In April 2023, the then governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia gave a speech to the National Press Club in Sydney – Monetary Policy, Demand and Supply = the day after the RBA decided to end (for a month) its rate hikes after hiking the previous 10 meetings of the RBA Board, the determine monetary policy settings. The inflation rate had been falling for some months by this time yet the RBA was still hanging on to its narratives that the rate hikes were necessary to “combat the highest rate of inflation experienced in Australia in more than 30 years”, despite, for example, the Bank of Japan holding rates constant and experiencing a more rapid decline in its inflation rate as the supply constraints abated. The RBA had vehemently claimed that wage pressures were mounting, which had to be curtailed and denied categorically that there was any profit gouging or margin push involved in the inflationary pressures. There was no evidence at the time to support their claims about wages and nominal wages growth has remained moderate since. However, there was ample evidence, both in Australia and across the globe that corporations were taking advantage of the supply constraints to push their profit margins out. A recent report released by Oxfam Australia report (June 19, 2024) – Cashing in on Crisis – demonstrates that profit and price gouging was instrumental in creating and sustaining the inflationary pressures. The RBA was in denial all along and demonstrated that they are essentially just part of the ideological machinery supporting neoliberalism and the extraction of greater profits at the expense of workers.

During his April 2023 Speech, the then RBA boss claimed that:

In terms of price-setting, the experience differs across firms and industries. However, at the aggregate level, the share of profits in national income – excluding the resources sector, where prices are set in global markets – has not changed very much over recent times … A reasonable interpretation of this is that, while firms on average have been able to pass on higher costs and maintain profit margins, inflation has not been driven by ever-widening profit margins.

Over the last few years, the RBA has been running a concerted campaign to push workers out of their jobs (aiming to increase unemployment by about 150,000) based on their claim that the unemployment rate was below the NAIRU = even though at various times they denied that they could actually estimate a specific NAIRU.

They think that if they push rates up far enough then total spending will crash and workers will be sacked.

They mask that by claiming they just want to fight inflation but they have been tripping up continually as they disguise their agenda with nonsensical statements about the NAIRU (for example, in June 2023) and the lack of a NAIRU (for example, in November 2023).

The fact is that their rate hikes have done little to suppress inflation which was falling rapidly anyway because its sources were in decline.

But the persistence of the inflation, which the RBA claimed was due to wage pressures has been more to do with profit push than anything.

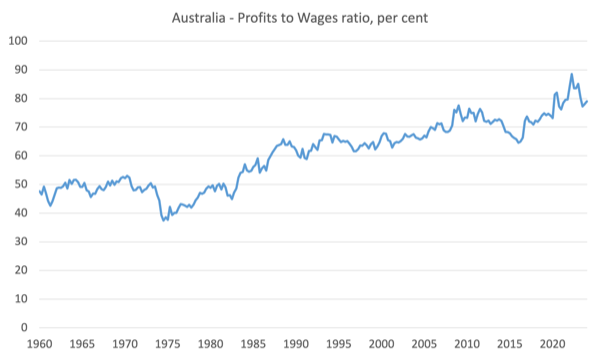

The following graph is calculated from the National Accounts National Income data and show the ratio of gross profits to the compensation paid to employees from the March-quarter 1960 to the March-quarter 2024, expressed as a percentage.

Prior to the neoliberal era that ratio was steady at around 50 per cent.

But since the mid-1975, when the federal government abandoned its comitment to maintaining full employment, the ratio has steadily risen and reached a peak of 88.5 per cent in the June-quarter 2022.

In the period, coinciding with the inflation build up – effectively from the June-quarter 2021 to the December-quarter 2022 – the profit-to-wages ratio was mostly rising and sharply.

The inflation started to abate not long after the profit-to-wage ratio peaked and then fell.

From the March-quarter 2001, up to the inflation peak, nominal wage payments grew by 15.8 per cent (over 7 quarters), whereas over the same period, gross profits rose by 27 per cent.

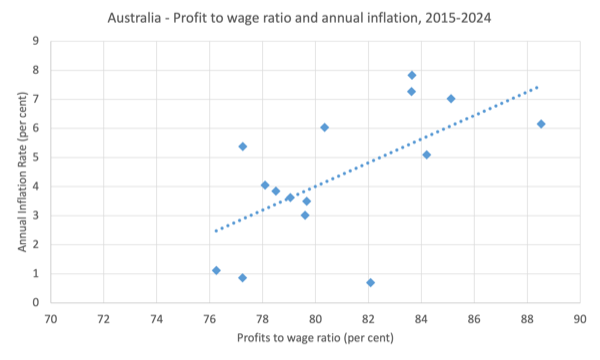

The next graph shows the relationship between the profit-to-wage ratio (horizontal axis) and the annual CPI inflation rate (vertical axis) since the March-quarter 2020.

The dotted line is a simple linear regression (which in statistical terms is very significant and tells us that for every 1 point rise in the profit-to-wage ratio, the inflation rate rises by about 0.4 points).

A caution though: further analysis is always required before the direction of the effect shown in cross plots is understood.

But the supporting evidence would suggest that profits push was an important driver of the inflationary pressures.

Today, responding to political pressure that it is letting the corporate world party at the expense of the rest of us, the Federal government announced that was imposing a mandatory behaviour code on supermarkets, which is a highly concentrated sector in Australia.

The current move is aiming to stop the oligopolist retailers from squeezing their suppliers so that the supermarket owners can make higher profits.

There are many examples now of how supermarket chains have punished wholesale suppliers who reject the demands for price and quantity from the retailers.

There is also an inquiry being done on consumer pricing by the supermarkets, which will report later in the year and the government has now commenced a price monitoring process to further put pressure on the supermarket chains.

All of these changes are minimal and will do little to change the profit-gouging mentality that is rife in Australian corporations.

Just how much profiteering has been going on was revealed in an Oxfam Australia report released last week (June 19, 2024) – Cashing in on Crisis.

The findings of the Oxfam report demonstrates that profit and price gouging was instrumental in creating and sustaining the inflationary pressures.

The Oxfam Report did what the previous RBA governor should have done in better detail:

… compared the 2021-2022 and 2022-2023 net profits of the top 500 Australian corporations with their average profits made between 2017-2018 and 2020-2021.

And they found:

… they raked in $98 billion in additional windfall profits, or ‘crisis profits’, that they wouldn’t have made under normal circumstances. Oxfam believes making billions during and off-the-back of overlapping crises is corporate profiteering. These profits are part of a wider crisis-fuelled inequality story, where billionaires were able to increase their wealth and boost their bank balances while the rest of us endured rising costs of living.

Pretty much the opposite of the story the RBA has been feeding the Australian public as it tried to lay the blame for the persistent inflation on wage earners.

The profiteering was most concentrated in the “mining, finance and supermarket and grocery sectors”.

The profiteering has also seen national income redistributed to the rich at the expense of the lower-income housholds, which means that income and wealth inequality has risen.

Oxfam summarise this in more lurid terms at the global level:

At current rates, we could have our first trillionaire in 10 years, yet we’re 230 years away from eliminating poverty.

And for Australia:

In 2022-2023, the richest 10% of households held 44% of all wealth in Australia, while Australian billionaires have done particularly well of late, increasing their wealth by 70.5%, or $120 billion since 2020.1

Unfortunately, the Oxfam analysis gets caught up in their belief that taxes on the rich will “boost the budget when crisis hits” and as a result some of the validity of the analysis is lost.

Tying action on profit gouging with helping to deal with the “stretched” government “budget” is promoting the sort of narratives that have allowed the corporations to escape an effective regulatory structure.

We read stupid claims that by introducing a “crisis tax”:

This revenue could have contributed to the cost of responding to the twin crises of the early 2020s and alleviating poverty It could have paid for the $47.9 billion in increased costs to the healthcare system from COVID-19, the $20 billion coronavirus supplement to income support (which lifted three million people out of poverty),19 and the $3 billion in energy bill relief. It also could have doubled our aid budget to around $9.8 billion for two years, and still left $7 billion for much-needed investment in social housing.

All of which could have been achieved simply through the existing fiscal capacity of the federal government.

If the real resources were available to accomplish these goals then no additional taxes would have been necessary.

I agree with Oxfam that the:

The system is broken and requires urgent attention to address the growing inequality. In addition to sorely needed reform of corporate competition laws, a tax on the crisis profits of corporations would be a disincentive to price gouging …

That is justification enough for action.

They should leave the ‘fix the budget’ stuff out of it.

While taxing these corporations would reduce their political power (lobbying etc) it would also have the additional advantage of maintaining lower inflation rates and undermine the central bank’s rate hiking obsession, which, by its own, has redistributed national income to the wealthy.

Think about that.

The causality runs like this:

1. Corporations with too much market power gouge profits in the crisis.

2. The CPI increases.

3. The central bank hikes rates, which redistributes national income from low-income mortgage holders to high-income and/or wealth holders of financial assets.

4. Profits rise even further (especially the banks).

That is the system in place at present and it represents the anathema of anything that a person concerned with social justice and fairness would come up with.

Conclusion

The overall conclusion from Oxfam is valid though:

Between the COVID-19 pandemic and high inflation caused by war and corporate profiteering, it was a tough start to the decade for most. Even in relatively wealthy countries like Australia, millions of people have been pushed to the brink by rising prices of food, energy and unaffordable rent. In stark contrast, this has been a profits bonanza for some of Australia’s biggest corporations.

We are a long way from fixing that mess.

The journey has to start with progressive organisations such as Oxfam rejecting the mainstream macroeconomic narratives about the government being a household with financial constraints.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2024 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.