Most of the time, people are subject to state taxes in the states where they live and/or earn their income. So when moving to a lower-tax state or another, their income tax burden likewise shifts to the new state along with them. Which is, for example, why so many people opt to move to lower-tax or no-tax states like Florida or Texas in retirement, where they can enjoy lower state income taxes and preserve more of their retirement savings for use by themselves or their heirs.

But like many rules, there’s an exception: When a person working in one state defers some of their income, then moves to a different state (where they ultimately receive the income), that income can in certain cases be taxed by the first state (where they worked when they earned the income) even when the person now lives in a different state. In other words, moving to a lower-tax state won’t always result in paying lower state taxes with particular types of income.

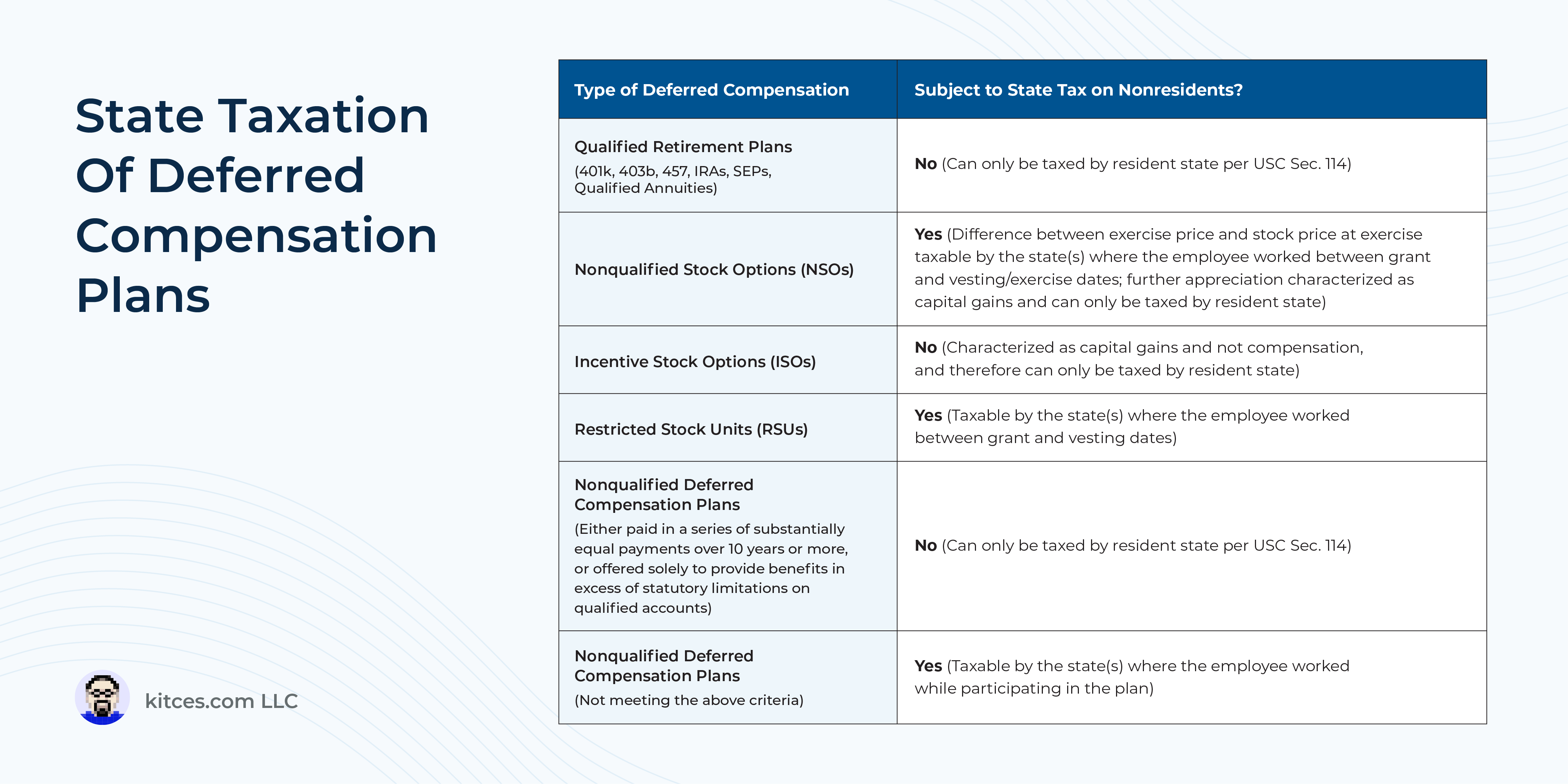

Specifically, USC Section 114 defines certain types of “retirement income” that can only be taxed by the states in which a person resides, which include qualified employer retirement plans and IRAs as well as nonqualified deferred compensation plans that are either paid out over a period of at least 10 years or structured as an excess benefit plan. However, other types of deferred income, including equity compensation plans like stock options and RSUs (which generally aren’t taxed until after a multiyear vesting period) and nonqualified deferred compensation plans that don’t meet the specific criteria above, can still be taxed by the state in which that income was initially earned, even after the employee moves to a different state.

For advisors of employees who want to minimize their state tax burden in retirement, then, understanding the different types of deferred income they may be receiving – and how (and by which states) it will be taxed – can help to recognize planning opportunities that help ensure the client’s goals of lower taxes are actually met. For example, some strategies around employee stock options plans, such as utilizing Incentive Stock Options (ISOs) or making an 83(b) election on Nonqualified Stock Options (NSOs), cause income from those options to be recognized primarily as capital gains, which would be taxable only in the state where the employee lives when they actually sell the underlying stock. And for employees with access to nonqualified deferred compensation, confirming that the plan’s benefits pay out as a series of substantially equal periodic payments over at least a 10-year period ensures that they meet the definition of “retirement income” under Section 114. (And because nonqualified deferred compensation is traditionally offered only to executives and other key employees, those employees may be able to influence how the plan is set up to begin with to ensure the best tax treatment!)

The key point is that when someone moves to a different state for tax purposes, sometimes the move itself isn’t enough on its own to accomplish that goal, and more careful planning is necessary to see meaningful tax savings when deferred compensation is part of the financial picture. Which ultimately means that advisors with a deeper knowledge of the state tax treatment of deferred income can help make sure that their clients’ expectations of lower state taxes in retirement match up with the reality.