In my most recent podcast – Letter from The Cape Podcast – Episode 14 – I provided a brief introductino to why economic reports that project fiscal crises based on ageing population estimates miss the point and bias policy to making the actual problem worse. Today, I will provide more detail on that theme. Last week (August 24, 2023), the Government via the Treasury released its – 2023 Intergenerational Report – which purports to project “the outlook of the economy and the Australian Government’s budget to 2062-63”. It commands centre stage in the public debate and journalists use many column inches reporting on it. Unfortunately, it is a confection of lies, half-truths interspersed with irrelevancies and sometimes some interesting facts. Usually, these reports (the 2023 edition is the 6th since this farcical exercise began in the 1998) are a waste of time and effort.

Genesis

The genesis of these reports goes back to the Charter of Budget Honesty Act 1998, brought in by the previous conservative government, who ironically were one of worst lying governments in our history.

The Act embodied all the fictions that pervade discussion of fiscal policy, as you will glean from its Purpose:

The Charter of Budget Honesty provides a framework for the conduct of Government fiscal policy. The purpose of the Charter is to improve fiscal policy outcomes. The Charter provides for this by requiring fiscal strategy to be based on principles of sound fiscal management and by facilitating public scrutiny of fiscal policy and performance.

Old fashioned sound finance.

“Improve fiscal policy outcomes” is defined in terms of financial ratios, with a preference for fiscal surpluses without regard to functional outcomes.

As I have noted many times, there is no meaning that can be gained by just comparing fiscal numbers.

A 3 per cent of GDP deficit is not better or worse than a 10 per cent deficit or a 2 per cent surplus.

It all depends on the context – which is defined in terms of real outcomes such as the rate of unemployment, the desires of the non-government sector to save, the state of the external economy and more.

Only by matching the context with aspirational goals (such as full employment) can we deduce whether the current fiscal position is the right one.

Part 6 of the Act says that:

The Treasurer is to publicly release and table intergenerational reports as follows:

(a) the first intergenerational report is to be publicly released and tabled within 5 years after the commencement of this Act;

(b) subsequent intergenerational reports are to be publicly released and tabled within 5 years of the public release of the preceding report.

The first Intergenerational Report came out in 2002, which the then government published (as part of the Budget Papers) to provide a justification for their pursuit of budget surpluses.

It was the first major document to promote the ageing population-fiscal burden nexus.

The current 6th edition of this exercise has stayed on message – governments must move to surplus and reduce the tax burden on future generations.

The problem is that the message is deeply flawed when we match the aspiration to the actual policies being recommended.

More on this to come.

The 2023 Report

From page xii of the 2023 Report we read:

Fiscal sustainability is critical for delivering essential public services, providing fiscal buffers for economic downturns and maintaining macroeconomic stability.

Notwithstanding recent actions that have improved the near-term fiscal position, Australian Government debt-to-GDP remains high by historical standards, long-term spending pressures are growing, and the revenue base is narrowing as the population ages …

Recent actions to improve the budget position have assisted in rebuilding fiscal buffers after the COVID-19 pandemic and contributed to an improved long-term fiscal outlook since the 2021 IGR …

Lower debt today means a lower interest burden in the future, providing governments with more flexibility to sustain essential services, invest in emerging priorities and respond to economic shocks …

So you can see the fictions are all well-articulated.

Fiscal sustainability is defined in terms of the ‘state’ of the fiscal outcome, which, as above, would claim a surplus is better than a deficit and so on.

The claim is that surpluses represent ‘saving’ which can be stored away as a ‘fiscal buffer’ and used in a rainy day!

The problem is that this narrative makes no sense as I will explain below.

As background reading, you might like to read these early posts that discuss this topic in detail:

1. Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 1 (June 15, 2009).

2. Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 2 (June 16, 2009).

3. Fiscal sustainability 101 – Part 3 (June 17, 2009).

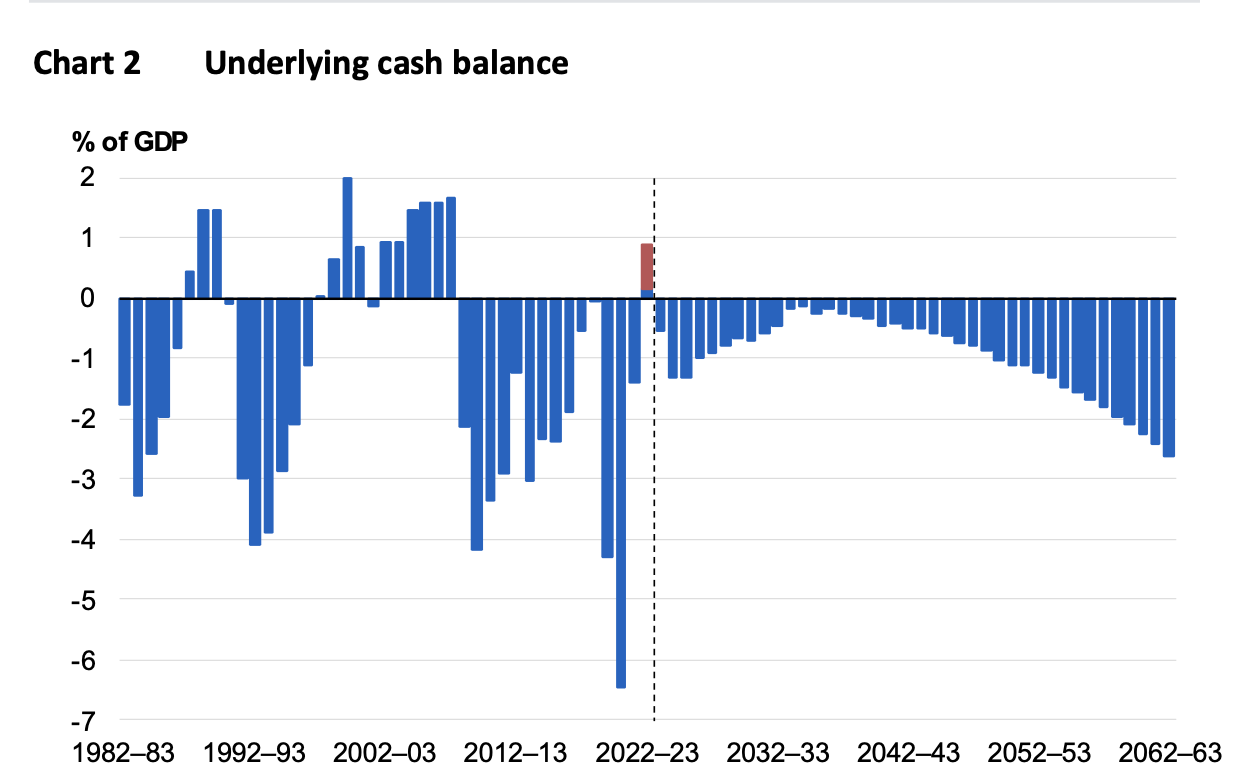

The Report provides this projection of the fiscal position of the federal government out to 2062-63 (I have just reproduced Chart 2).

The explanation provided is that:

Budget deficits narrow initially, but then widen from the 2040s due to growing spending pressures … The five fastest-growing payments are health, aged care, the NDIS, interest on government debt, and defence.

So as the population ages more public funding will be required in health and aged care.

Although less will be required to service the declining share of children.

Notice that this is graph is introduced without any mention of what the net spending would be achieving or what the non-government sector might be doing by way of debt-retrenchment and saving.

From the perspective of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) perspective, federal finances can be neither strong nor weak but in fact merely reflect a scorekeeping role.

Assuming the government’s projections are accurate (just for the sake of argument), then the way I view the graph is that over time, the non-government $A financial asset wealth will rise over the projected period.

And that fiscal policy will be supporting economic growth and income growth in the non-government sector.

The missing information which would be required to say anything sensible about the graph relates to things such as the state of the labour market, whether public infrastructure is being maintained, how much income is coming in through net exports etc.

The about 2.8 per cent of GDP deficit in 2062 might be appropriate depending on these considerations.

It is difficult to go further on this tack because the Report is very vague when it comes to crucial assumptions.

The Appendices do provide ‘Economic and fiscal projections’ but not in sufficient detail to tie it all together.

For example, the Report doesn’t articulate what the external account will look like.

There are some hints – such as the terms of trade will fall and become constant over the projection period.

We learn that the government thinks that:

… key commodity prices are assumed to decline to their long-run anchors over four-quarters to be at their long-run level by 2024–25 and remain at these levels over the projection period. The terms of trade are projected to remain around their 2024–25 level over the projections. …

The strong terms of trade is the primary reason the external balance has been in small surplus in recent years after many decades of being in deficit of around 3.5 per cent of GDP.

So can we assume that the economy will be returning to running current account deficits over this period or not?

If the economy is to return to its historical position (external deficits), then the fiscal deficits will be essential to maintain sufficient domestic demand at levels consistent with full employment.

The only other alternative is for the private domestic sector (as a whole) to move into further indebtedness.

The household sector in Australia is already carrying record levels of indebtedness and has only limited scope to expand those liabilities.

It is not a sustainable strategy to rely on ever increasing levels of private debt for economic growth when the nation is running an external deficit.

So far from worrying that the projected fiscal deficits are too large, my worry is that they might be too small given the challenges that face the nation over the next several decades and the public investment that those challenges will necessitate.

Worrying arithmetic

The government is forecasting a significant slowing of economic growth over the projection period from 3.1 per cent in 2022-23 to 1.9 per cent by 2062-63.

They also project that participation rates will rise from 80.1 per cent to 82.3 per cent.

The working age population is forecast to rise from 17.2 million in 2022-23 to 24.8 million by 2062-63.

Labour productivity growth is forecast to be around 1.1 per cent per annum throughout.

While they say nothing about the evolution of unemployment, we can bring these figures together to forecast an unemployment rate for each decade of the forecast period.

Arthur Okun created a rule of thumb that allowed us to approximate how much unemployment will change for each percentage change in real GDP growth.

The rule of thumb says that if the unemployment rate is to remain constant, the rate of real output growth must equal the rate of growth in the labour force plus the growth rate in labour productivity.

Labour force growth adds to the labour supply and the number of jobs necessary to be created to keep the unemployment rate constant, whereas labour productivity growth reduces the labour requirements for each percentage point of output growth.

So if the required real GDP growth rate (labour force plus labour productivity growth) is greater than the actual real GDP growth rate in any year, then the unemployment rate will rise by the difference in points.

I discuss the technicalities of this rule of thumb in this blog post – Okun’s Law survives 50 years – trouble for the neo-liberals (January 27, 2013).

Now bringing those forecasts together we see that:

| Aggregate | 2022-23 to 2032-33 | 2032-33 to 2042-43 | 2042-43 to 2052-53 | 2052-53 to 2062-63 |

| Labour Force growth (per annum) | 1.4 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 0.7 |

| Productivity growth (per annum) | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| Required GDP growth (per annum) | 2.7 | 2.4 | 1.9 | 1.8 |

| Projected GDP growth (per annum) | 2.5 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 1.9 |

| Change in Unemployment Rate (per annum) | 0.2 points | 0.2 points | -0.1 points | -0.1 points |

So for the next two decades, the growth in the labour force and labour productivity growth outstrips the projected GDP growth which means that the unemployment rate is steadily rising during this period.

If we were to believe the projections that means by 2042-43, the unemployment rate would have risen by 4 percentage points then fall by 2 percentage points by the end of the period (2062-63).

Which means that the unemployment is projected to rise by 2 percentage points and be around 5.7 per cent.

Then reflect on the statements in the Report about the so-called NAIRU.

The Report says:

The 2023–24 Budget projected the unemployment rate would rise modestly from its current lows to 41⁄2 per cent in 2024–25 but remain low by historical standards. The unemployment rate settles at Treasury’s assumption for the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU) by 2026–27 and remains there over the rest of the projection period.

Which is not consistent with the other projections unless they forecast significant changes in working hours, which they say nothing about.

At any rate, the aspiration of the federal government is to lock in high involuntary unemployment for the next 40 years.

A dismal ambition.

National saving and financial buffer myths

The entire logic underpinning the intergenerational debate is flawed.

Financial commentators often suggest that fiscal surpluses in some way are equivalent to accumulation funds that a private citizen might enjoy.

Recall the reference above to building up buffers and ‘national saving’.

This idea that accumulated surpluses allegedly ‘stored away’ will help government deal with increased public expenditure demands that may accompany the ageing population lies at the heart of the intergenerational debate misconception.

While it is moot that an ageing population will place disproportionate pressures on government expenditure in the future, it is clear that the concept of pressure is inapplicable because it assumes a financial constraint.

A sovereign government in a fiat monetary system is not financially constrained.

There will never be a squeeze on ‘taxpayers’ funds’ because the taxpayers do not fund ‘anything’.

The concept of the taxpayer funding government spending is misleading.

Taxes are paid by debiting accounts of the member commercial banks accounts whereas spending occurs by crediting the same.

The notion that ‘debited funds’ have some further use is not applicable.

When taxes are levied the revenue does not go anywhere.

The flow of funds is accounted for, but accounting for a surplus that is merely a discretionary net contraction of private liquidity by government does not change the capacity of government to inject future liquidity at any time it chooses.

The standard government ‘intertemporal budget constraint’ analysis that deficits lead to future tax burdens is erroenous.

The idea that unless policies are adjusted now (that is, governments start running surpluses), the current generation of taxpayers will impose a higher tax burden on the next generation is deeply flawed.

The government budget constraint is not a “bridge” that spans the generations in some restrictive manner.

Each generation is free to select the tax burden it endures.

Taxing and spending transfers real resources from the private to the public domain.

Each generation is free to select how much they want to transfer via political decisions mediated through political processes.

When modern monetary theorists argue that there is no financial constraint on federal government spending they are not, as if often erroneously claimed, saying that government should therefore not be concerned with the size of its deficit.

MMT does not advocate unlimited deficits.

Rather, the size of the deficit (surplus) will be market determined by the desired net saving of the non-government sector.

This may not coincide with full employment and so it is the responsibility of the government to ensure that its taxation/spending are at the right level to ensure that this equality occurs at full employment.

Accordingly, if the goals of the economy are full employment with price level stability then the task is to make sure that government spending is exactly at the level that is neither inflationary or deflationary.

This insight puts the idea of sustainability of government finances into a different light.

The emphasis on forward planning that has been at the heart of the ageing population debate is sound.

We do need to meet the real challenges that will be posed by these demographic shifts.

But if governments continue to try to run fiscal surpluses to keep public debt low then that strategy will ensure that further deterioration in non-government savings will occur until aggregate demand decreases sufficiently to slow the economy down and raise the output gap.

So does the dependency ratio matter?

It surely does but not in the way that is usually assumed.

The standard dependency ratio is normally defined as 100*(population 0-15 years) + (population over 65 years) all divided by the (population between 15-64 years). Historically, people retired after 64 years and so this was considered reasonable. The working age population (15-64 year olds) then were seen to be supporting the young and the old.

The aged dependency ratio is calculated as:

100*Number of persons over 65 years of age divided by the number of persons of working age (15-65 years).

The child dependency ratio is calculated as:

100*Number of persons under 15 years of age divided by the number of persons of working age (15-65 years).

The total dependency ratio is the sum of the two. You can clearly manipulate the “retirement age” and add workers older than 65 into the denominator and subtract them from the numerator.

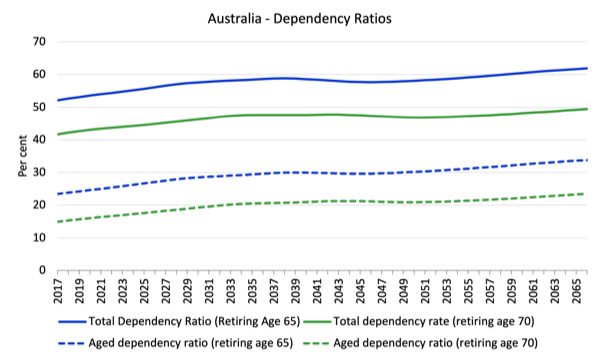

The following graph uses the ABS Series B demographic projections and computes dependency ratios based on a retirement age of 65 and then if the retirement age rises to 70.

The three projected ratios for a retirement age of 65 at 2062-63 would be 61.9 per cent (total); 28.1 per cent (child) and 33.8 (aged).

However, if you raised the retirement age to 70, the numbers drop to 49.6 per cent (total); 25.9 per cent (child) and 23.5 per cent (aged).

s an aside, there is no legal retirement age in Australia but it typically means when you can qualify for a state pension and it also has a meaning in terms of superannuation rules (entitlements don’t compound after that, typically).

So you can see why the push is on to increase the retirement age.

While there is a lot of hysteria about the dependency ratio what it means is that in 2023 there are 1.82 people of working age to every person who is not of working age.

Under the ABS demographic projections this will fall to 1.61 in 2062-63.

However, if we want to actually understand the changes in active workers relative to inactive persons (measured by not producing national income) over time then the raw computations are inadequate.

Then you have to consider the so-called effective dependency ratio which is the ratio of economically active workers to inactive persons, where activity is defined in relation to paid work. So like all measures that count people in terms of so-called gainful employment they ignore major productive activity like housework and child-rearing. The latter omission understates the female contribution to economic growth.

Given those biases, the effective dependency ratio recognises that not everyone of working age (15-64 or whatever) are actually producing.

There are many people in this age group who are also “dependent”.

For example, full-time students, house parents, sick or disabled, the hidden unemployed, and early retirees fit this description.

I would also include the unemployed and the underemployed in this category although the statistician counts them as being economically active.

If we then consider the way the neo-liberal era has allowed mass unemployment to persist and rising underemployment to occur you get a different picture of the dependency ratios.

They will be much higher than the Report projects and bears on the next point.

The reason that mainstream economists believe the dependency ratio is important is typically based on false notions that the government is financially constrained.

So a rising dependency ratio suggests that there will be a reduced tax base and hence an increasing fiscal crisis given that public spending is alleged to rise as the ratio rises as well.

So if the ratio of economically inactive rises compared to economically active, then the economically active will have to pay much higher taxes to support the increased spending. So an increasing dependency ratio is meant to blow the deficit out and lead to escalating debt.

These myths have also encouraged the rise of the financial planning industry and private superannuation funds which blew up during the recent crisis losing millions for older workers and retirees. The less funding that is channelled into the hands of the investment banks the better is a good general rule.

But all of these claims are not in erroneous and should not guide policy planning.

The promotion of these fiscal fictions then leads to all sorts of policy errors.

1. Apparently we have to make people work longer despite this being very biased against the lower-skilled workers who physically are unable to work hard into later life.

2. We are also encouraged to increase our immigration levels to lower the age composition of the population and expand the tax base.

3. Further, we are told relentlessly that the government will be unable to afford to provide the quality and quantity of the services that we have become used too.

However, all of these remedies miss the point overall.

It is not a financial crisis that beckons but a real one.

Are we really saying that there will not be enough real resources available to provide aged-care at an increasing level?

That is never the statement made.

The worry is always that public outlays will rise because more real resources will be required “in the public sector” than previously.

But as long as these real resources are available there will be no problem.

In this context, the type of policy strategy that is being driven by these myths will probably undermine the future productivity and provision of real goods and services in the future.

For example, it is clear that the goal should be to maintain efficient and effective medical care systems.

Clearly the real health care system matters by which I mean the resources that are employed to deliver the health care services and the research that is done by universities and elsewhere to improve our future health prospects. So real facilities and real know how define the essence of an effective health care system.

Further, productivity growth comes from research and development and in Australia the private sector has an abysmal track record in this area. Typically they are parasites on the public research system which is concentrated in the universities and public research centres (for example, CSIRO).

For all practical purposes there is no real investment that can be made today that will remain useful 50 years from now apart from education.

Unfortunately, tackling the problems of the distant future in terms of current “monetary” considerations which have led to the conclusion that fiscal austerity is needed today to prepare us for the future will actually undermine our future.

The irony is that the pursuit of fiscal austerity leads governments to target public education almost universally as one of the first expenditures that are reduced.

Most importantly, maximising employment and output in each period is a necessary condition for long-term growth.

The emphasis in the mainstream integenerational debates that we have to lift labour force participation by older workers is sound but contrary to current government policies which reduces job opportunities for older male workers by refusing to deal with the rising unemployment.

Anything that has a positive impact on the dependency ratio is desirable and the best thing for that is ensuring that there is a job available for all those who desire to work.

Further encouraging increased casualisation and allowing underemployment to rise is not a sensible strategy for the future.

The incentive to invest in one’s human capital is reduced if people expect to have part-time work opportunities increasingly made available to them.

But all these issues are really about political choices rather than government finances.

The ability of government to provide necessary goods and services to the non-government sector, in particular, those goods that the private sector may under-provide is independent of government finance.

Any attempt to link the two via fiscal policy “discipline:, will not increase per capita GDP growth in the longer term.

The reality is that fiscal drag that accompanies such “discipline” reduces growth in aggregate demand and private disposable incomes, which can be measured by the foregone output that results.

Conclusion

The idea that it is necessary for a sovereign government to stockpile financial resources to ensure it can provide services required for an ageing population in the years to come has no application.

It is not only invalid to construct the problem as one being the subject of a financial constraint but even if such a stockpile was successfully stored away in a vault somewhere there would be still no guarantee that there would be available real resources in the future.

Discussions about “war chests” completely misunderstand the options available to a sovereign government in a fiat currency economy.

Second, the best thing to do now is to maximise incomes in the economy by ensuring there is full employment.

This requires a vastly different approach to fiscal and monetary policy than is currently being practised.

Third, if there are sufficient real resources available in the future then their distribution between competing needs will become a political decision which economists have little to add.

Long-run economic growth that is also environmentally sustainable will be the single most important determinant of sustaining real goods and services for the population in the future.

Principal determinants of long-term growth include the quality and quantity of capital (which increases productivity and allows for higher incomes to be paid) that workers operate with.

Strong investment underpins capital formation and depends on the amount of real GDP that is privately saved and ploughed back into infrastructure and capital equipment.

Public investment is very significant in establishing complementary infrastructure upon which private investment can deliver returns.

A policy environment that stimulates high levels of real capital formation in both the public and private sectors will engender strong economic growth.

If we adequately fund our public universities to conduct more research which will reduce the real resource costs of health care in the future (via discovery) and further improve labour productivity then the real burden on the economy will not be anything like the scenarios being outlined in the “doomsday” reports.

But then these reports are really just smokescreens to justify the neo-liberal pursuit of fiscal austerity.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2023 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.