Today (September 25, 2023), the Australian government issued its – Working Future: The Australian Government’s White Paper on Jobs and Opportunities – statement, which portends to define labour market vision and policy for the years to come. White Paper’s are grand statement and this one falls short of that requirement. Compared to the path-breaking – The 1945 White Paper on Full Employment – which set the path for several decades of prosperity for workers, the current effort by the government is a mediocre affair. It is just a restatement of the NAIRU cult that has justified the so-called ‘activation’ or supply-side approach to labour market policy, which effectively relegates macroeconomic policy to the bench and considers micro policies are required to reduce the NAIRU and the measured unemployment rate. This is the failed strategy that has dominated for the last three decades and has cause the problems that the White Paper claims it wants to address. Its release today demonstrates that the Labor Government is really just a neoliberal-lite outfit – full of spin but short on any directional shift in policy. It is very dispiriting.

If you scan the – Appendix A – Glossary of Terms – you will not find a definition of full employment.

The Non-Accelerating-Inflation-Rate-of-Unemployment (NAIRU) is defined, as is ‘Employability skills’ but there is no formal statement of what constitutes full employment.

And that appears odd, given that Chapter 2 is entitled ‘Delivering sustained and inclusive full employment’.

Howwever, once we start reading that Chapter it soon becomes clear that the emphasis remains on the supply-side – workers’ skills, training, employability – rather than stating a firm commitment by government to ensure there are enough jobs available to meet the desires of workers for hours of work.

The Report sets the tone with:

Macroeconomic policy has done a good job of managing swings in employment over the business cycle, but significant underutilisation persists reflecting structural changes and challenges.

The problem is that macroeconomic policy has not ‘done a good job’ of ensuring there are sufficient jobs even as the structure of the economy evolves.

It is a cop out – common among mainstream economists who want to disabuse us of the effectiveness of macroeconomic policy – to conclude that the problems are ‘structural’ – which then leads to discussions about workers not being skilled enough or living in the wrong areas.

And that leads into discussions about training and motivation incentives and all the rest of the ‘activation’ programs that have defined the neoliberal era.

And that activation approach is exactly why there remains ‘significant underutilisation’ of labour.

The overwhelming characteristic of the neoliberal era with respect to the labour market is that our economies do not produce enough jobs and hours of work to meet the desires of the workforce.

That is a demand shortfall.

And the reason for that shortfall is that governments have eschewed the use of macroeconomic policy to ensure that demand gaps are zero.

And the reason for that is that they have fallen prey to the ‘NAIRU cult’, which dominates my profession in the academy and in senior policy-making circles and prioritises using labour underutilisation as a policy tool rather than a policy target in a misguided pursuit of low inflation.

The mainstream economists talk about cost-benefit and marginal calculus but never offer a thorough analysis of the relative costs of maintaining mass unemployment to get the benefits of low inflation.

Simply put, the daily income losses from mass unemployment for the economy as a whole are larger than any microeconomic inefficiency we can think of and the greatest gain an economy can make is to ensure all those who want to work can up to their desired hours.

We do get a working definition in the White Paper as to what the Government thinks constitutes full employment:

Everyone who wants a job should be able to find one without searching for too long.

That also add a qualitative dimension to the job sufficiency requirement:

We want people to be in decent jobs that are secure and fairly paid. This is a broader and longer-term objective than achieving the current maximum sustainable level of employment consistent with low and stable inflation.

The rub is in the ‘longer term’ qualification.

The inference is that the ‘maximum sustainable level of employment’ is the NAIRU and policy might work to bring the ‘broader’ concept into line with the NAIRU over some ‘longer’ time horizon.

Which is exactly what the supply-side agenda has been all about for decades.

The agenda denies that macroeconomic policy can reduce the unemployment below the ‘estimated NAIRU’ without causing accelerating inflation and that over time supply-side (microeconomic) policies, such as maintaing below poverty rate income support systems to engender incentives to work (read: elevate the sense of desperateness among the jobless) and maintaining punitive surveillance systems as part of a mutual obligation among the income support recipients (read: punish the most disadvantaged because the government will not use its undoubted capacity to create enough jobs), have to grind the workers into submission.

The White Paper emphasises:

Achieving this objective requires a labour market in which people can find work quickly enough that their work skills remain current and the financial and other harms of unemployment are limited.

Which should have read – ‘requires that there are sufficient jobs’ rather than pushing the onus back on the ‘search’ effectiveness.

I published an academic paper a long time ago which I summarised in a blog post – The unemployed cannot find jobs that are not there! (April 14, 2009) – which addressed this issue.

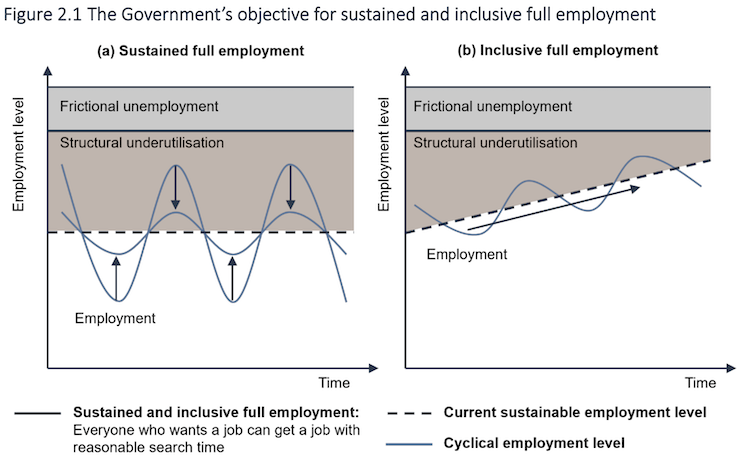

The NAIRU Cult soon becomes explicit in the two-part strategy that is articulated:

Sustained full employment: is about using macroeconomic policy to reduce volatility in economic cycles and keep employment as close as possible to the current maximum sustainable level of employment that is consistent with low and stable inflation …

Inclusive full employment: is about broadening labour market opportunities, lowering barriers to work, and reducing structural underutilisation to increase the level of employment that can be sustained in our economy over time …

There it is – this could have been written in the 1980s when the NAIRU monster became mainstream.

Macroeconomic policy is thus confined to being about inflation stability, while micro, supply-side policy is about pushing and shoving workers to fit the measly jobs that are created in the private market.

It is a failed agenda and has led to the rise of the gig economy.

It has been responsible for the elevation and persistence of underemployment.

It has justified and maintain the below poverty line, income support systems.

It has promoted the pernicious coercion of the unemployed to participate in meaningless and ineffective training programs.

It has fostered the enrichment of the privatised ‘unemployment industry’ – the job service providers who have only succeeded in achieving one thing – extracting billions of public money to the benefit of the corporate owners and managers while using the unemployed as meagre pawns in this enrichment process.

It was meant to solve ‘skill shortage’ problems yet after billions have been funnelled into the private job service providers who were meant to be retraining workers, employers still complain endlessly about skill shortages.

And use that alleged state to further attack wages and conditions of work.

The White Paper presents their vision graphically with this lame diagram:

Which means the Government considers it appropriate to use macroeconomic policy to deliberately push people into unemployment if the unemployment rate is below the dotted horizontal line – in what they call the ‘structural underutilisation’ zone.

I did a PhD and my early work was focused on demonstrating that this ‘zone’ was, in fact, sensitive to macroeconomic policy and what looked liked a structural imbalance was in fact capable of being reduced when macroeconomic policy drove the unemployment rate down.

Search my blog for ‘hysteresis’ if you want to learn more about that concept and my work on it.

But think about the scale depicted in this graph (taking the left-panel for discussion).

Frictional unemployment is typically considered to be around 2 per cent, but could be lower these days with the power of the Internet and computers improving the flow of information between workers and employers.

If it is say 2 per cent, and we use the NAIRU estimates from Treasury or the RBA which are around 4.5 per cent, then the graph is suggesting that structural unemployment is around 3 per cent.

Obviously, that would be ridiculous given the current unemployment rate is 3.7 per cent and inflation is falling.

The Treasury should have noted the graph was not to scale.

Groupthink-speak

The White Paper also claims that:

History has shown that significantly misjudging the current maximum sustainable level of employment, or failing to take adequate account of short-term constraints, can lead to serious policy mistakes that cause higher underutilisation rates in the economy. Australia’s strong economic institutions and policy frameworks have evolved significantly over time and are well-placed to manage these risks.

This is sort of Groupthink-speak.

We don’t need very long memories – like about 1 day – to know how one of the main macroeconomic policy institutions – the Reserve Bank of Australia – is ‘significantly misjudging the current maximum level of employment’ (that is, the NAIRU).

I wrote about that in this blog post among others – Mainstream logic should conclude the Australian unemployment rate is above the NAIRU not below it as the RBA claims (July 24, 2023).

The RBA has based its massive interest rate hike policy on its claim that the NAIRU in Australia is around 4.5 per cent.

The unemployment rate has been stable for some period around 3.5 to 3.7 per cent while inflation starting falling quickly a year ago.

If you believe in the NAIRU logic, then if the unemployment rate is below the NAIRU, inflation will accelerate and vice versa.

So if the RBA was correct, then inflation should still be accelerating.

Within the NAIRU logic, the only conclusion one can make is that the unemployment rate is currently above the NAIRU because inflation continues to decline.

Significant policy mistakes are still being made – the interest rate hikes that have redistributed national income from poor (mortgage holders) to rich (asset holders) and the pursuit of fiscal surpluses – all because of significiant mistakes in understanding what the maximum employment level in Australia is.

In a section that explicitly discusses the NAIRU, the White Paper says:

… the NAIRU has several shortcomings as a measure of full employment. It evolves over time, is difficult to measure and does not capture the full potential of the workforce.

It then goes on to claim that:

… that uncertainty about the NAIRU estimates may have played a part in the RBA undershooting the inflation target between 2016 and 2019. The Review suggested that, as a result, economic growth potential went unrealised, and individual workers missed out on the benefits that work brings.

But of course, no recognition that the RBA is making a mistake in the other direction now with its interest rate hikes.

History revision

The White Paper claims that:

… the Australian economy has rarely achieved full employment for extended periods …

After the 1945 White Paper articulated the Government’s intention to use macroeconomic policy to ensure there were jobs for all, the nation maintained very low unemployment (< 2 per cent) for 3 decades or so.

Three decades is not a rare occurrence, particularly once we understand that that success was associated with correct use of fiscal policy – allowing fiscal deficits for most years to eliminate spending gaps left by non-government saving and external deficits – which ensured that spending was commensurate with maintaining full employment.

Conclusion

I will have more to say about this White Paper as I work my way through it.

On the one hand, I am tempted to just ‘throw it in the bin’ and ignore it, given it is really just a restatement of the orthodoxy that has dominated for the last 30 years – sadly for all my career.

But, one the other hand, as an academic, I have to ensure I read everything – especially grand statements from the federal government such as this one.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2023 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.