This is an election year in the UK and unless something dramatically changes, the Labour Party will be in power for the next term of Parliament and will ahve to manage a poly crisis that they will inherit from 40 or more years of neoliberalism. Note, I don’t confine the antecedents to the Tory period of office since 2010 because the decline started with James Callaghan’s Labour government in the 1970s and then just got worse during successive periods of Labour and Tory rule. During that long period, there has been no shortage of economists and public officials predicting that the financial markets would soon reap chaos as a result of the public debt levels being ‘too high’ (whatever that means). The most significant chaos came in 1992 when Britain was forced out of the European exchange rate system, which it should never have joined in the first place. While all these economists are now pressuring the likely next British government to pull back on their promises to ‘assuage’ the financial markets, there is not even a scintilla of evidence to support their predictions of doom. And the Labour party leaders are too stupid to realise that.

For new readers, we should always start by noting that all this discussion is rather pointless given that the UK government never needs to issue any debt at any maturity in order to spend the currency that it alone issues and spends via computer keystrokes.

The fact that the UK government continues to do so is a hangover from the Post World War 2 fixed exchange rate system, which effectively ended in August 1971, when President Nixon cancelled the gold convertibility for US dollar holdings.

Of course, given that the public are largely ignorant of what debt is, how it is issued and the consequences of issuing it, politicians use it as a powerful leverage tool to influence public policy.

They can always avoid spending by telling the public that they don’t want to ‘increase the taxpayers’ debt burden’ or oppositions can accuse a government of irresponsible profligacy for ‘running up the debt mountain’.

Neither statement/accusation has the remotest validity in terms of monetary dynamics but works as a powerful political weapon.

If the public understood what the debt was all about then the weapon would become irrelevant in terms of influencing public policy choices.

I have written about this in many blog posts but this one covers most of the issues and recounts an interesting Australian story I was involved in more than 20 years ago, which really gave the game away – Market participants need public debt (June 23, 2010).

The UK Guardian article over the weekend (January 24, 2024) – Watch out, Rachel Reeves: the old guard is ganging up on your borrowing ambitions – reports about how hard it will be for the Labour government to break out of the cycle it found itself in from the 1970s when it first started to articulate the ‘appease the financial markets’ narrative.

The next British government has to urgently break out of the ‘sound finance’ trap because the challenges facing it are immense.

There is decayed infrastructure to be fixed and expanded.

Privatisations that have gone badly wrong in essential services need to be reversed.

Local governments have to be revitalised with extra funding.

The hospital system and related NHS needs significant injections of capital after years of outsourcing and privatising attrition.

Then there is the climate issue – oh that!

The problem is that the Labour Party thinks it is clever to lie and claim they can invest heavily in all sorts of things yet, at the same, time meet some ridiculous self-imposed ‘fiscal rules’ that highly constrain what they can do.

I have written extensively about the fiscal rules that the Labour Party brought to the last general election – the so-called

This blog post contains a number of links that sequence my interactions with British economists on the topic – The British Labour Fiscal Credibility rule – some further final comments (October 23, 2018).

You can also find some of them by using this – Search Link.

The so-called ‘Fiscal Credibility Rule’ that the Labour Party took to the last election was a classic submission to the neoliberal pressures and amounted to a surrender by the Labour Party to the conservatives and corporate types who use government debt as a form of corporate welfare but want governments to cut any income support to the disadvantaged.

At the time, I was significantly vilified by the economists who had framed the rule for the Labour Party because I exposed, not only its ideological origins, but also demonstrated that it was internally inconsistent with proposed Labour policy and would certainly fail to be met.

While denial reigned supreme, I also noted in the last few weeks of the campaign, the Party altered the rule to try to reduce the inconsistencies that I had pointed out.

These changes were made without any acknowledgment that their arguments in supporting the first version of the Rule were defective.

Anyway, the new shadow chancellor, Rachel Reeves has not seemed to learn anything from that period and regularly sprouts forth about their new rule, which I have not yet seem formally specified but seems to resemble the old rule.

The UK Guardian article (cited above) confirms that the establishment economists snd financial market types are already running the ‘debt mountain’ narrative and that Reeves is steadily watering down the ambitions of a new Labour govenrment should they be elected.

A few weeks ago, the Labour Leader told the British people during a radio interview that the previous promises to invest £28 billion per year on climate change investment projects was now just an ‘ambition’ because the “fiscal rules come first”, referring to the commitment to ensure that public debt to GDP ratio falls in the first five years of taking office (Source).

The reaction was clear – their promise to generate electricity by 2030 without the use of fossil fules would be very hard to keep without the investment now.

The so-called ‘Green Prosperity Plan’ requires massive investment now from government

So the ‘fiscal rules’ first and the older ‘fight inflation first’ are a continuation of the same neoliberal nonsense that my profession infests the public debate with.

The UK Guardian article concluded that:

Such is the weight of argument against Reeves that Labour has scaled down its ambitions, and the investment plan will only reduce, rather than reverse, the dramatic fall in public investment as a proportion of national income mapped out by the current administration over the next five years.

Bad luck Britain.

A pox on both sides of politics.

The UK Guardian article, of course, while reporting the attacks of economists on the political class over debt, also perpetuates the same logic that these economists use.

It claims that in the lead up to the 2010 election a similar attack on Labour fiscal policy was made but that:

… there was a clear case for borrowing at historically low interest rates to invest in Britain’s infrastructure and its education, health and welfare systems to raise productivity and national income.

This is the ‘deficit dove’ argument that if interest rates are low, the government can invest but not otherwise (as now).

The point this avoids (or doesn’t know) is that the central bank, a part of government, can control bond yields whenever it wants to by simply buying all the debt that is issued.

Moreover, the government can spend beyond its tax revenue without issuing debt any time it wants.

That should be the progressive narrative rather than conceding that sometimes it is okay to investment in public infrastructure that will advance public benefit but other times it is not.

A major intervention in the public debate came earlier this month, when the boss of the Debt Management Office in the UK (which issues the debt for government), was reported in the Financial Times (January 4, 2024) – UK debt chief warns excessive borrowing risks investor backlash – as claiming the government has to be “wary of a backlash in financial markets” should it borrow too much.

He claimed that “the job of issuing bonds was getting harder and investors might act as a restraining influencing on fiscal policy”.

The latter point is obviously just a lie – the government can ignore the ‘investors’ if it wants to by turning off the corporate welfare machine that is the bond issuing charity scheme.

But what about the first point – that it is getting harder to issue bonds?

Here is some data on the bid-to-cover ratios.

I wrote about these ratios in these blog posts among others:

1. D for debt bomb; D for drivel (July 13, 2009).

2. Bid-to-cover ratios and MMT (March 27, 2019).

The bid-to-cover ratio is the ratio of the total amount of bids to the amount on offer at a gilt auction or a Treasury bill tender.

So if it is exactly 1, then there are the same number of bids (in currency terms) as there is debt up for auction.

Below 1 – which is referred to as an ‘uncovered auction’ – there are a lack of bids and the government either has to sell less in that auction or the central bank will just hoover up the shortfall.

No drama either way.

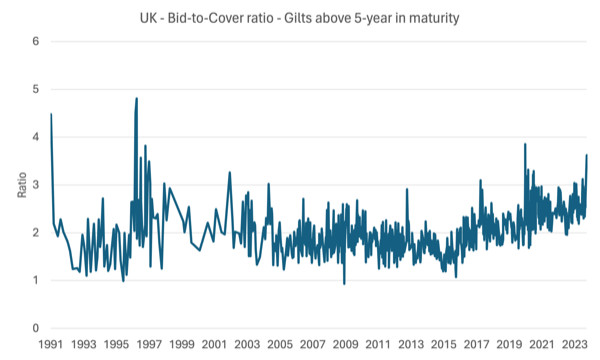

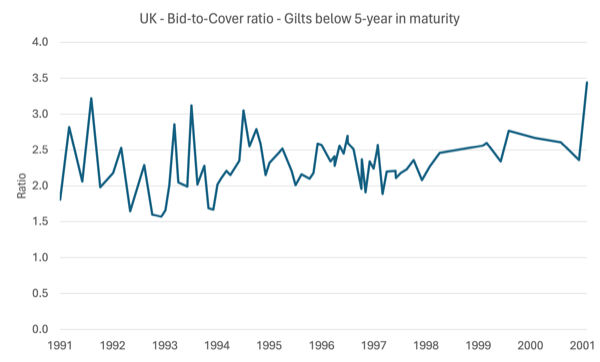

The following graphs show the bid-to-cover ratio for all British Treasury Gilts from the auction on April 24, 1991 to the most recent auction on January 10, 2024, excluding the Index-linked Treasury Gilts.

Excluding the index-linked Treasury Gilts actually makes it harder to prove my point.

I divided the data into short-run debt issued (less than 5 years in maturity) and the longer-term gilts (above 5 years in maturity).

91 per cent of the non-index linked Gilts issued were for periods longer than 5 years.

The first graph is the longer-term debt and the second graph the rest.

For the longer-term issues, the bid-to-cover ratio fell below 1 on two occasions:

1. September 27, 1995 for a 7½% Treasury Stock 2006 issue – ratio was 0.99.

This Bank of England report – The gilt-edged market: developments in 1995 – helps us understand what happened in that period.

Prior to September 1995, long-term yields on British government gilts were falling after the financial market turmoil in European currency markets over the Summer of 1992, which culminated for Britain with Black Wednesday (September 16, 1992) and its exit from the European exchange system.

We know that there were “political uncertainties in the United Kingdom and expectations of interest rate reductions in the United States” over the 1995 Northern Summer.

Barings Bank had collapsed in February of that year.

Gilt prices were rising over that period as the “domestic political factors became less important” and the September gilt auction ended uncovered only to recover strongly in October (bid-to-cover ratio of 2.0).

The Bank of England notes that:

The September auction of £3 billion of a new ten-year benchmark for 1996 was the first gilt auction to be uncovered (albeit only very marginally so), and the tail of seven basis points was the longest then recorded. Notwithstanding the market turbulence in which the auction took place, it was disappointing that ‘when issued’ trading in the run-up to the auction, which is normally seen as an effective mechanism for price discovery, failed to find a level at which the auction would clear.

But nothing to worry about.

2. March 25, 2009 for a 4¼% Treasury Gilt 2049 issue – ratio was 0.93

This auction was held in the depths of the GFC and the government was trying to issue 30-year gilts in a very uncertain market.

This auction was followed by the April auctions were the long-term debt issues had bid-to-cover ratios of 2.23, 1.59, 1.82 and 2.11 for various maturities.

The Debt Management Office, which took over responsibility for the management of government bonds in April 1998 from the Bank of England reported in its – Debt and reserves management report 2009-10 – that:

In conclusion, as measured by the bid-to-cover and auction tail, gilt auction performance in 2008-09 has remained strong overall.

They attributed the uncovered auction on March 25, 2009 to “volatile gilt market conditions”.

This was a time that the Bank of England began its asset purchashing program (QE), which raised uncertainties.

But overall a blip.

Overall, the average bid-to-cover ratio for the debt over 5-years was 2.09.

However, in recent years (since the start of 2022) the ratio has averaged 2.53.

Since 2023, the average has been 2.62 and the most recent auction (the first) for 2024 it was 3.62 on 20-year gilts.

It is hard to find any justification for the boss of the DMO’s conclusion that “the job of issuing bonds was getting harder”.

The bid-to-cover ratios for the shorter-term debt are clearly always well above 1.50.

What all that means is the ‘investors’ in the financial markets can’t get enough of the primary gilts issued by the British government to match (not finance) their fiscal deficits.

The corporate welfare is is high demand.

Conclusion

The latest doom leverage item used – in a long-line – is the so called “ill-fated ‘mini’ Budget of September 2022 which sent the gilt market into meltdown”.

That is a strange conclusion because the bid-to-cover ratios averaged 2.25 through September and October last year even if yields rose somewhat.

My assessment of that period was that the financial markets, always seeking to bluff the government, realised they could make threats to stop buying the debt because the government resolve was so weak.

If the financial markets can dominate, why has the Bank of Japan been able to hold firm over three decades to its much-criticised policy, which continually thwarts the short-sellers.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2024 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.