Who now remembers Long-Term Capital Management, the failure of genius, the price of hubris, and the lesson that the innocents bear the cost of their elders’ folly?

Too few, judging from investor behavior.

The collapse of LTCM was the first of three global financial crises over the past 25 years that erupted primarily in the developed world, but whose consequences were primarily borne by emerging markets economies and investors.

The world’s smaller and less liquid stock markets eternally seem forever to present tomorrow’s best investment opportunities. As Little Orphan Annie sings, “I love you, tomorrow, You’re always a day away.” As they have matured, financial transparency has improved, shareholder rights are increasingly respected, and corporate decisions are drifting in the direction of rational capital allocation rather than relational (“who you know”) allocation.

It’s much the same passion (or delusion) that drives investors in microcap stocks everywhere.

We will share a quick recap of the Three Great Storms, then highlight the fate of the EM funds that survived all three. There’s actually some good news about picking a fund that might survive the storms ahead.

The Three Great Storms

For most of the 20th century, the world’s smallest and least liquid stock markets were plagued by repeated crises. Some of those crises were of their own doing, as unreliable government structures and self-serving corporate ones conspired to undermine trust. Many, however, were not their doing. Markets with very low liquidity -relatively few buyers or sellers, relatively low trading volume, relatively low market capitalization – are hostage to the behaviors of a few, large investors. If one large investor in one small market attempts to withdraw suddenly, a market panic follows. If several large investors depart, an entire region is at risk.

So “market runs” were routine. Three events, however, stand in stark contrast to “normal” panics.

1998: Long Term Capital Management collapse 25 years ago

Long-Term Capital Management was a massive hedge fund with a stellar record and “A” tier investors, including Nobel Prize-winning economists Myron Scholes and Robert Merton, major banks, and sovereign wealth funds.

Long-Term Capital Management was a massive hedge fund with a stellar record and “A” tier investors, including Nobel Prize-winning economists Myron Scholes and Robert Merton, major banks, and sovereign wealth funds.

LTCM had placed leveraged bets on the Russian currency, but also thought they had adequately hedged those bets. They were wrong. In the spring and summer of 1998, the government of Boris Yeltsin was in turmoil. President Yeltsin fired his entire cabinet in March and appointed “take charge” guys to key posts. Short-term government interest rates popped to 150%. On August 17, Russia declared it was devaluing its currency. For good measure, it also defaulted on its bonds.

The Dow dropped 13% in two weeks as investors fled stocks, interest rates fell in response, and LTCM’s highly leveraged investments crumbled. The fund lost 50% in two weeks, threatening to bankrupt the banks, wealth, and pension funds that had invested so heavily in it. Bear Stearns demanded $500 million from the fund.

Bad things followed:

- Emerging markets got crushed. “[T]he MSCI Emerging Markets index shed 56%, as investors pulled billions of dollars out of developing economies. As of early December, investors removed all but $500 million of the $40.8 billion they committed in 2007 to the emerging markets funds tracked weekly by EPFR Global.” (Polya Lesova, “Emerging markets: the best and the worst of 2008,” MarketWatch, 12/18/2008)

- The government stepped in to save LTCM’s investors. Buffett offered LTCM pennies on the dollar for their assets. The Fed stepped in to broker a better deal in part to save the institutions put at risk by their own stupidity. The institutions involved remembered.

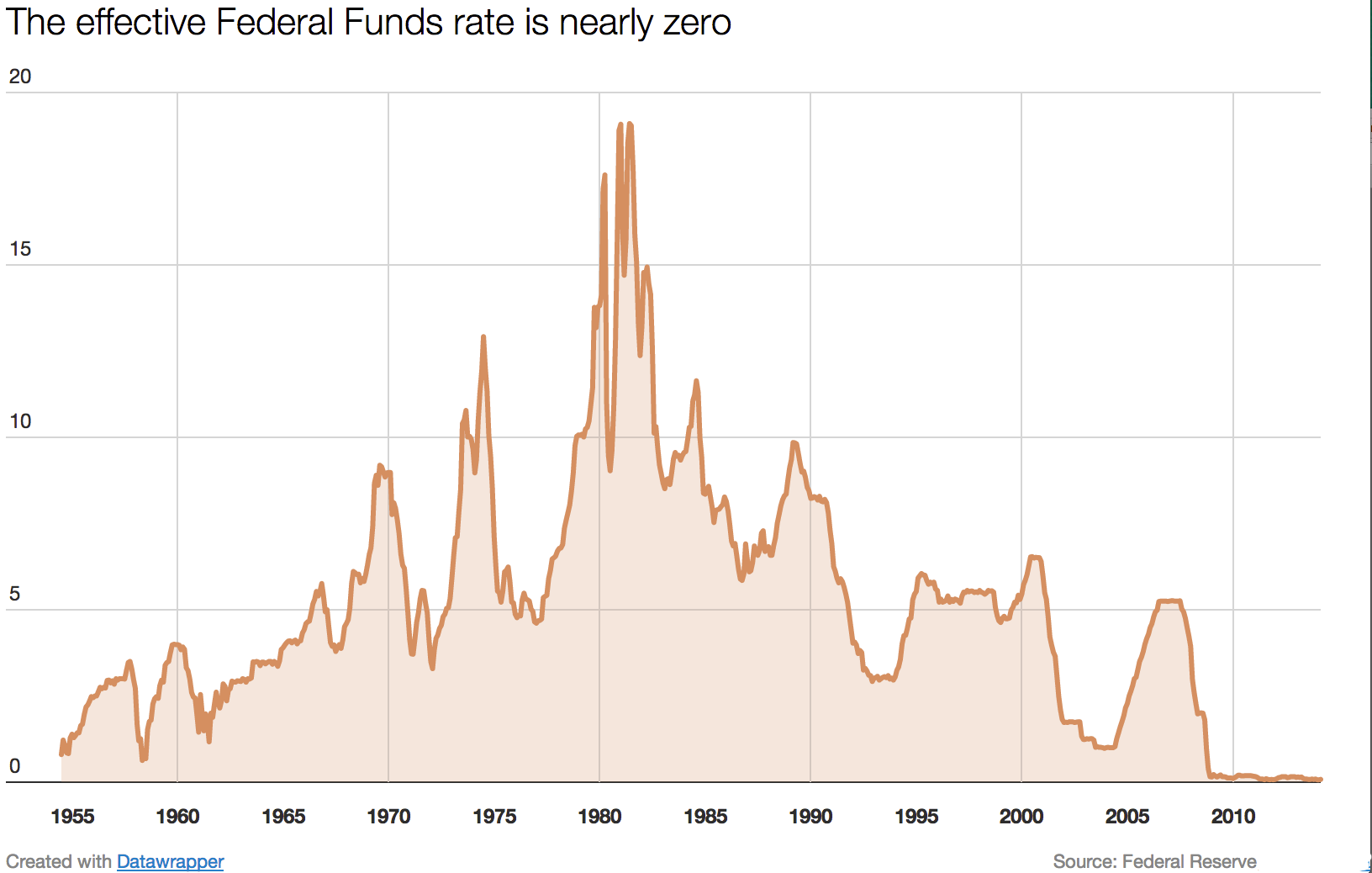

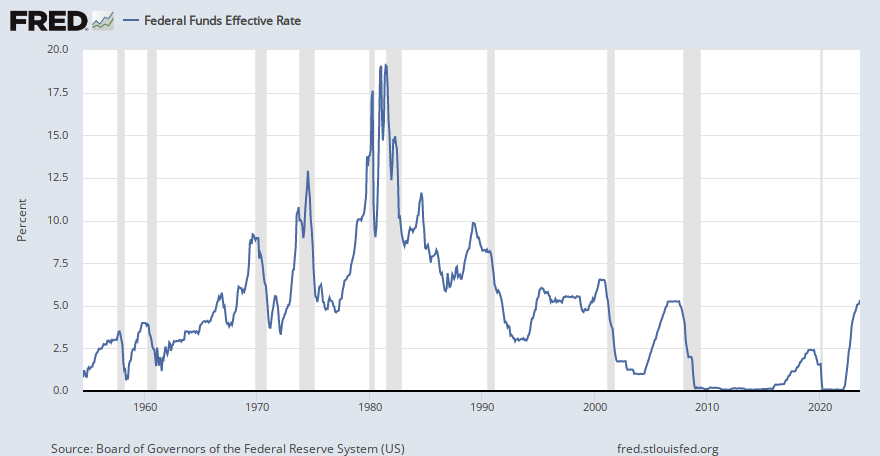

2008: The Global Financial Crisis 15 years ago

The 2008 crisis was years in the making. The shortest version is that the Fed responded to the collapse of the stock market bubble in 2000 and the attacks of 9/11/2001 by pushing interest rates down from 6.5% (in 2000) to 1% (in 2003). “Free money” routinely leads to bad decisions. People snapped up homes, prices soared, and financial institutions decided that mortgages – even mortgages held by people with no credit history and no reliable income – were great investments. They just needed to “securitize” baskets of iffy loans in a way that … somehow, canceled out all of their risks.

Until they didn’t. In 2007, companies making subprime loans started filing for bankruptcy. By mid-year, hedge funds that had invested in the loans collapsed. That summer, the global lending system froze up, and, in September, Lehman Brothers became the largest bankruptcy in American history. Investors suddenly discovered they were holding trillions in near-worthless subprime mortgages.

The worst crisis in 80 years quickly erupted. Bad things followed:

- Emerging markets got crushed. During the crisis (Nov 2007 – Feb 2009), the average EM fund lost 52% per year with a max drawdown of 62%. Emerging Europe and Russia were booking losses of 65% per year. In the following 15 years, the group returned 2.3% with a standard deviation of 22.3%.

- The government stepped in to save the global financial system. And also the morons behind the mess. The Feds cut interest rates to zero, opened emergency lending facilities, and bought securities on the open market to provide liquidity and foster calm. By the Feds’ own calculation, “Federal Reserve purchased $300 billion of Treasury securities, about $175 billion of agency debt obligations, and $1.25 trillion of agency mortgage-backed securities.” The institutions involved remembered.

2020: The Global Pandemic, three years ago

You know this story.

And its takeaway:

- Emerging markets got crushed. Since the start of COVID, the average EM has lost 1.3% annually. The median fund is down by -0.7% and has gifted investors with a 39% drawdown. Which is “less crushed” than usual, but annualized losses even after a ferocious rebound – frontier EM funds are up 13.6% YTD, EM funds up 6.2% YTD through September 2023 – is not good news.

- The government stepped in to save the financial system. Putting aside all of the heroic work to actually control the pandemic, the Feds yet again slashed rates to zero, and the other branches added trillions in stimulus (some of which was even a good idea). Both actions are complicit in the subsequent spike in inflation and the subsequent-subsequent interest rate spike.

Charting the survivors: EM Fund performance through three crises

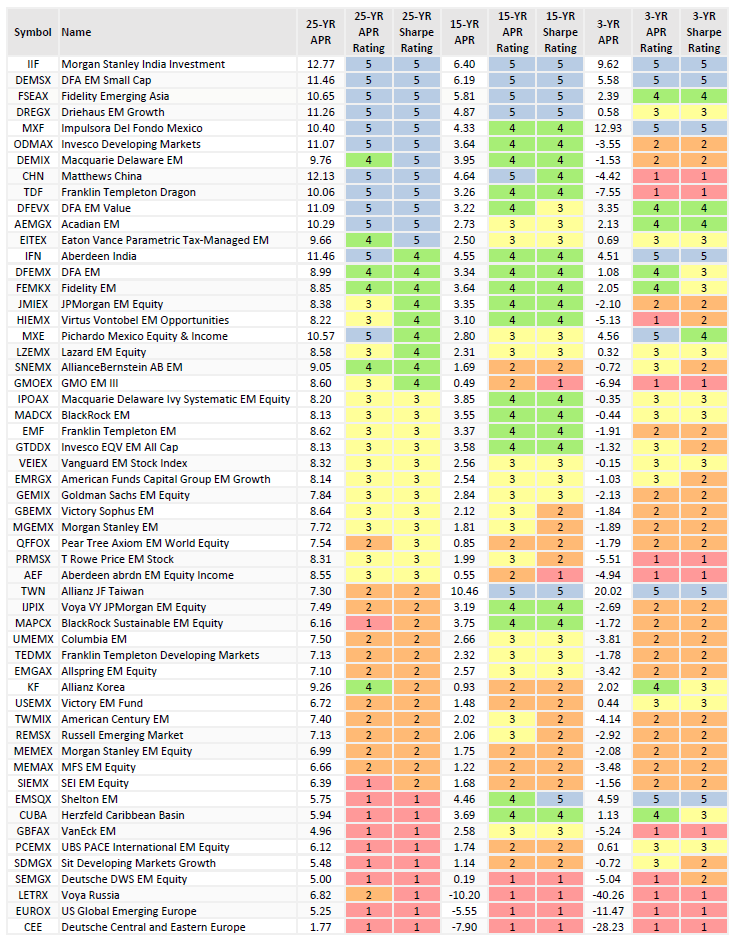

In assessing the ability of funds to weather repeated storms, we started by isolating all EM funds with a record of 25 years or more. We then looked at three metrics:

- Absolute returns since the inception of each storm. That translates to their 25-year (LTCM and beyond), 15-year (GFC and beyond), and 3-year (Covid and beyond, we hope) records

- Relative total returns. Funds with returns in the top 20% of their peer groups are shown with a blue box, green is the next 20%, and yellow is the middle 20%. Orange and red are, well, bad.

- Relative risk-adjusted returns. The same system applies: blue/green/yellow for the top three boxes.

The complete dataset is below. We’ll offer two takeaways:

-

-

Strong past performance predicts reasonable future performance. None of the 1998 standouts sagged in 2008. Few of the 1998 standouts sagged in the Covid era. Two of the top 20 funds in 1998 are noticeably sub-par now, while two more are below average.

The caveat: we can’t control for survivorship bias. If a 1998 champion subsequently burst into flames, we wouldn’t have a record of it.

-

Wretched past performance predicts ongoing misery. Bad seems to beget bad. Of the bottom 20 funds in 1998, only one has made a leap to the top tier. Almost all of the others remain mired in the land of orange (below average) and red (much below average) total and risk-adjusted returns.

The one outlier is Shelton Emerging Markets (fka Icon Emerging Markets). Shelton acquired the flailing Icon fund in June 2020. Two generations of Shelton managers have transformed it into a four-star (Investor shares) or five-star (Institutional shares) fund. Over the past three years, it has returned 7.8% annually while its average peer has lost money.

-

About 60 emerging markets funds have survived the past quarter of a century. A handful of funds have performed solidly through one crisis after the next. They are:

- Morgan Stanley India

- DFA EM Small Cap

- Fidelity Emerging Asia

- Driehaus EM Growth

- Impulsora Del Fondo Mexico

- DFA EM Value

- Acadian EM

- Eaton Vance Parametric Tax-Managed EM

- Aberdeen India

- DFA EM

- Fidelity EM

- JPMorgan EM Equity

- Virtus Vontobel EM Opportunities

- Pichardo Mexico Equity & Income

- Lazard EM Equity

Of the 15 funds that have remained consistently above average, ten are geographically diversified, and five are narrowly focused, which introduces a whole separate set of risks.

The complete roster of EM equity funds with a record of 25+ years

Funds are ranked by relative Sharpe ratio over 25-, 15-, and 3-year periods