There is a consistent undercurrent against Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) that centres on whether we can trust governments. I watched the recent Netflix documentary over the weekend – American Conspiracy: The Octopus Murders – which reinforces the notion I have had for decades that there is a dark layer of elites – government, corporations, old money, criminals – that is relentlessly working to expand their wealth and maintain their power. Most of us never come in contact with it. They leave us alone and allow us to go about our lives, pursuing opportunities and doing the best we can for ourselves, our families and our friends. But occasionally some of us come into contact with the layer and then all hell breaks loose. The documentary started with a journalist being killed because he had started penetrating an elaborate conspiracy which began with the US Department of Justice stealing software from a company and then multiplied into money laundering scams (Iran contra), murder of various people who got in the way, and went right up to Ronald Reagan, George Bush and other senior politicians. It was a sobering reminder. I will write more about this topic in the upcoming book we are working on (with Dr L. Connors) but I was reading some articles over the weekend (thanks to Sidarth, initially) about the way the MGNREGA in India, which is a public job guarantee-type scheme has been corrupted as the ideology of the government shifted and it bears on this question of trust.

Even progressives have, over the years, railed against the idea of a Job Guarantee scheme using the argument that the government will use the structure to undermine career public sector employment and dumb down jobs to minimum wage levels.

They say we cannot trust our politicians not to take advantage of such a framework to cut wages and conditions.

So, as a response – what they think is a protective strategy to avoid such an attrition – they proffer a basic income guarantee, which they claim would protect workers from capricious governments.

I am always bemused by this general argument and the basic income specific version of it.

First, a basic income doesn’t protect workers at all because usually those in need of a stable income have become unemployed and basic income advocates (the ‘I just want to do my art’ cohort) accept the fiction that governments are constrained in their capacity to create work and so should provide an income instead of a job.

I have always rejected that logic because it is clear that governments can always create sufficient jobs to fully employ those who seek work.

I accept that governments that surrender their currency sovereignty – for example, the 20 Member States of the Eurozone – are sometimes not able to do that because they use a foreign currency (the euro) and must tax and/or borrow in order to spend.

That alone, in my view, is sufficient reason for leaving such tied currency arrangements, especially when the currency issuer in that system (the ECB) is anything but benign and has demonstrated after the GFC their willingness to destroy the viability of a Member State (Greece) to maintain the ideological bias driving the dynamics of the monetary system.

Second, I am always bemused by the trust argument.

The propensity for ideological shifts to occur when the flavour of the party in power shifts is always there and there are countless examples of good policy being tainted when governments changed.

The Tory assault on the British NHS is a stark example.

The Conservative government knew it would be politically impossible (just about) to scrap the NHS completely given its embedded cultural presence.

So they have sought to destroy the system while still maintaining they are committed to the NHS by funding cuts, oursourcing, privatising elements and more.

Does that mean the NHS when first introduced by Clement Attlee’s Labour government in 1946 was a bad idea?

Should progressives have opposed the NHS then because they would not have been able to trust future governemnts not to alter it and use the structure to pursue policies inimical to the foundational aspirations?

I don’t think so.

In Australia, the national unemployment benefits scheme was first conceived as a welfare measure designed to provide some income support for the short periods that workers in those days might experience unemployment.

It was part of a more comprehensive strategy which prioritised job creation so as to maintain full employment and well-funded education and skill-develpment initiatives (such as the broad apprenticeship schemes within the public sector) to ensure workers were prepared for the jobs that were created.

But, it also provided income support in the event that a worker found themselves unable for a short time to find work.

The income support was never designed to be provided for more than a few weeks.

Since the 1970s, as governments abandoned their commitment to that comprehensive strategy and started to deliberately create unemployment as a misguided strategy to ‘fight inflation first’, the unemployment benefits system has been maintained by corrupted.

It was obvious that the rising levels of unemployment would present the government of the day with a political problem.

To divert attention from their role in creating that unemployment, governments started to vilify the unemployed in order to convince us that this cohort was different to the rest of us ‘hard working’ souls – they were lazy, unmotivated and corrupted by the income support provided to them.

So the policy progressively became punative – with all sorts of incomprehensible and ineffective work tests and compliance measures.

As the duration of unemployment, on average, rose, it became obvious that the income support was inadequate but successive governments defended the low payment on the grounds that they didn’t want the unemployed to ‘live on’ the payment – they wanted them to feel the desperation of poverty and search harder for work.

And now we have an unemployment benefit payment that is well below any acceptable poverty line and the recipients forced to interact with sociopaths in the privatised employment services sector that seek profit rather than the satisfaction of providing help for the disadvantaged.

Given this shift over time, does that mean that the government was wrong to introduce such an income support system?

I don’t think so.

I could continue but you surely get the drift.

The ‘we don’t trust the government’ stance is a dead-end – because logically it leads one nowhere.

Although, I think mostly this progressive distrust of government leads us to even more neoliberalism rather than less.

In general, there is no government policy that is not susceptible to ideological shift.

Does that mean we should oppose government intervention?

Because our politicial class is capable of behaving like the characters in the Netflix documentary I mentioned above (which is an extreme example), do we eschew strategies designed to improve public policy?

Where else can we go?

Nowhere!

A progressive agenda must not accept neoliberal constraints (such as when the BIG crowd surrender to the notion that governments cannot reduce unemployment).

Once we surrender to those propositions the game is over.

Why we are in this parlous state now is because progressives abandoned the macroeconomic contest in the 1970s when they were told by Monetarist economists that the government was now weaker than the global financial markets and had to ensure policies were consistent with the objectives of those markets.

The shift to ‘sound finance’ was the manifestation of that surrender and progressives were diverted into all sorts of other agendas (identity, methodology etc) which left the main game – macroeconomics – in the hands of the neoliberals.

Yes, we might not be able to trust our politicians.

But that means we have to have a multi-pronged strategy not only to develop and propose progressive policies that reflect a valid understanding of the capacities of the currency issuer (that is, Modern Monetary Theory) but also to work on praxis – how do we improve the quality of our political representatives.

That requires activism at the local level.

India’s – The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act 2005 (MGNREGA) – is being corrupted by neoliberalism

I have followed this program since its inception in 2005 and monitored the way in which it has evolved.

Here are some selected blog posts on the topic which began in 2009.

1. India’s national employment guarantee hampered by supply constraints (March 28, 2016).

2. Large-scale employment guarantee scheme in India improving over time (September 1, 2014).

3. Employment guarantees should be unconditional and demand-driven (June 25, 2012).

4. Employment guarantees in vogue – well not really (November 18, 2009).

5. Employment guarantees in developing countries (May 10, 2009).

The MGNREGAS was introduced to bridge the vast rural-urban income disparities inequality that have emerged as India’s information technology service sector has boomed.

Essentially, the growing jobs boom in the urban areas created massive incentives for poor rural workers to move into the cities in search of a living.

There were two negative consequences of this.

First, the urban centres could not cope with the increased populations – housing, transport, public services, etc – were inadequate to meet the demands of the rising populations.

Second, the exit of tens of thousands disrupted the continuity of the rural areas.

The answer was to create job opportunities in the rural areas, where they had been extremely scarce to provide a minimum standard of living for those who stayed and were prepared to perform manual work for a certain guaranteed number of hours per year. That was the main motivation for the introduction of the scheme.

The – The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act 2005 – enshrined the ‘right to work’ into legislation.

The program began in February 2006 and is administered by the Ministry of Rural Development.

It initially guaranteed 100 days of minimum-wage employment on public works to every rural household that asks for it.

The adults in the program were required to undertake unskilled manual labour at the legal minimum wage.

Once an adult applied for work, the scheme was compelled to employ them within 15 days or pay unemployment benefits.

Women were guaranteed at least 30 per cent of the work administered under the program.

Local communities were empowered to have input into the selection and design of the jobs with local government planning and implementing the work activities.

You can also learn about it – HERE.

The initial design of the MGNREGS was far from the Job Guarantee ideal that I have developed.

Remember the features of the Job Guarantee are designed to ensure the simultaneous achievement of full employment and price stability and exploit the currency monopoly held by the national government.

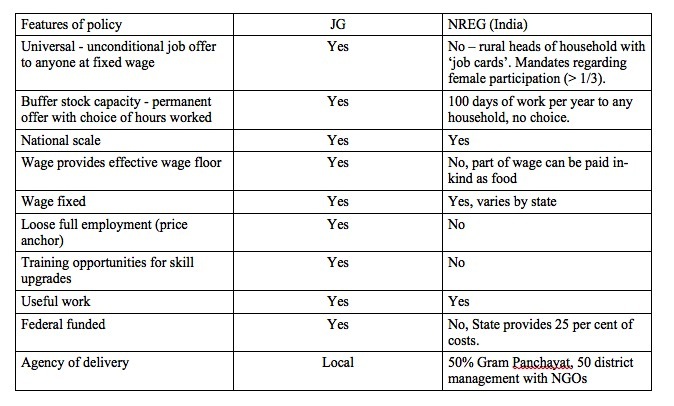

I provided this Table, based on our research work at the time, which provides a brief comparison of the desirable properties of a buffer stock employment scheme (Job Guarantee) and the MGNREGS.

The MGNREGS began life as a cut-down version of the Job Guarantee, in the sense, that the latter is unconditional and demand-driven (that is, the government employs at a fixed price up to the last person who seeks work) whereas the MGNREGS is conditional and supply-driven (that is, the government rations the scheme according to some rules – number of jobs, hours of work or some other rationing device).

You can readily appreciate that the underlying MMT which drives the JG conception is missing from the MGNREGS.

The scheme does not provide a permanent job offer which means there is no ‘buffer stock’ capacity available in India.

The lack of universality of the programs means that unemployed workers are unable to freely enter and exit the program.

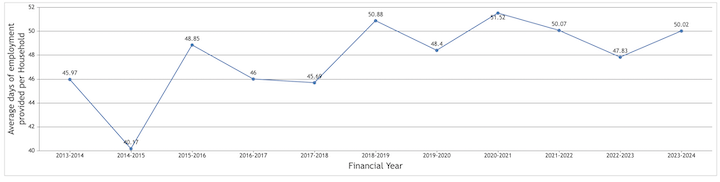

It was also obvious from the data that the promise of 100 days work per year was an illusion in the MGNREGS.

Here is the latest data from the Ministry showing the average day of employment provided per household by the program.

A lack of universality is not the only way that the MGNREGS fails to serve the buffer stock role.

In the MGNREGS, sub-national governments, which are revenue-constrained, contribute to the investment outlays of the scheme, which limits its scope to respond to the demand side.

Also, given the wage arrangements (some of the wage can be paid in food) the MGNREGS did not provide a comprehensive nominal price anchor.

By paying a minimum wage to all workers, the Job Guarantee creates ‘loose full employment’ – in the sense it places no pressures on the price level in its own right.

It can also be used to discipline the inflation process by redistributing workers to the fixed price sector.

There was no such capacity in the MGNREGS.

Finally, MGNREGS provided no training capacity.

The ideal Job Guarantee would integrate skills development into the unconditional job offer and thus build dynamic efficiencies into the economy and provide the least-advantaged workers income security but a ladder to move to higher productivity jobs in the future.

However, having said that, the Indian program was a step in the right direction.

Until it was not!

The initial program was introduced by the United Progressive Alliance (UPA), which was elected at the 2004 general election and comprised a number of Left-wing parties who came together to form a majority.

It held power until 2014 and was of a ‘centre left’ persuasion, even though its largest early contributor of MPs was the Left Front, which was a collaboration between the Communist Party, the Revolutionary Socialist Party, and the Marxist Forward Bloc, to name some of the member organisations.

In 2014, it lost power to the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which has been the major representative of the religious right since the 1950s.

The change in government was significant for the program.

The – LibTech India – organisation, uses “a rights-based framework” to analyse “different policies, trying to make them transparent and disseminating data about them to those who can use the information to make the state accountable to them.”

In particular, it provides a fantastic database for assessing the MGNREGA program.

I am working through the myriad of recent publications provided by LibTech India.

Their work has been written about in these articles:

1. MGNREGA Sees Record Job Card Deletions in 2022-23 Due to ‘Violation in Procedure’, Finds Report (The Wire, October 20, 2023).

2. The advent of ‘app-solute’ chaos in NREGA (The Hindu, June 25, 2022).

The first article cites the work of LibTech India, which found that “A research organisation has noted a record increase in the deletion of job cards for the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) database last financial year of 2022-23.”

This has been brought about by technical changes to the system, which made it much harder for the workers to gain access to the work.

This recent article from The Wire also provides some insights to the changes that have occurred in the system: Sharp Fall in Number of MGNREGA Workers in Telangana After Union’s Push Towards Aadhaar-Based Pay (The Wire, February 6, 2023).

It is clear that the current neoliberal government is manipulating the system to make it harder for workers to qualify.

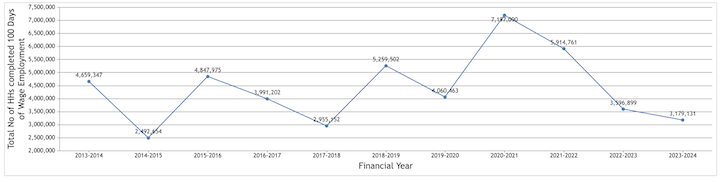

This graph shows the number of households completing 100 days of work:

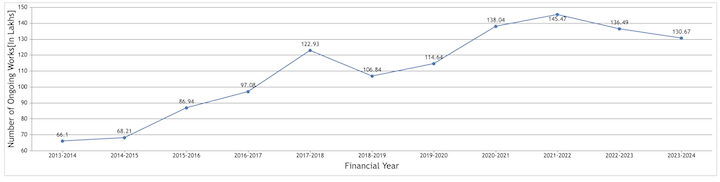

And this graph shows the number of ongoing projects under the scheme:

It is clear that the blip provided by the pandemic is gone and the scheme is in retreat – a deliberate retreat.

In the latter article cited we read:

The modified Aadhaar-based payment system (ABPS) for workers under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Programme (MGNREGA) made compulsory from January this year has rendered lakhs of workers ineligible for the scheme.

While the figure of deletion at the national level, according to a rough estimate, is 7.6 crore, in Telangana, about 18.04 lakh workers have been deprived of work in spite of holding job cards issued under the programme.

Remember a ‘crore’ is equal to 10 million.

This article (October 20, 2023) – Rule flout stink in job card purge; glare on 5 crore NREGA deletions in a year – reported that LibTech India:

… cited the huge jump in deletions in 2022-23 to suggest a deliberate paring of numbers by state governments, which faced pressure from the Centre to ensure that MGNREGA wage payments were made through the cumbersome Aadhaar Based Payment System (ABPS).

The pay system change is a cruel technical device that the government claims is to reduce corruption (“bogus cards and fake muster rolls”) but has had the effect of shrinking the program dramatically.

It reminded me of the Robodebt system in Australia, which a Royal Commission has concluded recently was illegal from the outset but which forced many workers to repay millions of welfare payments to the federal government which they did not actually owe, with some committing suicide from the stress.

I will write about the continual undermining of this program in more detail in other posts.

The point is this: Yes, the scheme is now being manipulated by a government which ideologically is opposed to such government intervention and is infested with ‘sound finance’ types who think there role is to ‘save’ money rather than advance the prosperity of the people, particularly those at the bottom of the heap.

So the initial scheme is undergoing dramatic change that undermines its original purpose.

Does that mean that because those who supported the UPA and couldn’t trust the BJP politicians were wrong to support the introduction of the scheme in the first place?

I think not.

So these progressive complaints about the idea of a Job Guarantee, as being dangerous because conservative politicians will turn it into a nightmare of oppression are misplaced.

Conservative politicians can make any program a nightmare – however progressive it was at the start.

Conclusion

Our challenge is to improve our political class so they better represent us faithfully.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2024 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.