Today (March 27, 2024), the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released the latest – Monthly Consumer Price Index Indicator – for February 2024, which showed that the annual inflation rate steadied at 3.4 per cent. Today’s figures are the closest we have to what is actually going on at the moment and show many of the factors that drove the sudden burst in inflation are now abating and the current factors that are significant are more to do with abuse of market power than overspending or excessive wage demands. Significantly, if we look at the All Groups CPI excluding volatile items (which are items that fluctuate up and down regularly due to natural disasters, sudden events like OPEC price hikes, etc) then the monthly inflation rate was zero and the annualised rate over the last six months is 2.5 per cent – which is in the middle of the RBA’s inflation targetting range. If we take the annualised rate of that series, over the last three months, then the inflation rate is 2 per cent, at the bottom of the RBA’s range. The general conclusion is that the global factors that were responsible for the inflation pressures are abating fairly quickly as the world adapts to Covid, Ukraine and OPEC profit gouging. This inflation was never about overspending.

The latest monthly ABS CPI data shows for February 2024 that:

- The All groups CPI measure was steady at 3.4 per cent.

- Food and non-alcoholic beverages rose by 3.6 per cent (4.4 per cent in January).

- Clothing and footwear 0.8 per cent (0.4 per cent in January).

- Housing 4.6 per cent (4.6 per cent in January). Rents (7.6 per cent cf. 7.4 per cent).

- Furnishings and household equipment -0.3 per cent (0.3 per cent in January).

- Health 3.9 per cent (3.9 per cent in January).

- Transport 3.4 per cent (3 per cent in January).

- Communications 1.7 per cent (2 per cent in January).

- Recreation and culture 0.4 per cent (-1.7 per cent in January).

- Education 5.1 per cent (4.7 per cent in January).

- Insurance and financial services 8.4 per cent (8.2 per cent in January).

The ABS Media Release (February 28, 2024) – Monthly CPI indicator rose 3.4 per cent in the year to February 2024 – noted that:

Annual inflation was unchanged in February and has been 3.4 per cent for three consecutive months …

The most significant contributors to the February annual increase were Housing (+4.6 per cent), Food and non-alcoholic beverages (+3.6 per cent), Alcohol and tobacco (+6.1 per cent) and Insurance and financial services (+8.4 per cent). …

Rent prices rose 7.4 per cent in the 12 months to January, reflecting a tight rental market and low vacancy rates across the country …

Although Taylor Swift performances saw hotel prices rise in Sydney and Melbourne, elsewhere accommodation and airfare prices fell in February due to the end of the peak travel during the January school holiday period.

So a few observations:

1. The inflation situation has stabilised and will steadily decline over the next several months.

2. Significantly, if we look at the All Groups CPI excluding volatile items (which are items that fluctuate up and down regularly due to natural disasters, sudden events like OPEC price hikes, etc) then the monthly inflation rate was zero and the annualised rate over the last six months is 2.5 per cent – which is in the middle of the RBA’s inflation targetting range.

3. If we take the annualised rate of that series, over the last three months, then the inflation rate is 2 per cent, at the bottom of the RBA’s range.

5. The rent inflation is partly due to the RBA’s own rate hikes as landlords in a tight housing market just pass on the higher borrowing costs – so the so-called inflation-fighting rate hikes are actually driving inflation.

6. Insurance inflation reflects the impact of several natural disasters (floods, fires, etc) – which are ephemeral events. This component is also being driven by the non-competitive banking sector gouging profits.

7. The general conclusion is that the global factors that were responsible for the inflation pressures are abating fairly quickly as the world adapts to Covid, Ukraine and OPEC profit gouging.

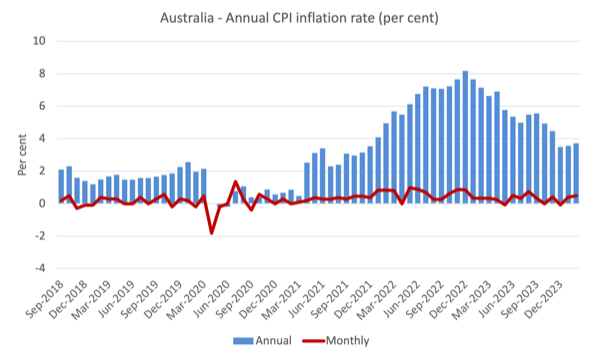

The next graph shows, the annual rate of inflation is heading in one direction – down with month-to-month variations reflecting special events or adjustments (such as, seasonal natural disasters, annual indexing arrangements etc).

The blue columns show the annual rate while the red line shows the month-to-month movements in the All Items CPI.

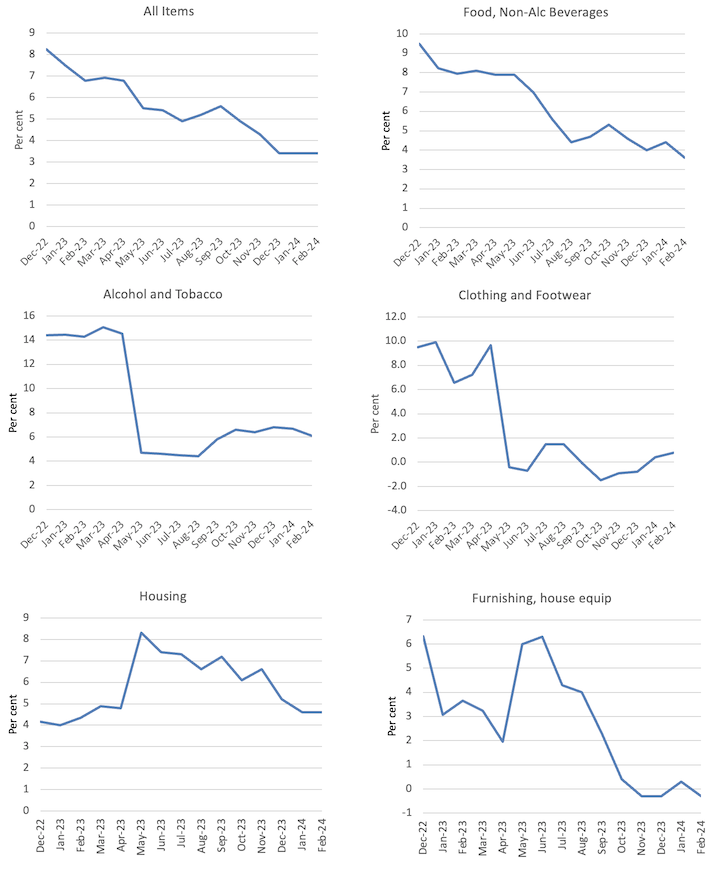

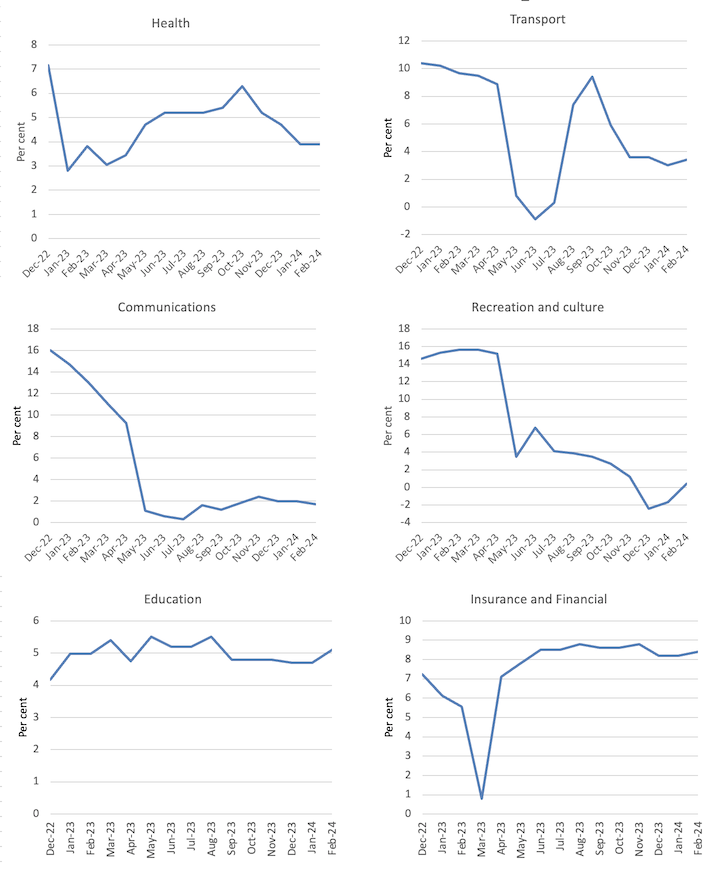

The next graphs show the movements between January 2022 and February 2024 for the main components of the All Items CPI.

In general, most components are seeing dramatic reductions in price rises as noted above and the exceptions do not provide the RBA with any justification for further interest rate rises.

For example, the Recreation and Culture component that was driving inflation in 2023 is now deflating – this just reflected the temporary bounceback of travel and related activities after the extensive lockdowns and other restrictions in the early years of the Pandemic.

It was always going to adjust back to more usual behaviour.

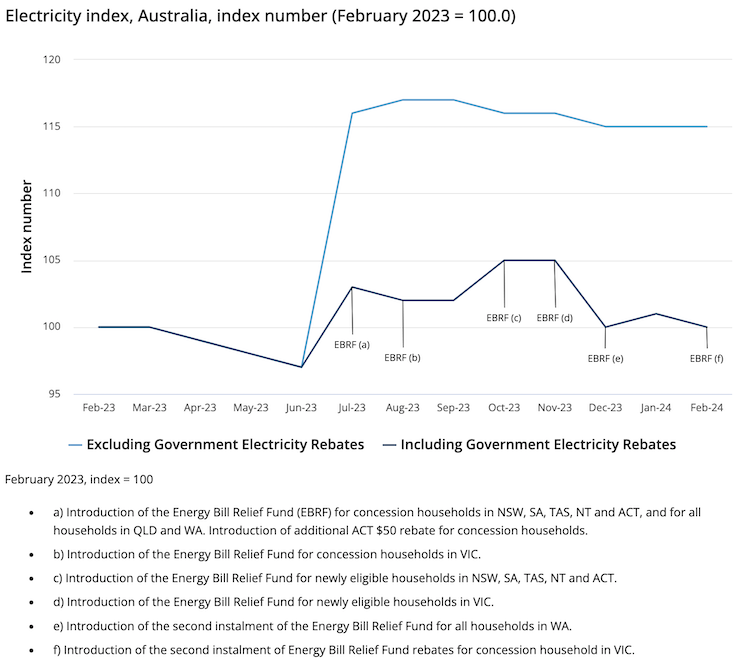

The ABS also published an interesting graph, which compares the electricity prices under the Federal government’s – Energy Bill Relief Fund – rebates which were introduced in July 2023 and what they would have been in the absence of that fiscal intervention.

The Relief Fund provided subsidies to households and small businesses depending on the locality.

For example, a Victorian household was given a rebate of $250.

The ABS report that without the rebates “Electricity prices would have increased 14.9% in the 12 months to February 2024”.

Here is the impact of that simple and very modest scheme.

It demonstrates that targetted fiscal policy can indeed be anti-inflationary, which means that the spending-inflation nexus is never straightforward as the mainstream narratives might have you believe.

The problem though is that the impact of fiscal policy overall has been negative over the last few years.

There has been a major slowdown in GDP growth and the declining retail sales figures as fiscal policy has shifted from producing deficits to surpluses over the last 12 months.

The mainstream perspective is that it has been the interest rate hikes that have caused the slowdown.

But during the GFC, the Australian Treasury conducted research to estimate the relative contributions of monetary and fiscal policy to the modest recovery in GDP after the massive global financial shock that we imported.

In the first four quarters of the GFC (January-quarter on), they estimated that the fiscal stimulus had contributed significantly to the quarterly growth rate.

On January 8, 2009 the Federal Treasury made a presentation entitled – The Return of Fiscal Policy – to the Australian Business Economists Annual Forecasting Conference 2009.

I wrote about that in this blog post – Lesson for today: the public sector saved us (January 21, 2009).

The other interesting part of their work was the estimates of the impact of the rapid reduction in interest rates by the Reserve Bank on GDP growth rates

This analysis provided a direct comparison between expansionary fiscal policy and loosening of monetary policy.

The conclusion was clear:

… this fall in real borrowing rates would have contributed less than 1 per cent to GDP growth over the year to the September quarter 2009, compared with the estimated contribution from the discretionary fiscal packages of about 2.4 per cent over the same period.

So discretionary fiscal policy changes was estimated to be around 2.4 times more effective than monetary policy changes (which were of record proportions).

While interest rates have been hiked 11 times since May 2022, the fiscal balance has shifted from a deficit of 6.4 per cent of GDP in 2020-21 and a deficit of 1.4 per cent of GDP in 2021-22, to a surplus of 0.9 per cent of GDP in 2022-23.

The Federal government is projecting another surplus in the current financial year.

That is a major fiscal shift and the fiscal drag explains most of the slowdown in growth and expenditure.

One commentator wrote today – Can Australia pull off the once-impossible with jobs and inflation? – that it was puzzling economists that with the rising interest rates, unemployment remained low.

There is no real surprise in this once we take into account two factors:

1. The recent inflation episode was not driven as the central bankers have claimed (excluding Japan) by excessive demand forces (over-spending).

It was a special event and the factors that drove the acceleration in the price level were of a supply-side origin and largely invariant to interest rate hikes, which made the whole response by central banks ridiculous and unnecessary.

The inflation was always going to fall.

2. But the rate hikes have had a demand effect, which relates to the asymmetry of monetary policy – a characteristic that central bankers do not want to talk about.

This asymmetry relates to the spending propensities of the different income groups that are affected by interest rate changes.

High income groups have lower marginal propensities to consume (meaning they save more per extra dollar of disposable income) than low income households.

They also have more financial wealth.

When interest rates rise, total spending by low income households doesn’t change much because they are already spending all their income.

Only the composition changes.

They also own very little financial wealth so do not get any income boosts via the rising returns.

For high income households, they gain a massive boost in income from their financial assets and even though they save more than low income households, their spending increases somewhat via the wealth effect.

These changes do not operate in reverse.

So where financial wealth is greater – for example, the US – and the fiscal policy is less restrictive, we are observing continued economic growth and low unemployment AND inflation falling.

The reason why the Phillips curve trade-off is not operating (falling inflation is not being accompanied by rising unemployment) is because the inflation was a supply-side rather than a demand-side event.

Most central bankers and economists got this very wrong.

So, it is much more likely that slowdown in GDP in Australia is the result of the fiscal drag rather than the interest rate increases, given the wealth effects of those with financial assets is likely to be lower in Australia than, say, in the US.

Music – When Did You Leave Heaven

This is what I have been listening to while working this morning.

I was looking through cupboards the other day where I have lots of old LPs stored and came across and old record from the 1950s by US guitarist and singer – Big Bill Broonzy.

He was one of the best guitarist-singers in the blues tradition and inspired many who followed him.

The song – ‘When Did You Leave Heaven’ – was recorded in 1936 as part of the movie – Sing, Baby, Sing.

It has been covered many times since.

This version came from a live concert recorded in Antwerp, Belgium in 1956.

Apart from the great singing and playing, the video is a work of art.

He died within 2 years of this concert from throat cancer (notice his smoking at the end!).

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2024 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.