month of decline.

Both the manufacturing and services sector went further into the sub-50 area of the index.

You can also see how well the Composite index predicts shifts in GDP.

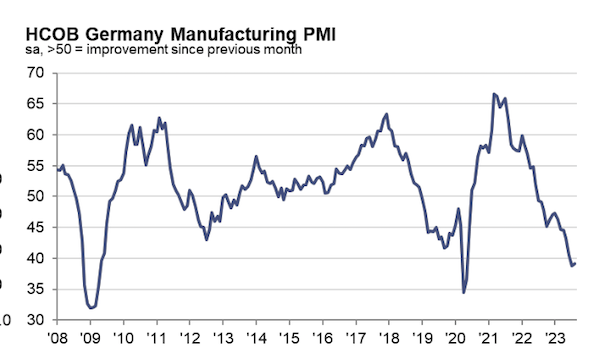

The German Manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) is derived from a survey of around 800 German companies and has a solid track record in “providing the most up-to-date possible indication of what is really happening in the private sector economy.”

Manufacturing PMI is “a composite index” which means it is compiled from five survey variables – new orders (weighted 0.3); output (0.25); employment (0.2); suppliers’ delivery times (0.15); and stocks of materials purchased (0.1).

It provides answers to the question: “Is the level of production/output at your company higher, the same or lower than one month ago?”

The next graph shows the manufacturing PMI.

The PMI Report say that the “decline continued to be led by plummeting manufacturing new orders” accompanied by a run down of inventories and “investment reticence”

The Index was at 39.1 in August – well below the 50-level turning point.

The commentary said that:

Any hope that the service sector might rescue the German economy has evaporated. Instead, the service sector is about to join the recession in manufacturing, which looks to have started in the second quarter.

So deeper into recession.

As the largest economy, what happens in Germany significantly influences what happens in the broader Eurozone.

And the Eurozone PMI data out yesterday confirms that.

The report said that:

… the region’s downturn spread further from manufacturing to services. Both sectors reported falling output and new orders, albeit with the goods-producing sector registering by far the sharper rates of decline. Hiring came close to stalling as companies grew more reluctant to expand capacity in the face of deteriorating demand and gloomier prospects for the year ahead, the latter sliding to the lowest seen so far this year … inflationary pressures continued to run far lower than seen over much of the past two-and-a-half years, led by falling manufacturing prices …

So there it is – the classic policy overreach.

Inflation has been falling since the third-quarter 2022 because the factors driving it were temporary – pandemic, Ukraine bottlenecks, and OPEC+.

Much of that supply turmoil has abated.

Sure enough Putin is still causing havoc but the supply shortages (particularly in terms of grains etc) as a result of his blockades have seen nations find other markets and so the supply constraints have eased.

The problem though is that once the pessimism sets in – as final retailers etc see rising unsold inventory, which then transmits to lower order rates to factories, then cut backs in production and hours of work, then cut backs in overall employment, then reduced investment in new plant etc, then multiplied declines in final sales – and the cycle continues – it becomes very hard to arrest it.

And that is especially the case if fiscal and monetary policy are working to create and reinforce the downturn.

UK heading the same way

On August 16, 2023, the British Office of National Statistics (ONS) released the latest – Consumer price inflation, UK: July 2023 – data, which showed that the UK inflation rate is declining sharply – from 7.3 per cent in June to 6.4 per cent in July.

In July 2023, the CPI fell by 0.3 per cent, whereas this time last year it rose 0.6 per cent over the month.

The UK inflation rate fell sharply mostly because the Office of Gas and Electricity Markets (Ofgem) Energy price cap was marked down significantly – from £3,280 to £2,074 or a 36.7 per cent drop.

Ofgem is thw UK energy regulator.

The price cap determines the price that many British households pay for gas and electricity.

It led to a 25.2 per cent decline in gas prices in the month – “the highest recorded fall in the price of gas since the series began in 1988 and meant that gas provided a downward contribution of 0.44 percentage points to the monthly change in the CPIH annual rate.”

Electricity prices fell by 8.6 per cent in July providing further downward pressure on the overall CPI inflation rate.

Neither factor has anything to do with excessive spending in the economy and neither is particularly sensitive to the Bank of England interest rate changes.

These supply factors have been transitory and are now resolving somewhat.

The other interest aspect to the July CPI data for Britain, which resonates in other nations that have been hiking interest rates, is the rapid rise in the contribution to the overall CPI result from housing rents.

For Britain, they rose 1.7 per cent on the month “compared with a 0.8 per cent rise between the same two months a year ago”.

This is an example of an administered price – where the government sets to rent.

I say that because the ONS tell us that the rising contribution from rents “was mostly from registered social landlord rents.”

Once again this is not interest-rate sensitive and reflects government fiscal policy settings.

And as inflation is falling, the policy settings are driving the economy towards or into recession.

Earlier this week (August 22, 2023), we learned via the Confederation of British Industry’s Monthly Snapshot of Manufacturing that UK factory production was no at its weakest level since 2020, when the country was first forced into closure due to Covid-19.

The CBI’s ‘net balance’ indicator – the difference between the share of factories reporting increased output and those reporting contraction – moved from +3 to -19 in July – a reading not seen since September 2020.

In the three months to August 2023, 37 per cent of the survey sample reported declining output levels and only 18 per cent reported rising production.

Production declined in 15 of the 17 sectors surveyed in the last quarter.

New orders slumped from -9 to -15.

The export market had weakened considerably – in no small part to the rapid contraction in Europe reported above.

But the survey also revealed that cost pressures were easing – it’s measure of price expectations fell to its lowest level since February 2021.

So while inflation is in decline, the policy settings are now creating a new problem – lost incomes and rising unemployment.

The CBI information is consistent with the message from the – Flash United Kingdom PMI – which was released yesterday (August 23, 2023).

It showed that:

UK private sector output falls at fastest rate since January 2021

The Survey data reveals that new orders have stalled, in part, because of “higher borrowing costs led to caution” – so an example of the impact of the interest rate hikes.

The data confirms that “inflationary pressures continued to moderate” as input costs declined sharply (energy etc).

The spokesperson said that “A renewed contraction of the economy already looks inevitable, as an increasingly severe manufacturing downturn is accompanied by a further faltering of the service sector’s spring revival.”

On August 22, 2023, the ONS released the latest – Public sector finances, UK: July 2023 – which revealed that:

1. Total public sector spending has declined substantial over the course of the year – it was £107,849 million in January 2023 and £97,249 in July 2023.

2. Meanwhile, total current receipts have risen £88,163 million in July 2022 to £92,948 million in July 2023.

Which means that fiscal policy is not providing any income boost to the nation as the rising interest rates squeeze interest-sensitive expenditure components, such as business investment.

The point is that the policy settings in Europe and the UK are completely mismatched for the situation.

Inflation is falling not because of the interest rate increases but because the supply factors that have been driving it are abating and because some regulated prices are being adjusted downwards.

However, fiscal policy is too tight and monetary policy settings are ridiculous.

These nations might reasonably look to Japan for guidance.

They were patient about the inflation and sought to use fiscal policy to provide cash relief for the cost-of-living pressures on households while waiting for the inflationary pressures to abate.

The Bank of Japan maintained its low interest rate regime because they understood that increasing interest rates would do nothing to address the main inflationary drivers and would just hurt low-income mortgage holders.

We are now entering phase 2 of the New Keynesian policy folly.

Phase 1 – was the rising interest rates to fight an inflation that was not interest-rate sensitive.

Phase 2 – run policy so tight that recession is inevitable.

The upshot will be a resolving inflationary situation and millions in lost incomes and jobs as the legacy of this folly.

Meanwhile, you have William Keegan of the UK Guardian, who has written his one-millionth or something article demand that Britain vote to abandon Brexit and return to the European Union, as if that EU is something desirable.

His latest article (August 20, 2023) which I won’t link to continues his 800-or-so word diatribes that essentially amount to nothing more than “I wish we had voted differently”.

It is as if the golden land lies across the Channel to the east and all manner of torment lies on the west side.

The fact is that the torment on the west side is self inflicted and has little to do with the decision to leave the EU.

And on the east side – well the dysfunction continues with recession looming.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2023 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.