This government has made some welcome announcements on housing but we can’t rely on private developers to build the homes we need

Yesterday, Angela Rayner announced the government’s intention to reinstate mandatory housing targets for local authorities to “get Britain building”, aligning with Labour’s campaign pledge to construct 1.5 million homes and deliver “the biggest increase in social and affordable housebuilding in generations.” Much of what was announced is encouraging with positive policies around enhanced flexibilities for social housing grants, reforming right to buy and prioritising social rent in line with NEF recommendations. Crucially, Rayner announced more grant funding for councils and housing associations will form part of the forthcoming spending review.

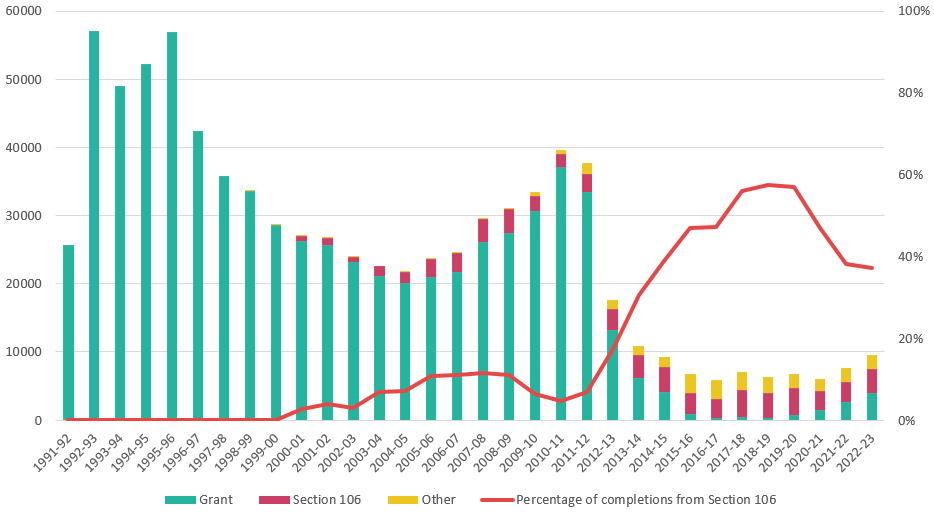

But ministers will need to make sure that the strategy delivers on their promises . The government has previously hinted towards a reliance on developer contributions through mechanisms like Section 106 (S106) agreements. Introduced in the 1990s, S106 are legally binding planning obligations requiring developers to contribute towards affordable housing and infrastructure as a condition of receiving planning permission. Over the past 15 years, S106 agreements have been crucial in delivering affordable and social housing, accounting for approximately 47% of all affordable homes built annually. However, S106 outputs have fallen far short of meeting housing needs and are unlikely to deliver the government’s ambitious targets on their own.

Figure 1: Social rent grant versus Section 106 completions since 1991

Source: Ministry for Housing, Communities and Local Government

Enforcement isn’t the only issue. S106 agreements tend to deliver more affordable housing in areas with high property values, exacerbating regional inequalities. For example, London alone received nearly 40% of all S106 contributions between 2013 and 2018, amounting to over £1.5 billion. Inequality is both regional and site-specific: there have been numerous instances of segregation within developments built under S106 agreements, to the extent that housing associations are reluctant to buy S106 homes due to their low quality. ‘Poor doors’ controversies, where affordable housing residents are given separate entrances and excluded from communal spaces, highlight the potential for these agreements to reinforce social divisions rather than create truly mixed communities.

Developer contributions alone are unlikely to meet the scale of social housing need. In the post-war decades, when local authorities were actively building homes, total housing completions often exceeded 300,000 per year. This period of high output coincided with substantial public investment in housing and fell when governments started to rely more on private development. The post-war New Towns programme, which created places like Basildon, Harlow, and Stevenage, was driven by public development corporations funded by Treasury loans. These corporations had extensive powers, including the ability to purchase land at existing-use value rather than inflated ‘hope value.’ This approach didn’t just deliver housing; it adequately addressed place-based housing needs and captured land value uplift for the public good. According to the Town and Country Planning Association, the £4.75 billion loan made to new town development corporations was fully repaid by 1999. Recent studies further strengthen the economic case for public investment in social housing; Shelter’s research found that building 90,000 social homes in one year would pay for itself within three years and return £51.2 billion to the economy.

To truly deliver on its ambitious housing goals, the government needs to commit to substantial public investment in social housing at the spending reviewWhile partnerships with private developers can play a role, the state must take the lead in funding and building homes to meet the scale of need.

This approach should include providing significant public grants to councils and housing associations for the direct building of social rent homes. Additionally, implementing land reforms to allow public bodies to acquire land at existing-use value will capture the planning uplift for public benefit. Strengthening planning powers is crucial, giving local authorities more robust tools to negotiate and enforce affordable housing contributions from private developers. Reforming Affordable Housing Programme (AHP) cost minimisation rules to prioritise social rent, with at least 80% of AHP grant money allocated to social rent and the remainder split between shared ownership and affordable rent, is essential. Furthermore, allowing social landlords to combine AHP grants with other grants and sources of capital, such as right to buy receipts, as announced yesterday by the housing secretary, will enhance their capacity to deliver the needed homes.

By combining public investment with reformed planning obligations and prioritising social rent, the government can create a robust, sustainable approach to delivering the social housing the country desperately needs. The package of investment to be outlined at the forthcoming spending review is vital to delivering the next generation of social homes the government has pledged to build. This strategy would enable us to build communities, tackle the homelessness crisis, and create a more stable and prosperous society for all.

Image: iStock