It’s Wednesday and I spent some time this morning reading the latest IMF – Global Financial Stability Report – in which the IMF pretends to know what is going on in the world economy based on a set of erroneous assumptions about how that economy functions. But the data it provides is interesting in itself. Of interest is that fact that Australian households now have the highest debt-servicing ratios in the world as a consequence of record levels of debt and rapidly rising interest rates. What is generally overlooked in these discussions, however, are the circumstances in which the debt rose so much in the first place. In this post, I explain, among other things, how the obsessive pursuit of fiscal surpluses combined with labour market (in favour of the employers) and financial market deregulation (in favour of the bankers) in the 1980s and beyond, created the conditions whereby households could really only maintain growth in consumption expenditure by significantly increasing their indebtedness and running the saving ratio into negative territory. The legacy of that misguided shift to fiscal austerity lives on. Later in the post I make a brief comment about the Middle East and then we listen to some music.

Financial precarity in Australia

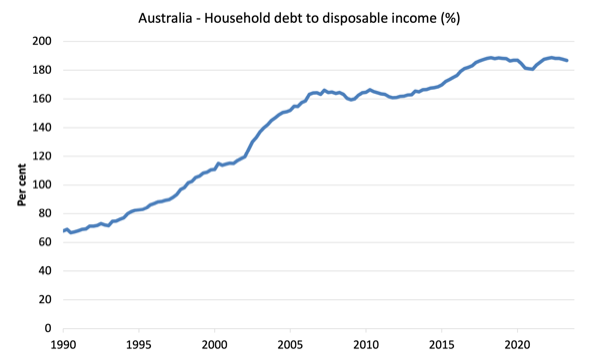

The first graph shows Australia’s household debt to disposable income ratio (per cent) since the March-quarter 1990.

The rapid rise in the 1990s up until the GFC was the product of two trends.

First, the financial market deregulation by the Federal government which opened up households to the excesses of financial engineering pushed on them by the banksters.

The financial markets knew no bounds insofar as they could push debt onto households obsessed with mass consumption.

Second, between 1996 and 2007, the federal government recorded 10 out of 11 years of fiscal surplus, which increasingly squeezed the non-government sector for liquidity.

The only reason the surpluses persisted for so long was because, in the face of that liquidity squeeze, the household sector maintained consumption expenditure growth (which maintained strong tax revenue growth) by plunging the saving ratio into negative territory for the first time in recorded history and took on significant extra debt.

Fixing balance sheets is a long process and so the current precarity, which has been exacerbated by the RBA interest rate increases since May 2022.

The IMF Report cited above notes that:

Mortgage rates have risen globally, affecting loan originations, borrower repayment ability, and housing prices. However, the effect varies across economies. Countries with a large share of variable rate mortgages and house prices still above the prepandemic average (for example, Australia, Canada, and New Zealand) recorded double-digit declines in home prices since their peak … Countries with these characteristics are likely to experience the largest effect on household debt-service ratios from further increases in interest rates

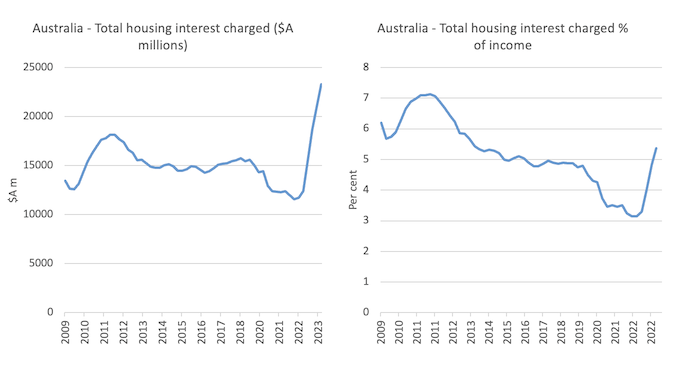

The next graph shows the rise in housing interest paid in $A millions (left panel) and as a percentage of total income (right panel).

That sharp increase in interest payments since the the RBA started hiking rates amounts to $A11,570 million which is a 99 per cent increase since the rate hikes began.

Where has that gone?

To Bank executives and shareholders.

While the lower income households carry less debt than higher income households, we know that as a proportion of income the mortgage stress is higher for lower income households.

The redistribution of income that the RBA has engineered from low to high income families as a result of their interest rate hikes is quite staggering in historical terms.

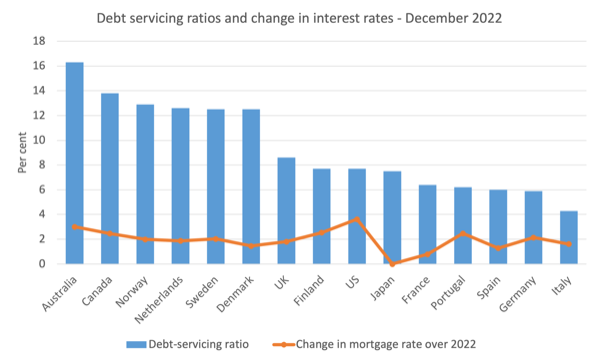

The IMF Report shows in a comparative sense that Australian households have the highest debt service ratios of the advanced economies.

The following graph covers data up to the December-quarter 2022 and shows debt-servicing ratios (per cent) for a range of nations as at the December-quarter 2022 and the Change in reference mortgage rate over 2022 (per cent).

I ranked the data in terms of highest to lowest DSR.

Since that time, the RBA has increased the rate a further 4 times (1 point).

So the DSR will be higher again.

On average, Australian households were paying 16.3 per cent of their income on housing repayments and that figure will have risen to around 20.6 per cent by now following the extra rises.

IMF modelling shows that if the mortgage rate was to rise by 500 basis points relative to its December-quarter 2022 level then the DSR for Australia would go from 16.3 per cent to 18.5 per cent.

Extrapolating that would give a DSR now of over 20 per cent.

The UK Guardian reported (July 3, 2023) on some ANU modelling that showed that “The squeeze of household budgets will probably be tightest for those who bought recently and those on low incomes such as single-parent families” (Source).

The ANU modelling showed that of the RBA increased rates by a further 50 basis points then the share of income on housing would be:

1. Lowest quintile households – 56.7 per cent (up from 36.4 per cent in 2021).

2. Second quintile households – 33.8 per cent (up from 22.4 per cent in 2021).

3. Third quintile households – 28.4 per cent (up from 17.9 per cent in 2021).

4. Fourth quintile households – 28.2 per cent (up from 18.0 per cent in 2021).

5. Highest quintile households – 20.3 per cent (up from 13.3 per cent in 2021).

The highest quintile households are also those who are almost certainly pocketing those extra interest payments noted above, which insulates them from the rise in DSRs noted above.

What is mostly forgotten in all this debate about precarity is that a significant amount of the damage was done during those years that the federal government was recording fiscal surpluses.

It was held out as a time when ‘national saving’ was rising and the government was getting the d’debt monekuy’ off its back.

But the reality is that it was a time when there was a huge shift within the non-government sector, particularly the household sector, towards debt to fund necessities – especially as wages growth was also flattened by deregulation in the labour market.

And that legacy lives on and is making the society increasingly vulnerable to financial instability as interest rates rise.

It is also making it easier to redistribute income and wealth from poor to rich and is one of the reasons inequality indexes have risen in Australia over the last three decades.

The current conflict in the Middle East

First, I abhor conflict and murder.

Second, I hate terrorism.

But the response of the Australian government to the latest conflict backed by a manic mainstream media response has been appalling.

There is not one side perpetrating violence on the other side as victims.

The Australian government has been long quiet about the abuses of Palestinians by the right-wing Israeli settlers supported by the repressive and murderous acts of the IDF.

The mainstream media rarely mention that long history of abuse, including the border checks, summary violence, walls being built across communities, houses pillaged, women raped, people murdered and the rest of it.

This analysis from Human Rights Watch (April 27, 2021) – A Threshold Crossed: Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution – provides some insights as to the lives of Palestinians in the illegally occupied territories and their homelands.

The pandering of the rabid extreme right-wing by the current PM (Netanyahu) has worsened the situation and given the settlers even more license to damage legitimate Palestinian homes and communities.

Our government fails to publicly admonish the Israelis for these abuses of human rights, but comes out immediately to condemn Hamas as terrorist organisations committing human rights abuses.

That is all I want to write about that situation.

And my views have nothing to do with anti-Semitic perspectives.

I abhor anti-Semitism too.

Music – Tony Joe White

Five years ago this month, one of my favourite artists – Tony Joe White – died (October 24, 2018) aged 75.

Soon after (October 28, 2018), the Guardian published a – Tony Joe White obituary.

I last saw him play in 2017 in Newcastle. I had seen him play several times before that.

He used an old Fender stratocaster and a Bassman 4 x 10 40 watt amp (1959 version, although he was using a reissued version last time I saw him). But the perfect combination.

He usually just played sitting alone with a drummer in the background.

And then would go crazy on guitar with distortion, wah-wah and other stuff going. It was a really special sound.

Here is TJW with his beautiful song – Rainy Night In Georgia – from a BBC show screened on September 27, 2013.

He wrote the song in 1967 and it first appeared on is 1969 album – Continued – which was his second studio album. I purchased a copy in 1970 from the Bourke Street import shop in Melbourne.

It was covered a lot (initially by Brook Benton).

On the provenance of the song, he told a journalist Ray Shasho in an – Interview – on January 17, 2014 that:

When I got out of high school I went to Marietta, Georgia, I had a sister living there. I went down there to get a job and I was playing guitar too at the house and stuff. I drove a dump truck for the highway department and when it would rain you didn’t have to go to work. You could stay home and play your guitar and hangout all night. So those thoughts came back to me when I moved on to Texas about three months later.

Appearing with him in the following BBC video, is pianist Jools Holland as part of his – Later … with Jools Holland series run by BBC Two.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2023 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.