Last week (September 13, 2023) in Brussels, the President of the European Union delivered her annual – 2023 State of the Union Address. We all know that these events are spin-oriented and the leader of the 27-nation bloc is hardly going to come out and talk the arrangement down. But this was an election speech – with the next major elections coming in the year ahead. The President lauded all the half-baked and under-funded programs that they have initiated under her ‘leadership’ and when it came to assessing the state of the labour market she made the extraordinary statement that as a result of Commission policies (such as – SURE) “Europe is close to full employment.” Yes, they are spinning the view that the problem is not a lack of jobs but “millions of jobs are looking for people” while admitting that “8 million young people are neither in employment, education or training” – the so-called NEET generation. Language should above all else convey meaning. Trying to claim that Europe is close to full employment violates that basic aspiration. The reality is that Europe is nowhere close.

Official unemployment rates – still persistently high

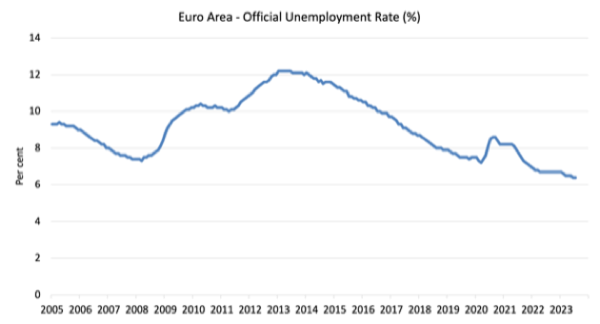

The first graph shows the official unemployment rate for the 20 Member States of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) or Eurozone.

The current rate is 6.4 per cent and it has been around that rate for several months now.

It is true that this is the lowest rate experienced since the inception of the common currency.

But is an official rate of 6.4 per cent really close to full employment?

It means that as at July 2023 (latest data available from Eurostat) there were still 10,944 thousand workers who were available and willing to work without work.

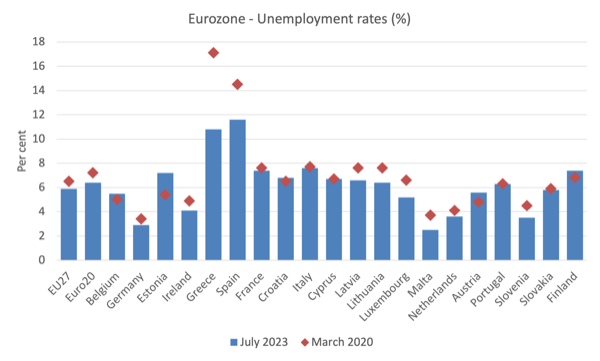

There is also considerable disparity in unemployment rates across the 20 Member State bloc.

The next graph compares the unemployment rates as at March 2020 (at the onset of the pandemic) with the situation as at July 2023.

There have been minimal reductions in the rates between that time across the nations involved.

Clearly, Greece and Spain have seen significant reductions in their unemployment rates, but from a very high base and both nations are still enduring mass unemployment – Greece 10.8 per cent, Spain 11.6 per cent.

Moreover, the unemployment rose in July (relative to June) in 9 of the 20 Member States and only declined over the period in 4 states.

In some cases, the unemployment rate has worsened (Belgium, Estonia, Croatia, Austria and Finland).

And think about the official rates in say, Norway (3.5 per cent), US (3.5 per cent), and Japan (2.7 per cent).

Even the UK, the recently departed former EU member had an unemployment rate of 4.3 per cent in July 2023, elevated in terms of recent years but still well below the Eurozone or the EU27 aggregate.

Why is the European Commission claiming that an unemployment rate of 6.4 per cent is as low as the bloc can achieve?

So even just focusing on the official unemployment rate it is hard to justify a claim that more people cannot be provided with employment than currently.

Skill Shortages

The President asserted that the real problem was not the lack of jobs but a lack of workers:

Instead of millions of people looking for jobs, millions of jobs are looking for people.

The most recent European Commission (Eurobarometer) survey (published September 2023 but conducted May 2023) – European Year of Skills – Skills shortages, recruitment and retention strategies in small and medium-sized enterprises – provides some interesting results (in as much as they can be believed).

Overall, 52 per cent of EU27 SMEs surveyed said that they found it “very difficult” to “Find workers with the right skills”.

Yet, 52 per cent of the same SMEs said it was either “Very difficult” or “Moderately difficult” to “Retain skilled workers”.

Which raises the question as to why these firms struggle to retain their existing workforce.

Perhaps the reason they find it hard to attract new workers is because they are not offering conditions conducive and their existing workforces know this and turnover regularly.

Moreover, 55 per cent of these firms admitted it was difficult (Very, Moderately, or Slightly) to “Assess the training needs of the staff” – which raises the question of the quality of their skill development processes and their ability to assess skill requirements anyway.

Which – impacts on the veracity of their answers to whether it is skill shortages restricting their activities or management incompetence.

Similarly, 58 per cent said it was difficult to “Identify appropriate training opportunities for the staff”.

Why such a high proportion?

And, 55 per cent said it was difficult to “Finance staff training” – which probably means they have chased expansion at the expense of appropriate forward planning.

And, 70 per cent said it was difficult for staff to “Find time for your staff to participate in training” – again insufficient forward planning.

When I analyse these surveys, I always am interested in assessing the strategies that firms implement to address so-called ‘skill shortages’.

Often we find that the existence of a ‘skill shortage’ is really just a sign that the firm is unwilling to offer attractive wages.

A true skill shortage should see wages rising rapidly as firms compete for available skilled staff.

That is not evident in aggregate European Commission data and the SME survey noted above shows that only 32 per cent of firms who claim skill shortages are holding them back say they are willing to “Increase job attractiveness in terms of financial and/or non-financial benefits” in order to attract more skilled staff to their workplaces.

The point is that if they are truly being ‘held back’ then they would have potential sales that they cannot meet.

Which means that if they are unwilling to pay higher wages to expand their level of activity, then the profitability of expansion must be questionable.

Or, they are unwilling to give workers a higher share of the potential extra revenue.

Neither option tells me that these skill shortages are technically binding.

Interestingly, 70 per cent said that they were getting ‘Not very much’ or ‘No effort at all’ from “EU level organisations/authorities” in terms of support to solve the skills issue.

So if these ‘skills shortages’ were really holding the European Union back, we would expect greater fiscal support being offered.

So the President’s words in this regard appear hollow.

And 65 per cent of firms said they were “Not at all familiar” with “EU policy initiatives for skills (such as Pact for Skills, European Alliance for Apprenticeships or the Centres of Vocational Excellence)”.

And 54 per cent said they were “Not at all familiar” with “EU funding programmes for skills (such as European Social Fund Plus or Erasmus+)”.

And 70 per cent said they were “Not at all familiar” with “EU initiatives facilitating hiring skilled workers from abroad (such as Blue Card)”.

So there is a communication problem between the sprawling Brussels bureaucracy and the economic units that provide work in the Union.

Broader indicators of labour slack

As I explained many times, the official unemployment rate is a very narrow measure of labour slack and in assessing whether a nation is currently at or close to full employment, we have to consider broader measures that take into account:

1. underemployment.

2. hidden unemployment.

3. marginal attachments.

On September 13, 2023, Eurostat updated their – EU labour market – quarterly statistics – which include some broader measures of labour slack in the European Union.

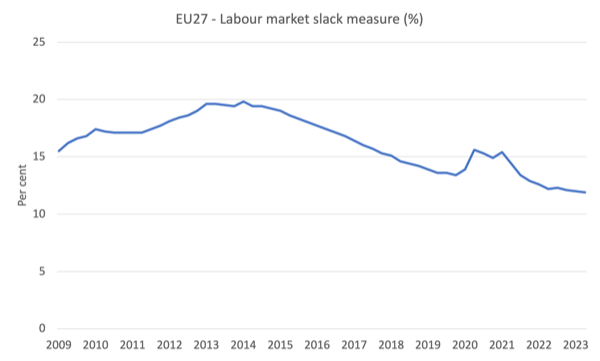

This graph was drawn from the dataset – Labour market slack by sex and age – quarterly data – and shows Eurostat’s broad measure of labour market slack.

Labour market slack measures the “unmet need for work” and there were 23.9 million persons across the European Union in that state.

It is:

… the sum of unemployed persons, underemployed part-time workers, persons seeking work but not immediately available and persons available to work but not seeking, expressed as percentage of the extended labour force.

In the June-quarter 2023, the labour market slack was estimated to be 11.9 per cent and has been around that mark since June last year.

The components that comprise the measure are:

1. Official unemployment – 11.9 million in the June-quarter 2023.

2. Underemployment part-time workers (those in employment but who want and cannot find more hours) – 5,595 thousand or 2.4 per cent.

3. Those available for work but not seeking work – 6,215 thousand or 2.5 per cent.

4. Those actively seeking work but not available to take up work – 2,030 thousand or 0.8 per cent.

Eurostat doesn’t publish readily available data on the extra hours of work that underemployed part-time workers desire.

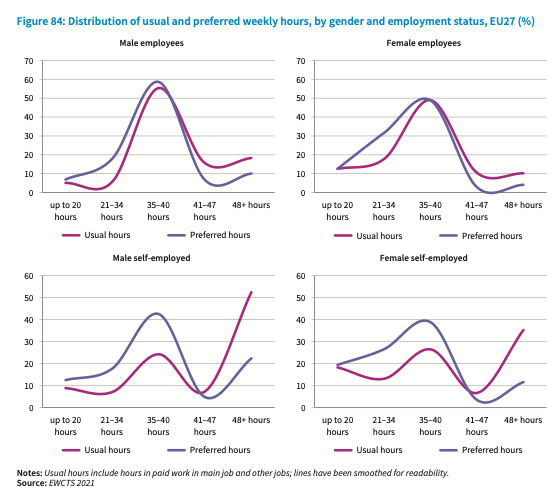

But the European Working Conditions Survey publication – Working conditions in the time of COVID-19: Implications for the future (published November 29, 2022) – does provide some information that is helpful.

The last survey was 2021 (every five years) and Figure 84 (reproduced below) gives us some idea of the extra hours preferred.

The EWCS notes that:

A preference for longer working hours, which may to some extent reflect underemployment, was more common among younger workers (24% of those aged 16–24 years), temporary employees with contracts of less than a year (24%), workers in elementary occupations (26%), and services and sales workers (19%), and in the commerce and hospitality (16%) and transport (15%) sectors

Overall, it begs meaning to think that when 11.9 per cent of available labour are without work in one way or another that the system is ‘close to full employment’.

OECD data for – Temporary Employment – indicates that 14.1 per cent of wage and salary employment is temporary (that is, has a “pre-determing termination date”).

Conclusion

While politicians continually want to claim that their nations or areas of responsibility are ‘close to full employment’ the data rarely bears out that assessment.

And think of it this way – the mainstream economists like to tell us that full employment occurs when inflation is stable.

In June 2022, the EU27 inflation rate was 9.6 per cent.

In June 2023, it had steadily fallen to 6.4 per cent.

What that means – if we apply the mainstream logic is that the unemployment rate between those dates was above their measure of full employment.

Inflation is expected to continue to decline in the coming months.

So the mainstream concept of a ‘full employment’ unemployment rate must be below the current official unemployment rate.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2023 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.