This Tuesday report will provide some insights into life for a westerner (me) who is working for several months at Kyoto University in Japan.

The 1970s struggles go on in Kyoto

The University apartment we live in here is next door to and overlooks the now (in)-famous – 吉田寮 – or Yoshida Dormitory or Yoshida-ryo, which is run by the so-called ‘Autonomy Committee’, a student-run organisation.

The English-Wiki Page – Yoshida dormitory, Kyoto University – provides some historical and descriptive information.

There are two buildings – a new building built in …. and an old wooden structure which was built in 1913 and ‘is the oldest student dormitory in Japan’.

Adjacent is the Dining Hall, which was constructed in 1889 and is the oldest structure on campus.

The history is interesting and given my age and long associations with university campuses I can relate to the developments that have come to a head in recent years and are still to play out in Kyoto.

A Japanese tradition on university campuses was for the university authorities to hand over the administrative responsibilities of running the student accommodation (these dormitories) to the students, who formed committees and self-regulated.

Here is a view from my balcony of the old dormitory first, then the dining hall.

In the early 1970s, when student activism was causing ripples all around the globe, the Japanese Ministry of Education in liaison with the top brass at the universities decided that the so-called ‘Marxist-Leninisn’ was making them uncomfortable, they singled out the dormitory system as being the culprits.

They considered these living quarters to be breeding grounds for anti-authoritarian movements and to be “hotbeds for various kinds of conflict”.

They labelled the students ‘Marxist Leninists’, which may have been tru, and decided to end the autonomy arrangements and close the dormitories.

The students at the Yoshida-ryo refused to leave after the University bosses issued an ultimatum in 1986.

Several attempts then followed to force the issue but the students dug in.

Fast track to recent times.

On December 19, 2017, the University told the autonomy committee that they were closing the dormitories and everyone had to leave by September 2018.

The issue is sometimes characterised as being about the heritage value of the buildings, which carries some truth.

But I have been talking with the students who still live there now and for them it is about maintaining the core of the Japanese student movement, which flourished in the 1979s, but has found it harder to remain solid in the neoliberal era.

There is also the question of housing costs – the dorms are very cheap for students.

Anyway, since that 2017 ultimatum, the matter is now in the Kyoto District Court for resolution and hearings were held last week I believe with a decision before the end of the year.

Here is the – 吉田寮を残したい!京大は裁判をやめて!(2023年開始版 (which broadly translates to ‘I want to keep the dormitory. Kyoto University should abandon the trial’), which provides more context.

I am with the students.

However, some of my research colleagues also tell me that if there is a major seismic event (which is very likely), the buildings will not survive anyway, and casualties would be expected.

But the struggle against university authorities takes me back to the 1970s when I was a student at Monash University in Melbourne and the campus was very active.

We even forced an Australian prime minister one day in 1976 to seek refuge in a toilet to avoid the student anger.

You can read about that in this article (September 4, 2012) – Once were campus warriors

Here he is being rescued by the security forces.

Good times.

Yuka

When I am in Kyoto, I always head down the Kamo River which provides fast bike transit without traffic north-south; places to sit and think while listening to the water flow; places to walk and watch local happenings; and, of course, a magnificent place to run early in the mornings where one can traverse many kms without traffic.

Down towards the city centre between the – 三条大橋 (Sanjō Ōhashi bridge) – and the – 四条大橋 (Shijo-ohashi Bridge) – on the Western side of the river, one observes these structures (terraces) that protrube out the back of the old wooden buildings along the river (and the drainage canal between the river and the houses.

The former bridge, by the way, was the final bridge before travellors entered Kyoto from the famous route from Edo (Tokyo) to the Imperial capital, the – Tōkaidō (road) – or Eastern sea route.

Here is what I am referring to:

I have often wondered about them given there concentration in this part of the river side.

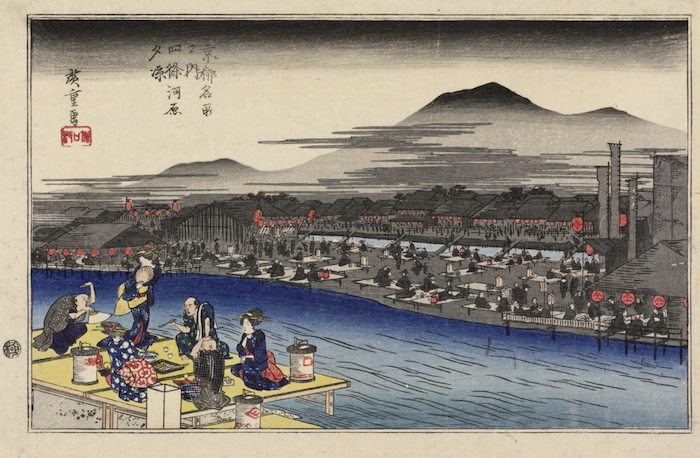

In my study of the work of the woodblock artist – Utagawa Hiroshige – who I have mentioned here before, I came across his 1834 woodblock print in his series ‘Famous Views of Kyoto’. which was entitled ‘Enjoying the Cool of Evening on the Riverbed at Shijō’.

Shijō is the area near one of the bridges I mentioned above.

I then went to one of my favourite places – International Research Center for Japanese Studies – which is located in Kyoto, to do some further research.

This is a fabulous place and a partnership between several universities and funded by the government.

It provides a wealth of material relating to history, culture and the humanities in general.

Anyway, I learned a lot about the history of the so-called Nouryou-Yuka along the Kamo River.

During the – Edo period (1603 to 1868) – which marked the end of the civil wars and a period of peace and economic growth, the river side of the Kamo became a popular recreation space (as it is now).

The bridges were rebuilt and a range of tea houses and seating emerged.

All frequented, of course, by the wealthy citizens of the town and visitors with means.

The Gion Maiko (Geisha) district evolved nearby.

Soon, the authorities decided that the seating had become random and overcrowded and strict rules were drawn up and enforced, which places limits on the size and location of the seating decks.

The seating decks become institutionalised during the – Meiji era (1868-1912) – and the Yuka terraces or decks became very popular in the summer months, when Kyoto gets very hot.

Here is an historical photo from the International Research Center for Japanese Studies of some finely dressed woman enjoying the shade and some tea on a Yuka deck below the Sanjō Ōhashi bridge (now gone).

I learned that in 1894, all the decks on the Eastern side of the river were demolished to allow the construction of the Kamo River Canal, which is a drainage system.

The railway was also extended down the east side some time after that.

More recently, during the – Shōwa era (1926-1989) – all semi-permanent decking was made illegal, in part, because of fears of floods.

The river really rages after heavy rain.

In 1934, the – 1934 Muroto typhoon – proved the authorities right and wiped out many of the Yuka terraces.

The creation and design of these decks is now strictly regulated, which answers the question I often asked as I ran past them in the morning – why are there so few and only on the West side.

What’s this?

This is the draft book cover for my next book, which will be launched in Tokyo on November 17, 2023. It is co-authored with Professor Satoshi Fujii and carries the title ‘Theory of active fiscal policy in the era of inflation’.

I will have more to say about that soon including details of when and where the event will be held.

And what’s this?

Look out for Friday of this week.

MMTed has something new happening!

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2023 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.