In our new book – Modern Monetary Theory: Bill and Warren’s Excellent Adventure – which will be launched in the UK next Wednesday, we devote a chapter to what we refer to as the Japanese irony. This relates to the fact that while the conduct of policy in Japan is justified in mainstream terms, the more extreme policy settings that emerge produce outcomes that expose the deficiencies of the mainstream theories. At present, we are observing more examples of this. The latest matter of interest in Japan (from my watch) is the pressure the three megabanks are putting on the Bank of Japan policy makers to push up bond yields and interest rates. There is no reason based in financial stability concerns or community well-being for the Bank of Japan to agree to their demands. They just amount to special pleading from Japan’s fossil fuel financing megabanks for more corporate welfare to boost their profits.

The Irony of it All

While the Bank of Japan’s monetary policy stance and the fiscal strategies of the Ministry of Finance produced outcomes that demonstrated that the mainstream macroeconomic theory was inapplicable to a fiat monetary system, one should not assume that the Bank of Japan or the Finance Ministry ever abandoned orthodox ‘Monetarist’ thinking with respect to the causes of inflation and the role that interest rate increases might play.

The irony of it all lies in the stated reasons for their ongoing zero-rate monetary policy and their regular discourse surrounding the need for sales tax increases to ‘repair the budget’.

The Bank of Japan has made it clear that they feared a return to deflation and therefore kept rates low to sustain what they professed to be ‘expansionary monetary policy’.

And, as inflation has come down, they have celebrated the fact that they have been correct, and that the zero-rate policy to prevent deflation prevention was indeed the right course.

In that regard, their thought process remains the same as their fellow central bankers around the globe.

In March 2024, the Bank of Japan started pushing rates up a fraction, not because the financial markets were pressuring them to hike, but because they think, that now that they have probably escaped the deflationary bias, interest rate changes have an ongoing role to play in containing inflationary pressures that arise from demand-side pressures that stronger wage movements will bring.

That is a very orthodox view.

The irony, then, is that Japan’s pursuit of orthodoxy as they see it, unwittingly provides the perfect laboratory for validating MMT perspectives.

And the megabank want more corporate welfare from the Bank of Japan

There was an article in yesterday’s Japanese Times (July 10, 2024) – Japan’s megabanks are said to seek deep cuts to BOJ bond buying – which amounted to a special pleading by the profit-seeking banks for some corporate welfare, not that the mainstream media is able to see it in that way.

As an aside, these so-called megabanks are – Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group (MUFG), Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group (SMBC Group), and Mizuho Financial Group (Mizuho) – are known for their large-scale investments in carbon (fossil) fuel corporations.

This analysis of the role played by the international banks in maintaining the fossil fuel industry – Banking on Climate Chaos: Fossil Fuel Finance Report 2024 – published by the Rainforest Action Group with a host of partners, highlights the role the banking sector plays in putting profits before the well-being of society and the planet.

Just below JPMorgan Chase as the “worst financier of fossil fuels”:

Mizuho ranks #2 for financing overall. Mizuho increased its financing commitments for all fossil fuels between 2022 and 2023 from $35.4 billion to $37 billion. Mizuho rose 4 places in the overall annual ranks, from 6th in 2022 … Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group (MUFG) ($15.4B) ranks third worst among financiers of fossil expansion companies last year … Mizuho and MUFG, two of the three big Japanese banks, dominate the methane import/export (LNG) finance tables, providing $10.9 billion and $8.4 billion to companies expanding in the sector, respectively.

Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group (SMBC Group) was ranked 9th in the 2023 rating.

And the trend is for more financial commitments despite the mealy mouth press corporate speak we hear from the banks about their green credentials.

The Report found that:

While 33 banks decreased their financing for companies with fossil fuel exposure from 2022 to 2023, notably, 27 banks bucked that trend and increased their fossil finance commitments in that period. Among these include top ranking JPMorgan Chase, Mizuho, Morgan Stanley, Barclays, Goldman Sachs, and ING Group.

These Japanese megabanks are among the largest fossil fuel financiers since the Paris Agreement was finalised (2016-2023).

Further, the three big banks have targetted record earnings in the 2024-25 financial year on the back of anticipated higher interest rates, partly due to their belief that the Bank of Japan will steadily back away from its long-term zero interest rate policy and large quantitative easing purchasing programs.

The boss of MUFG told the press in May when it published its latest accounts that (Source):

We are now in a world of positive rates … so our interest margin will be improving.

He was stating the obvious that when interest rates rise the net interest margin on lending rates and borrowing costs increases.

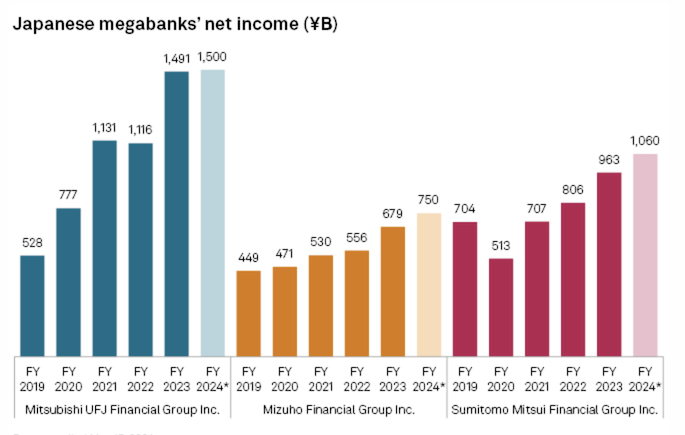

One should add that the big three produced massive increases in net income since 2019 even with the negative interest rate policy of the Bank of Japan.

This graph was compiled from the company statement in May 2024.

The big three dominate the domestic scene and recent Tokyo Shōkō Research study (Source):

… of 1,568,602 companies across Japan found that 125,942, or 8.03%, had MUFG as their main bank. This is the eleventh consecutive year for the bank to rank first in the survey, which was first conducted in 2013. The second-ranked bank was SMBC, which was the main bank for 99,225 or 6.33% of the companies, followed by Mizuho at 80,424 or 5.13%.

They reached this position as a result of several mergers and buyouts starting in the 1990s after the major property collapse in the early 1990s.

They are not only pivotal in influencing the viability of many Japanese corporations but their dominance also makes policy makers sensitive to their demands.

And there self-interest is going gangbusters at present as they have ramped up the pressure on the Bank of Japan to significantly curtail their bond buying program.

The Bank of Japan conducts regular meetings with the so-called ‘Bond Market Group’, which comprises representatives from the commercial banks, securities firms and the ‘buy side’ institutions.

The last meetings (the twentieth round) were held over July 9-10, 2024 and the head office of the Bank of Japan.

The Minutes for that round are not yet available, but the – Minutes of the 19th Round of the “Bond Market Group” Meetings (held June 4-5) – tell us that the commercial banks are expecting a “future rate hike by the Bank”.

It also states that:

Interest rates in Japan have become more likely to rise compared to overseas interest rates since the reduction in the Bank’s purchase amount of JGBs in a regular operation in May. With the Bank’s stance on the future conduct of its JGB purchases not being clear enough, the lowered predictability of the Bank’s market operations, which has resulted in the increased term premium, could have caused the rise in interest rates.

The participants were also concerned about the degree of liquidity in the JGB market with “the level of liquidity remains low due to continued large-scale JGB purchases and the stock effects of the previous purchases by the Bank.”

They told the Bank of Japan that the “market depth is insufficient” – which means they cannot get their hands on enough JGBS – because of “the effects of the Bank’s JGB purchases” – which means the Bank of Japan has been buying up much of the debt outstanding.

The Group also demanded that the:

… the Bank to proceed with the reduction in its purchase amount of JGBs in a stepwise manner.

While stepwise hints at gradual, the reality is that “One megabank said the BOJ should move early to make sharp cuts to its bond buying”, while another “megabank said the buying should be halved from the current monthly level to ¥3 trillion”.

The official word from the Bank of Japan is summarised in this document – Schedule of Outright Purchases of Japanese Government Bonds (Competitive Auction Method) (July 2024) – released June 28, 2024.

However, in its – Statement on Monetary Policy – released June 14, 2024, the Bank noted “that it would reduce its purchase amount of JGBs thereafter to ensure that long-term interest rates would be formed more freely in financial markets.”

So nothing definite.

But the so-called “whale in the pond of Japanese government bonds (JGBs)” which “pushed other buyers out of the water during an aggressive quantitative easing program” is clearly going to reduce its bond-buying exercise although given its massive holdings (its QE program “scooped up more than half of Japan’s outstanding government bonds”) the sell-off will have to be very gradual indeed or else financial disruption may be the outcome.

While the megabanks throw all sorts of justifications into the fray – such as if the Bank stops buying JGBs, the exchange rate will stop falling (because the yields and associated interest rates will rise) as capital inflow increases – the reality is this: they want higher income to flow from government via their own JGB holdings and higher interest rates to increase their net margins.

The more the Bank of Japan complies with their ‘timetable’ to run down the purchases the better the commercial banks will be.

This is just a special pleading case dressed up as a liquidity argument.

The point is that the commercial banks also want to JGBs to be issued and available in the secondary market because they know they are risk free and provide a benchmark upon which their other speculative products can be priced.

They also want a safe haven to run to in times of uncertainty.

There is no reason based in financial stability or community well-being for the Bank of Japan to agree to their demands.

The Japan Times article also claims that:

The BOJ’s plans are highly significant for the Finance Ministry. The retreat of the BOJ as the main buyer in the market has implications for yields that could push up the servicing costs of Japan’s massive national debt. It will also likely require a rethink of its own bond issuance management.

Which is not exactly correct.

It is true that the decision by the Bank of Japan will also impact on the Ministry of Finance because if bond yields rise, the interest servicing cost of the new issues will increase.

But all existing JGBs (except for the Floating-Rate bonds) will be unaffected.

As this Ministry of Finance briefing note – About JGBs – tells us:

The interest rate (nominal coupon rate) of a JGB is basically decided according to its market value on the day of the auction, and will remain unchanged till maturity.

Only the 15-year bond is issued as a floating-rate and are not an issue here.

The Government could, of course (and should) just stop issuing any new debt, which would shut this discussion down immediately.

Season 2 of our manga series – The Smith Family and its Adventures with Money – begins July 12, 2024

As I announced last Monday, the – MMTed – Manga series will return for Season 2 tomorrow, Friday, July 12, 2024.

There will be some new surprises, some turnarounds, crises, personal epiphanies, some loud music and more in Season 2.

In Season 1, we focused on the dynamics of the immediate Smith Family – Elizabeth, Ryan, Kevin and Emma – with some interaction from their friends.

In Season 2, the focus is on the school kids and their interactions with their new economics teacher Ms Allday.

Professor Raul Noitawl returns with his relentless analysis on the morning finance TV show but the real world events start testing the patience of his most loyal viewers.

Episode 1 begins with economic strife hitting the community.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2024 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.