I. Bentham’s Bulldog

Blogger “Bentham’s Bulldog” recently wrote Shut Up About Slave Morality.

Nietzsche’s concept of “slave morality” (he writes) is just a dysphemism for the usual morality where you’re not bad and cruel. Right-wing edgelords use “rejection of slave morality” as a justification for badness and cruelty:

When people object to slave morality, they are just objecting to morality. They are objecting to the notion that you should care about others and doing the right thing, even when doing so doesn’t materially benefit you. Now, one can consistently object to those things, but it doesn’t make them any sort of Nostradamus. It makes them morally deficient, and also generally philosophically confused.

The tedious whinging about slave morality is just a way to pass off not caring about morality or taking moral arguments seriously as some sort of sophisticated and cynical myth-busting. But it’s not that in the slightest. No one is duped by slave morality, no one buys into it because of some sort of deep-seated ignorance. Those who follow it do so because of a combination of social pressure and a genuine desire to help out others. That is, in fact, not in any way weak but a noble impulse from which all good actions spring.

Some right-wingers have responded to the piece, but their responses are mostly “but I like being bad and cruel” – which seems to prove Bulldog’s point.

I think we can do better – that it’s possible to make a case against “slave morality” that doesn’t rely on being pro-badness and cruelty. I’m an expert on Nietzsche (I’ve read some of his books), but not a world-leading expert (I didn’t understand them). So take all of this as a riff on the concept, rather than a guide to Nietzsche’s original intent.

II. Friedrich Nietzsche

In the beginning (says Nietzsche), the word “good” was synonymous with “noble” – ie the virtues that made the nobility better than the serfs they ruled. This was way back in the Bronze Age, so your model for a noble should be Achilles, Agamemnon, etc.

The excellent noble delights in being strong, healthy, and virile. He lives in a beautiful palace and wears shining golden armor. He may be cultured, sophisticated, or even brilliant. He’s great at everything he does, and harbors ambitions to become even greater, maybe conquer a kingdom or two. He’s powerful, skillful, and awe-inspiring. Life is good!

Value systems naturally flow from elite to commoners. But a commoner can’t do much with this kind of master morality besides conclude “yeah, I suck”. Commoners are poor, sickly, and live in mud huts. They’re unlikely to achieve many goals beyond “not die”, and they’ve probably had their spirits crushed. But “I suck” isn’t a psychologically stable proposition. So sometime around the Iron Age, the slaves started working on a morality of their own, one where they’re the good guys and the masters are the losers.

Slave morality says that the strong are tyrants, the rich are greedy, and the ambitious are puffed-up braggarts. The wisest man is he who admits he knows nothing; the strongest man is he who conquers his own desires; it is easier for a camel to pass through a needle and so on. God loves the humble, the salt of the earth. The worst thing you can do is try to pridefully rise above your fellows (cf. Tall Poppy Syndrome); the best thing you can do is to lessen yourself, through methods sacred (fasting, celibacy, self-flagellation) or mundane (giving to charity, serving your fellow man).

Nietzsche speculates that slave morality originated with the Jews (an especially downtrodden and persecuted race) but caught on after the rise of Christianity. Sometime around the fall of Rome it took the lead over master morality, and it’s been gaining ever since. As time goes on, slave morality will become more and more dominant, master morality will fade into a dimmer and dimmer memory, and at some point we’ll come to what he calls the Last Man – someone so completely poisoned by slave morality that he worships mediocrity, feels no emotion but envy, and refuses to ever do anything because doing things seems insufficiently humble.

As an alternative, Nietzsche proposed the Superman. This concept is confusing, everyone gets it wrong, and I will also get it wrong. Sometimes it sounds like the Superman is the guy who brings master morality back in style. Other times it sounds like he reconciles both systems, keeping the best parts of each. Still other times, it sounds like he transcends them entirely.

But (asks Bentham’s Bulldog) why do we need this guy? Isn’t slave morality, with its concern for charity, peace, and equality – simply correct? Isn’t master morality – with its barbarian warlords bragging about how their golden palaces make them better than peasants – just wrong?

I want to give two linked negative perspectives on slave morality before coming back to Nietzsche’s question of whether there’s something better than either option. First, slave morality as ensmallening. And second, slave morality as an attempt to avoid positive judgment.

III. Ozy Brennan

Master morality favors the big. People with more stuff – more virtues, skills, accomplishments, wealth and power – are better. In a master moralist society, each individual is challenged to embiggen herself. Those who fail are judged worse than those who succeed.

Slave morality favors the small. It doesn’t openly, in so many words, challenge the individual to ensmallen herself. It just arranges the incentives so that they have to.

Ozy Brennan has a self-help post, The Life Goals Of Dead People. It’s framed as mental health advice. Maybe you’re some sort of guilty/anxious doormat type person. Your goals are things like:

-

I don’t want to make anyone mad.

-

I don’t want to hurt anyone.

-

I want to take up less space.

-

I want to need fewer things.

-

I don’t want to fail.

-

I don’t want to break the rules.

-

I don’t want to offend anybody

-

I don’t want to have upsetting emotions.

-

I want to stop having feelings.

Ozy points out that dead people achieve these goals better than the living ever could. If your life goal is to be more like a dead person, that’s a red flag for being a guilty/anxious doormat who needs to gain some self-confidence.

They suggest replacing some of these with the sorts of goals where living people outperform corpses. For example:

-

I want to write a great novel.

-

I want to be a good parent to my kids.

-

I want to help people.

-

I want to get a raise.

-

I want to learn linear algebra.

-

I want to watch every superhero movie ever filmed.

Ozy is very nice and basically never gets compared to barbarian warlords. Still, this essay is a master morality manifesto. Slave morality is goals for dead people. Corpses aren’t greedy. They don’t oppress anyone. They never hurt people. They don’t stand out, or try to be better than anyone else, or express pride. Slave morality is about compulsively making yourself smaller, weaker, less distinctive, and less disruptive to anyone else – which makes corpses the acknowledged experts.

Compare Achilles (master morality) to some of the early Christian saints (slave morality). Achilles wants personal glory. He seeks personal glory by being the best – the strongest, the most handsome, the most skilled in warfare – and by doing great deeds of renown. He had the most beautiful armor, the hottest women, and the best soldiers. When Agamemnon offended him, he was willing to let all of Greece perish to piss him off and restore his honor.

The early Christian saints definitely didn’t want personal glory – if anyone had tried to glorify them, they would have said something very pious like “I am only a humble servant of God, it is He who should be glorified”. They’re remembered primarily for their excellence in ensmallening themselves. They would fast until they became living skeletons, take vows of silence, or brick themselves in a tiny cell and spend the rest of their lives there. They would wash the feet of lepers out of humility, wear sackcloth to make sure they didn’t get overly proud about their clothing, and whip themselves bloody if they caught themselves having desires. Other religions’ saints are even worse – the Buddhists would try to meditate themselves into nonexistence!

At least the saints had the excuse that they were ensmallening themselves so God could fill them up with His own glory. But if you ensmallen yourself, you’ll just end up anxious, miserable, and devoid of accomplishments.

And at least the saints were doing this because they genuinely believed in it. For Nietzsche, the essence of slave morality is the herd instinct – ie a distributed mob of people saying “you had better ensmallen yourself if you know what’s good for you” as a sort of sinister backscratcher club. An individual might ensmallen themselves because of personal fealty to slave morality. But more often they’re doing it lest they look like Tall Poppies – people who defect from an unspoken social consensus that everyone ensmallen themselves, and so earn the envy and hatred of their peers.

IV. Edward Teach

The other useful way to think about slave morality is as a package of ideas that lets people avoid positive judgment.

(by “positive judgment”, I mean judgment based on whether someone has accomplishments – as opposed to “negative judgment”, judgment based on whether someone has avoided causing harm)

This comes from the same place as the embiggening critique. If people can be judged on their accomplishments, then it seems like you should go out and get some accomplishments, ie embiggen yourself. If people can only be judged on their harms, it seems like you should try to avoid causing harm, ie ensmallen yourself. So another way to think about slave vs. master morality is as coefficients on the normal utilitarian equation, good = benefits – harms. Master moralists overweight the benefits term; slave moralists focus on the harms.

In a second, I’ll list some strategies for avoiding positive judgment, but first, a warning. All good defense mechanisms contain an element of truth. People deploy these strategies because they’re often true. I’m not saying that these are all false things people only believe for psychological reasons – just that if you notice someone who seems obsessed with them, deploying them far more often than the truth seems to warrant, maybe there’s something psychological going on.

-

You obsess over the idea that the system is rigged. This is an obsession rather than a delusion – the system may very well be rigged, but you care about it way too much. The more rigged the system is, the less you can judge anyone positively for succeeding in it.

-

You believe that all virtues are subjective, meaningless, and kind of a grift. Intelligence” is just a measure of how you do on IQ tests; “health” is fatphobic and ableist; “hard work” is a scam by Puritan Boomers to stigmatize non-neurotypical learners. Again, these are obsessions and not delusions – it’s certainly reasonable to question traditional metrics of success – but at some point it becomes an attempt to avoid judgment because all potential judgment standards are corrupt.

-

You interpret any attempt to talk about good things, pursue good things, or (God forbid) achieve good things as a bid for status, and pre-emptively try to cut it down. You spread rumors about anyone who seems better then you. If they make too much money, they’re a shady profiteer; if they’re too smart, they’re an IQ-obsessed r/IAmVerySmart techbro; if they’re too pretty, they’re a slut. Your goal is to unite all the envious people into a Tall Poppy Police who agree that successful people suck, to prevent anyone from potentially judging you as worse than them.

-

You do everything ironically. If you did something non-ironically – wrote a deep poem that laid your entire being bare, committed whole-heartedly to a political position you truly believed in – you would be opening yourself up for judgment. Instead, you communicate only by tentatively putting out little feelers, and then, the moment someone starts to frown, retracting them with a “Haha, trolled, I was only joking”. If anyone else does things non-ironically, you deride them as “pretentious” and “cringe”.

-

You replace the normal cost-benefit calculus with your own version that ignores benefits and obsesses over harms. Scientific geniuses, lofty reformers, great altruists – all of their actions probably hurt a couple of people along the way to revolutionizing society, so only people who have never done anything at all are truly pure. If everybody who has accomplished things is a bad person, then you win by default.

-

You become collectivist. You demand that every action be done only after getting unanimous non-hierarchical collective approval. If someone is allowed to act individually, their action might go well, and then they would seem better than you. Or someone might ask you why you weren’t doing any good individual actions. Therefore, anyone who acts individually should be tarred as an arrogant defector who refuses to cooperate and hates other people, and the collective should pass laws banning whatever they did.

-

You believe that people should be judged not by their actions, but by the purity of their ideas. Actions are difficult and your actions might be bad, so you definitely don’t want to be judged on those. But ideas are easy, and you can always believe that your ideas are the most pure of all. Also, anyone who acts in the world or achieves something probably is less than 100% slave moralist, so if you judge people based on who has the purest slave moralist ideas, you will always be better than anyone with accomplishments.

When I first read Nietzsche, my question was: why worry about the master/slave dichotomy? Sure, maybe this was the way moral codes first formed during the Bronze Age; who cares? You can love excellence and be altruistic. It doesn’t take some Superman to combine them – you can just take the good parts of each. Right?

I think Nietzsche would have two answers:

First, you don’t pick your moral commitments like foods at a buffet. You deploy them as psychological defense mechanisms. You deploy slave morality when life has beaten you down and you want to maintain some of dignity. You don’t choose which subparts to swallow; you get whichever bits are load-bearing in your personal dignity-maintenance project.

And second, you may not be interested in slave morality, but slave morality is interested in you. Master morality isn’t interested in you – the masters are out achieving things and conquering places, they’re not going to take time out of their day to turn missionary and “convert” you to master morality too. But slave moralists are obsessed with ideological purity and invested in cutting down anybody who’s less slave moralist than they are. Even if you find it easy to avoid yourself, you need to be prepared to live in a slave morality world.

V. Jason Crawford

Nietzsche’s original dichotomy was aimed at the individual level, where people with psychological drives compete with each other for status. It doesn’t naturally transfer to the idea of societies. There’s a sort of trivial transfer where you can imagine superpowers boasting of their prowess and tiny city-states claiming the geopolitical game is rigged, but that doesn’t seem interesting to me.

When I think of master/slave morality at the level of societies, I think of the slave moralist herd instinct to enforce their slave morality on everyone else. This will be a feature of all societies – you could argue it’s what society/civilization is – but some will have it more than others.

Jason Crawford, one of the pioneers of Progress Studies, writes about a sort of mid twentieth century vibe shift.

In the 19th and early 20th century, Western civilization was busy trying to embiggen itself. Some of this was literal. In America, we had Manifest Destiny, our God-given right to stretch from sea to sea (my sometimes-hometown of Berkeley was named after the guy who coined the slogan “westward the course of empire takes its way”). Europe had colonialism, the White Man’s Burden, and eventually lebensraum.

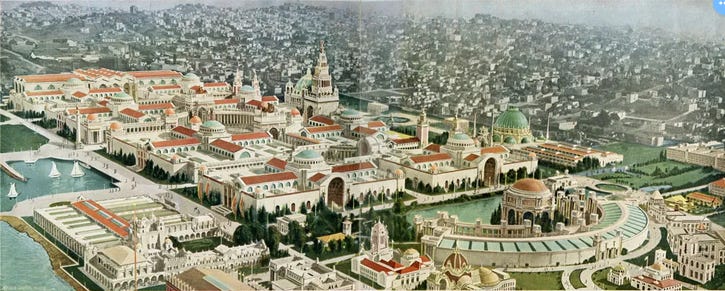

But some of the embiggening was metaphorical. We believed in the cult of progress. We would hold giant World Fairs, where we tiled whole cities with beautiful monuments called things like The Temple Of Machinery or The Altar Of Reason. They would have elaborate friezes of classical goddesses blessing railroads or holding sheaves of mechanically-reaped wheat. Inside, tens of thousands of men would come from every corner of the Earth to behold the newest inventions making our lives richer, safer, and easier. It seemed like we were heading for a Utopia of limitless plenty, and our only responsibility was to bring that great day forward as fast as possible and spread our greatness to as-yet-unenlightened corners of the world like Africa and Tibet.

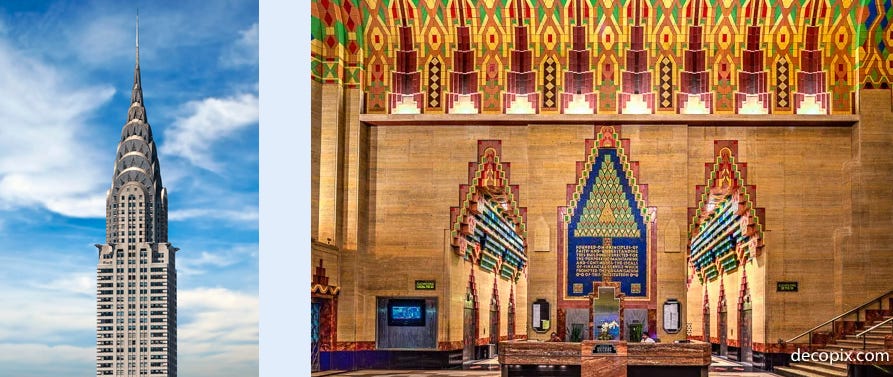

We erected glorious Art Deco skyscrapers, and boasted of how quickly they went up. We built the Empire State Building in a year and the Golden Gate Bridge in four. The interiors were bursting with color, ornament, and more classical goddesses representing Industry and Ingenuity or whatever. We held ticker tape parades for the glorious aviators and astronauts bringing us to ever-further corners of the world.

After (?) the trauma of the World Wars (?), something flipped. Instead of embiggening ourselves, we began to ensmallen. We replaced World’s Fairs with “World Expos”, which Wikipedia describes as “less focused on technology and aimed more at cultural themes and social progress”. Of the few inventions that did feature, more and more were “green tech” – machines aimed at reducing the damage we were doing to the world.

The classical goddesses got replaced by murals of ordinary workers, then abstractions, then nothing. The last ticker tape parade for an individual was 1998; since then the (relatively few, comparatively small) parades have all been for classes of people (NYC’s most recent was for “COVID-19 Essential Workers”).

Our buildings became smaller and duller. Last month’s Works In Progress magazine tried to investigate why. Some economists have blamed “Baumol’s cost disease” – as industrialization makes some things (like consumer goods) cheaper, other things (like skilled labor) become relatively more expensive. So maybe the rising cost of skilled labor put buildings like the one of the left out of reach. But Works In Progress found that wasn’t true; if anything, industrialization has made fancy buildings cheaper. They concluded that it was “a story of cultural choice, not of technological destiny” – in other words, people stopped wanting impressive buildings. The vibes were wrong, or something.

Intellectuals started feting ideas like degrowth. Degrowth says that it’s gross, greedy, and unsustainable to want economic progress. Instead, we should deliberately aim for economic regress, until First World GDPs are closer to those of South America or Africa. Advocates are careful to emphasize that as long as we take common-sense steps (like implementing socialism), this won’t force anyone to starve to death, just get rid of our useless luxuries – and in some sense, wouldn’t that make us better off?

The promised future utopia was replaced by almost unbroken dystopianism. Global warming will kill us all, or maybe we’ll be stuck in a cyberpunk world of hopeless soul-crushing inequality. Technological advance is interesting only insofar as it brings our cyberpunk hell closer and (unfairly) enriches some billionaires along the way. The only bright spots are occasional acts of voluntary ensmallening – power plants cancelled, products banned, indigenous tribes winning little legal triumphs over modernity.

Live-people goals like “build giant skyscrapers!” and “go to the moon!” could have been followed up with even greater live-people goals like “tile the desert with solar plants”, “create genetically-engineered superbabies”, “get one billion Americans”, or “cure all diseases”. Instead, they’ve been replaced by dead-people goals like “don’t damage the traditional character of communities” or “don’t damage the environment”.

Parts of this vibe shift still confuse me, but the zoomed-out version seems clear enough. The old pro-embiggening world was complicit in moral catastrophes – racism, colonialism, the Holocaust, the destruction of much of the natural world. At some point these atrocities caught up to and outpaced its very real accomplishments, and society stopped being proud of itself and shifted to a harm-reduction approach. Nobody comes out and says outright that harm reduction necessarily has to mean doing as little as possible and trying to make yourself smaller and less impressive and sadder and uglier until you curl up into a tiny point and disappear. But “slave morality” and “master morality” are attractors; if you select too hard for part of one, you end up with the whole package.

VI. Andrew Tate

I originally wanted to explain to Bentham’s Bulldog why slave morality wasn’t obviously “the good one” and master morality “the bad one”. Lest I come down too hard and get you thinking that master morality is obviously “the good one”, let’s talk about Andrew Tate.

In case you’ve been under a rock your whole life, Andrew Tate is a masculinity influencer. He’s a former world champion kickboxer who pivoted to self-help, sold scammy courses on business and relationships, and got rich. Some of his courses apparently recommended beating up women (I’m not sure if this was supposed to help your business or your relationship), and when people confronted him on this, his response was always “I’m strong and successful and own a Bugatti, which makes me better than you, you pathetic weakling failure”. He was credibly accused of rape (by “credibly” I mean that he sent one of the victims a text message saying “I love raping you”) and when people tried to cancel him over this, his response was always “I’m strong and successful and own a Bugatti, which makes me better than you, you pathetic weakling failure.” Finally he was indicted on one billion counts of sexual assault, human trafficking, and being a general scumbag of a human being; he is currently awaiting trial.

Tate has, in some sense, many good qualities. He’s strong, athletic, and motivated. He earned tens of millions of dollars through hustle and hard work. He’s charismatic and compelling and, before his arrest, was one of the Internet’s most iconic influencers. I think master morality has to approve of all these things.

Still, he’s obviously a jerk. This is exactly the situation that Nietzsche believes slave morality evolved for – letting me feel contempt for someone who’s stronger and richer and more successful than I am – and yup, now that I’m in this situation, I find myself definitely interested in a moral system that lets me do this.

The obvious compromise goes something like:

-

We can genuinely appreciate that Andrew Tate has the many good qualities listed above.

-

But also, his impulsive temper and fragile ego are bad qualities even by the standards of master morality.

-

And his violence, misogyny, and boastfulness are bad qualities by any morality with even the smallest consideration for altruism and common decency.

-

Therefore, we can feel contempt for him.

I don’t have anything better than this obvious compromise, but I’m not satisfied by it.

I would like to end up with an overall negative view of Tate. And if I do a simple calculation, (virtues – vices), then it seems like if his nonmoral virtues were strong enough, they could overcome the moral vices. If Tate was a really really good kickboxer, he might still end up in the black. It seems much more intuitive to say that no amount of nonmoral virtues can make up for his moral vices. But now we’re back at the full slave moralist package again! Some “compromise”!

Also, suppose Tate wasn’t a rapist, he was just some kickboxing champion who was a jerk to people online and constantly posted about he was better than them because of his Bugatti. I still want to feel contempt for him! Now we have to rate the vice of “boastfulness” so negatively that it overwhelms all possible positive virtues, which sounds like some kind of ridiculous straw man of slave morality.

All these problems would go away if we gave up on unified assessments of people. Then we could classify Tate as a very good kickboxer who also happens to rape a lot of people. But if we give up on unified assessments, aren’t we giving up on the very possibility of heroes? Isn’t this just the slave moralist denial of judgment?

Also, I think Nietzsche would say something something vitalism. He seemed to think there was a coherent conceptual unity between being strong, being skilled, and being some sort of unconstrained wild person who didn’t care what lesser people thought. Is there some sense in which Andrew Tate loses some genuinely valuable virtue, however small, if he becomes a normal civilized person who says please and thank you and is really respectful to everyone? Does he become less powerful, in some sense where powerfulness is good? Is he less able to achieve his destiny of being glorious? I’m genuinely unsure what Nietzsche would have thought of Tate, but it probably isn’t something as simple as “he should be nicer”.

I’m worried this still isn’t coming off strongly enough. You can argue “master morality is about being strong and good; slave morality is just about preserving your pathetic little feelings”. But most of life is people’s pathetic little feelings. People have proven over and over again that their decisions – about what to do, what to buy, who to vote for, even what to die for – depend more on what lets them feel dignity and self-respect than on any purely material considerations.

Every so often, usually on 4chan, you see an actual bully really going at it, unrestrained. Some kind of shock jock, saying “Note to unattached liberal women above 40: you are ugly hags who have lost your chance with men and all your eggs have dried up and nobody will ever value you anymore, you should either beg for some fat alcoholic guy to take you in since that’s the only man you can get, or resign yourself to being a cat lady growing old with nothing to do but dwell on your regrets and what could have been.” Outside of 4chan, there’s a sort of universal alliance against these people, which the rest of us join immediately and unconsciously. Is this the dreaded “herd” of “slave morality”? If so, long live the herd.

VII. Cotton Mather

Fine. Maybe we do need a Superman to sort this out. What are our options?

Preliminary question: where do the Puritans fall on this dichotomy?

On the one hand, they’re Christian, so they have a strong slave morality heritage. They talked a lot about humility, altruism, frugality, and self-discipline.

On the other, they sure did talk about them a lot. The Puritans were convinced that virtues were real and good. They were convinced that some people had more of them than others, and that made those people better.

The Puritans would have burnt you at the stake if you accused them of believing in the Promethean human spirit conquering the natural world. But they did sort of believe in it – at least enough to believe it was their moral mission to colonize a virgin continent.

My goal here isn’t to explore the weird Puritan theology around who was a good person (nobody, we are all incredibly sinful, but God chooses to redeem some people through no virtue of their own, and then those people are genuinely better off and do fewer sins). Rather, I want to examine two different forms (levels?) of slave morality.

In the first form, you replace the masters’ virtues with different virtues. But those virtues are still real. You can still embody them more or less well. This sort of creates a new hierarchy. The Puritans wouldn’t have respected a Bronze Age barbarian warlord. But they did respect the local minister. And the local minister was probably a smart, competent, disciplined, hard-working guy. From your respect for the local minister, you can rebuild civilization. Instead of obeying a warlord, you obey the minister, out of respect for the God and the values that he represents.

In the second form, you notice that the first form is just another hierarchy of masters. You (the wretched of the earth) used to be contemptible because you were weaker and poorer than the warlord. Now you’re contemptible because you’re less virtuous and disciplined than the minister. Even if there’s no local minister, everyone’s still keeping track of how you said the word “darn” once and are therefore unsuitable for God’s kingdom. So you decide to reject not just the masterly virtues (strength, wealth, etc), but also the slavish virtues (continence, dignity, altruism) in favor of . . . no virtues? The virtue of hating other virtues, which shows that you’re enlightened to the true nature of the world where all virtues are fake?

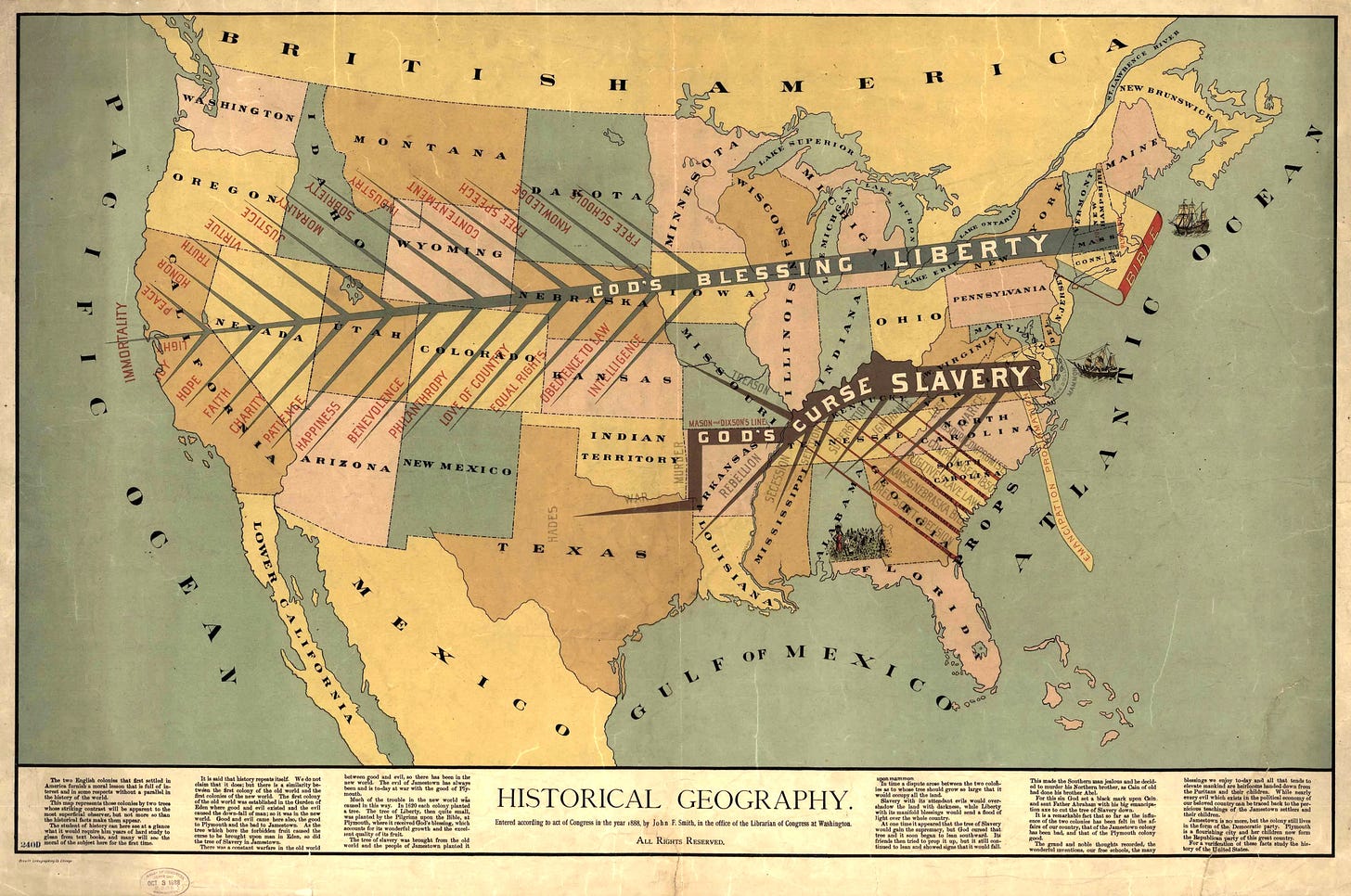

I used to have this map on my wall:

It’s Progressive-era propaganda about the superiority of the American North over the South, but I find it most interesting for its list of virtues. It starts with Liberty, then moves on to Free Speech, Intelligence, Obedience To Law, Knowledge, Equal Rights, Free Schools, Contentment, Love Of Country, Philanthropy, Benevolence, Happiness, Patience, Charity, Faith, Hope, Joy, Industry, Sobriety, Morality, Justice, Virtue, Truth, Honor, Peace, Light, and Immortality.

I appreciate the Progressive virtues because of how skew they are to most of the ethical systems I encounter. They’re not leftist (Love Of Country? Industry? Morality?) or rightist (Equal Rights? Free Schools?). They’re not Nietzschean master moralist (Philanthropy? Contentment? Benevolence?) or slave moralist (Industry? Knowledge? Honor?). They’re Christian-ish, but not hair-shirts-and-self-flagellation Christian or God-n-guns-megachurch Christian. They’re the kind of Christians who you can kind of tell are going to end up supporting eugenics in a few years.

I think I would classify them as a first-form-slave-morality liberalism, whereas most of the liberalism you encounter these days drifted at least a little into the second form.

I’m not 100% on Team Early 20th Century Progressive, but they give me hope that there are weird-yet-coherent groupings of virtues we haven’t even imagined.

I feel the same way about some old Soviet posters:

These are obviously left-wing, in the sense that they’re literal Communist propaganda. But to the modern eye there’s something off about them, something that makes you want to call them right-wing or even fascist. They’re bold and optimistic. Even though the commissars who commissioned them probably rejected some traditional or capitalist conception of virtue, they still firmly insist that there’s something sort of like virtue or power which is attainable and good.

I think these are first-form posters, and that most modern leftism is second-form. I think if you had to group barbarian warlords, Puritans, Soviet communists, and modern leftists on a Nietzschean/geneaological/aesthetic axis, it would go:

(Barbarian warlords) | (Puritans, Soviet communists) | (modern leftists)

So one very weak compromise – hardly even a compromise, since it predates Nietzsche – is to try to stick with first-form slave morality, in the hopes that most of the problems come from the second.

VIII. Ayn Rand

“Is Ayn Rand a Nietzschean?”- the greatest thread in the history of forums, locked by a moderator after 12239 pages of heated debate.

There’s a real answer here. Rand started out respecting, maybe even loving Nietzsche. She once said that:

[Nietzsche’s] Thus Spake Zarathustra is my Bible. I can never commit suicide while I have it.

…which maybe reveals more about her psychological situation than I expected from the answer to a “who’s your favorite philosopher” questionnaire. But later on she broke from him. It’s hard to figure out her exact position – she has a bad habit of treating anyone who disagrees with her in any tiny detail as the Antichrist, such that it’s hard to figure out whether she thinks of someone as a 99% fellow traveler or an arch-enemy.

Still, there are substantial differences. Nietzsche is more chaotic – he expects the superior man to defy all external rules in favor of his own glorious destiny. But Rand is attached to rules – most of all the epistemic rules of Reason, but also the usual moral tenets like “don’t kill” and “don’t steal”. Nietzsche’s masters take the Ron Swanson approach to justifying their actions:

…whereas Rand’s masters are prone to giving twenty-page-long arguments for why whatever they’re doing is the right choice according to Objectively Correct Moral Law.

Rand’s approach has lots of advantages. The Nietzschean master, like Andrew Tate, is an awful guy to have around. It’s hard to fit him into a functioning civilization, except maybe an autocracy with him as autocrat. Nietzsche’s pitch is “hey excellent people, you should try to become this guy”, never “hey normal people, you should support my project of creating these guys, out of your own self-interest.” The latter wouldn’t pass the laugh test.

Rand’s masters, while still probably very stressful to be around, have been tamed. They follow civilized rules of honesty and nonviolence – not, of course, because they’re too weak to defy them, but because following civilized rules is objectively the coolest thing of all. Instead of competing in battle and leaving a trail of bloody corpses, they compete in Capitalism and leave a trail of high-paying jobs and excellent consumer goods. They’re not doing to serve you – “I should serve the little guy” is slave moralist bulls**t. But, by coincidence, their excellent actions are doing you a service. They might only invent rocket ships to enact their Promethean conquest of nature and prove their own greatness. But you still get to ride in one.

Rand also spares more of a thought (or at least an afterthought) for the little guy. Capitalism needs all types – even the company janitor genuinely contributes to whatever glorious accomplishments are going on, and deserves to feel good about themselves. She wants everyone to be the best, most ambitious, and most fighting-for-their-own-aesthetic/moral-vision they can be. But if that means being the company janitor, that’s fine. And if you love rockets and you consummate that love by becoming the janitor for a rocket company, the Objectively Correct Moral Law is 100% on board. I am not a Nietzsche scholar, but I think this is a more productive answer than Nietzsche has for this question.

The disadvantage of Rand’s approach compared to Nietzsche’s is that it only works if you believe her proofs about why the Objectively Correct Moral Law is definitely objective and correct – most of which seem to me to be either hand-wavy or balderdash. Otherwise the whole thing breaks down – why is the most masterful thing to be a positive-sum capitalist instead of a negative-sum warlord? Rand really really wants to justify a peaceful, glorious, positive-sum society, to the exact people most capable of benefiting from defecting against it, without bringing in altruism or the common good at any point. It’s an extremely sympathetic goal. But I don’t think she makes it.

Still, this is why I’m fond of her. If you really read her books – as opposed to skimming them while subvocalizing “this is that evil woman who loves selfishness” under your breath the whole time – it’s obvious that she believes, with a deep and burning belief, that good things are good. She really really wants to think that you can objectively convince people to support a peaceful, glorious, positive-sum society, without any hint of the psychologically-toxic slave morality that typified the USSR she grew up in. When people react to her books with loathing – without even a hint of fondness – I get suspicious that they’ve gotten so deep into slave morality that thy can’t recognize goodness when it hits them over the head with a sledgehammer. Elsewhere, I wrote:

Edward Teach (Sadly, Porn) is famous for making up fake novels to criticize, and it is a little known fact that the “Ayn Rand” character along with all her novels are 100% his work. They operate as a diagnostic test based on his psychodynamic theory of envy.

The instrument presents a picture of some exceptional people achieving great things who don’t apologize for their greatness, and doesn’t explicitly ask the patient – I mean, reader – for their opinion.

If the reader has no strong opinion, or says something like “Good for them, I guess,” she passes the test. “I like these people and will use them as a role model” also passes. Some specific criticisms (see below) may also pass.

If the reader says “Ah, people who are better than the pathetic sheep around them, just like I’m better than all the pathetic sheep around me!”, she . . . still passes the test. That’s not what it’s testing for!

You fail the test if you absolutely freak out about some combination of the Rand characters themselves and the potential existence of arrogant people who identify with the Rand characters. The secret is that it’s not a screening test for the kind of people who would get featured on /r/iamverysmart. It’s a screening test for the kind of people who would comment on /r/iamverysmart, ie the self-designated Tall Poppy Police, ie the people who build their ego off being the enforcers of the rule that you’re not allowed to look better than anyone else.

These people’s basic mental stance is to hate people who seem too excellent. They don’t think of it in these terms. They think of it as calling out arrogance, although if you look too closely you’ll find their definition of arrogance covers anyone who seems excellent and but doesn’t spend all their time apologizing and abasing themselves and denying it. The brilliance of Teach-Rand is how he-she draws this tendency to the foreground

For example, why the whole “Objectivism” thing? Not because value is necessarily completely objective, but because the idea that any value might ever be even partially objective freaks out the Tall Poppy Syndrome people. Mention value at all, and they say you must be trying to secretly smuggle in the assumption that you are more valuable than other people (and therefore you are less valuable than other people, and therefore they are better than you).

The same is true of Reason. Mention that Reason exists, and they’ll interpret it as a claim that you, the only rational person, are claiming to always be right and infallible. But (they retort) actually nobody knows anything, and the only wise people are the people like them who humbly admit this.

(how do you decide what’s true without Reason? By bias-based-reasoning – “You say X, but I can imagine a way that would come from a place of believing you’re better than other people, therefore, Not-X is true. You say that’s a logical fallacy? That must come from a place of believing you’re smarter than everyone else and the only person who can use Facts and Logic.”)

The Teach-Rand test is designed to catch the sort of person who, if someone says that on a right triangle a^2 + b^2 = c^2, responds with “Oh, so you’re claiming to be some kind of right triangle expert who’s better than the rest of us? You really need to work on that arrogance problem! Super cringe!” Any criticism of the book that doesn’t come from this particular place is irrelevant to the test and doesn’t count against your grade.

(which is good, because the books are bad in a lot of ways. But that’s fine – Rorschach blots don’t also have to be great art!)

Still, I don’t think she’s the superman (superwoman?) who successfully transcends the dichotomy Her philosophy is only as strong as its proofs of Objective Correctness, which I consider weak. Without those, you need some subjective motivation to glue things together – of which altruism is the most popular.

But also, don’t we like altruism? When we’re bestriding the Earth like colossi, working on our glorious rocket ships to colonize the universe, isn’t part of what we’re thinking “this is going to revolutionize humankind and make everybody better off?” If you force yourself to reject that motivation, to just repeat “no no no, I’m only doing this because rockets are really big and make cool explosions”, aren’t you cutting out a part of yourself, in exactly the way Nietzschean masters are supposed to try to avoid doing?

I find something very compelling about Rand. I think she goes some of the way to answering the Andrew Tate objection to master morality. But she’s a means and not an end. A real superman would have to figure out some way to reintroduce basic human kindness.

IX. Matt Yglesias

Yglesias’s mantra – “good things are good” – is too perfect and profound to come from anyone other than an esoteric master of Nietzschean philosophy.

Nietzsche wrote in the 1890s. There were still real nobles and emperors walking around; communists had not yet started calling capitalism “late capitalism”. Sure, his world was probably some sort of weak compromise between master and slave morality, but it was different from our weak compromise. Our weak compromise was forged through dialogue and warfare with fascism’s novel take on master morality and socialism’s novel take on slave morality. I think of Yglesias – who combines an insistence that good things are good and a proclivity for embiggenment with commitments to democracy, the welfare state, and the poorest among us – as one of its most self-conscious proponents.

The compromise goes something like:

-

Everyone is equal before the law, before the metaphorical throne of metaphorical God, and in some poorly defined philosophical sense. This is very important. It’s our headline result. Everything else should be interpreted in light of this central fact.

-

That having been said, some people are obviously better at specific limited skills and virtues than others.

-

Most skills are partly genetic and partly environmental. We will grudgingly let scientists study this and publish their results, but everyone should play up the environmental component as much as the science allows, and awkwardly sidestep the genetic component, in order to defuse “innate superiority” claims.

-

If someone happens to end up unusually skilled or powerful, that’s fine, they deserve some limited respect, and they can keep their skills and power. In exchange, they should be humble, not claim any kind of fundamental superiority, and discourage hero worship. If they’re forced to draw attention to their advantages, they should talk about how they benefited from privilege, and how millions of people with the same skills are unfairly languishing in poverty.

-

The existence of rich people can be challenged, but can ultimately be defended on the grounds that they create jobs and valuable products for the masses. Rich people owe a debt to society for creating the conditions in which they can flourish; by coincidence, this debt exactly matches the current tax rate in their jurisdiction.

-

The value of technological progress, economic prosperity, and cultural sophistication can also be challenged, but can be similarly defended insofar as they improve the lot of the worst-off and improve equality. For example, GDP growth is good since it lifts people out of poverty; new discoveries about the nature of the brain are good since they might one day produce Alzheimers drugs; art is good since it can include underrepresented groups or teach some kind of lesson about social progress.

-

We should use checks, balances, vetocracy, and redistribution to limit the power of any individual to some ceiling, although people can disagree on how high the ceiling will be and right now it’s pretty high.

Slave morality hates power/excellence and refuses to justify it. Master morality says power/excellence is its own justification, and the rest of us have to justify ourselves to it. Liberalism says that sure, we can probably justify power/excellence, as long as it stays within reasonable bounds and doesn’t cause trouble.

Slave morality ignores benefits and sets the importance of harms at infinity. Master morality ignores harms, and sets the value of “benefits” (not that it would think of it in these terms – greatness doesn’t exist to benefit others) at infinity. Liberalism accepts the normal, finite utilitarian calculus and tries to balance benefits against harms.

A final secret of this compromise is that master morality and slave morality aren’t perfect opposites. Master morality wants to embiggen itself. Slave morality wants to feel secure that everyone agrees embiggening is bad. The compromise is that we all agree embiggening is bad, but leave people free to do it anyway. So half of Western intellectual output is criticisms of capitalism and neoliberalism, yet capitalism and neoliberalism remain hegemonic. Everybody agrees to hate billionaires; also, billionaires are richer than ever.

This isn’t a complete solution – sure, we’re a free country, but we’re also a democracy, and if people hate something too much they can ban it. But add in the utilitarian justifications above, and it sort of hangs together.

X. Richard Hanania

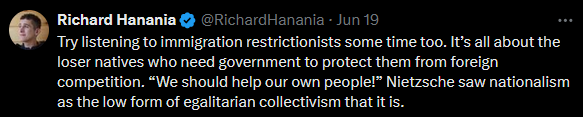

So liberal democracy is an uneasy compromise between slave and master morality. One natural interpretation is that the left is the party of slave morality, and the right of master morality. I appreciate how directly Richard Hanania proves that wrong.

Richard is an honest-to-goodness Nietzschean master moralist, one of the last you’ll find. Like Rand, he tries to combine Nietzschean master morality with a civilized society and obedience to law. Unlike Rand, he’s not obsessed with presenting a bunch of multi-step proofs showing exactly how it works, and honestly I’m not sure of the exact details. I find him interesting insofar as it clearly works inside his own head and he’s clearly coming from a place of aesthetic coherence. He writes:

We can call my philosophy Nietzschean Liberalism. The Nietzschean part consists of the following beliefs.

Just as intelligence, a moral sense, aesthetic appreciation, and other factors place humans above animals, some humans are in a very deep sense better than other humans.

Society disproportionately benefits from the scientific and artistic genius of a select few. An important goal of government and public policy is to channel their energies in productive directions and leave them free to pursue their missions.

As confirmed by modern behavioral genetics, heredity is the dominant force behind human variation.

Egalitarian ideology and concerns over what is called “social justice” are primarily driven by ugly instincts, namely envy and feelings of inferiority.

While all rational beings must be utilitarians to some degree, everyone has non-utilitarian commitments. The best ones put an emphasis on beauty, freedom, and progress, rather than pleasing supernatural beings, fealty to some “natural” order, the glorification of imagined communities like nations, or equality of outcomes.

So far so predictable. He haltingly endorses the liberal compromise as the best way to make it work:

Markets and democracy are the best forces ever discovered for pushing ahead with the creative destruction necessary for human progress.

Even extremely flawed or limited human beings can still have much to contribute to society due to the miracle of the division of labor. There is thankfully no need therefore to turn towards ideas that involve incapacitating or repressing large numbers of people, with the relatively few criminals among us being the exception.

Human nature is not so bad that collectivist and egalitarian ideologies are always going to be prevalent among the masses. They simply need to be protected from cancerous ideas that make them a threat to progress, which come from both the right and left. Somewhat paradoxically, democracy does a pretty good job of this relative to other systems.

Okay, so right-wing guy claims to be Nietzschean, why am I saying this disproves something about partisan politics?

Hanania is terrible at being right-wing. He’s pro-choice, pro-immigration, pro-euthanasia, pro-vaccine, pro-globalism, pro-Ukraine, atheist, and supports the recent guilty verdict on Trump. As with Donald Trump, he’s living proof that right-wingers will welcome anyone sufficiently offensive without caring about their policy positions.

My impression of Hanania is that his Nietzscheanism is incredibly deep, principled, and heartfelt, while his right-wing-ness is at best an alliance of convenience. This adequately explains most of his positions:

-

He’s pro-immigration because he’s obsessed with excellent/talented people and wants them to come to the US and use their talents more effectively.

-

He’s pro-vaccine because he appreciates the Promethean triumph of technology over the natural world.

-

He’s pro-euthanasia because he’s disgusted by the idea of sickness and weakness. It feels intuitively obvious to him that once you’re sick and weak there’s no point in living and you’d rather die.

-

He started out as pro-Russia because he thought Russia was stronger and more vigorous than the West. When Russia failed in its initial invasion, and Ukraine outperformed everyone’s expectations, Hanania flipped to Ukraine’s side, because he realized that Russia was incompetent, Ukraine was courageous, and the West’s cultural package made it more powerful and impressive than its autocratic competitors. Also, I’d expect he was disgusted by Putin’s policy of sidelining/arresting talented people in his government to prevent them from threatening his power, and was anxious to switch to the side that does less of that sort of thing.

Meanwhile, as Hanania has noticed, MAGA Republicans are slave moralists. They want the talented (high-skilled immigrants, economists, artists, intellectuals) to be permanently yoked to an underclass of obese conspiracy-theorist hillbillies. They’re raising tariffs to protect weak American companies from stronger foreign competitors, banning IVF and vat meat and any technology that makes them uncomfortable, and trying to retvrn to some kind of crunchy organic notion of life which probably doesn’t even have any skyscrapers. Even the right’s so-called Nietzschean vitalists are mostly LARPing steppe nomads instead of building rockets.

There is no Nietzschean political party. There isn’t even a properly Nietzschean subculture or coalition. It’s just Richard Hanania and a handful of his Substack followers.

XI. Sid Meier

I said above that the liberal compromise was utilitarian-flavored. Slave morality can grudgingly accommodate action, virtue, and exceptional behavior if these are justified as eventually being good for the weak. I also said that the liberal compromise involved a lot of saying stuff that nobody is expected to believe or follow.

I think effective altruism is what happens when you actually enthusiastically endorse this part of the compromise – the part you were supposed to grudgingly accept as an excuse for what you wanted to do anyway.

Certain flavors of the liberal compromise, accepted grudgingly and half-heartedly, are psychologically toxic. A common one says – go achieve whatever is considered normal for your class. Get a degree at Yale, go into finance, and get a brownstone in Brooklyn – as long as you very slightly hate yourself and think that in an ideal society you wouldn’t exist.

Effective altruists have all sorts of normal mental problems – depression, anxiety, what have you. But I’ve noticed they have much less of the sort of toxic self-hatred that comes from tying yourself in knots around this stuff.

I wouldn’t have noticed this if not for the movement’s enemies. Everyone naturally disagrees with their critics – but as someone who gets criticized from lots of different angles, the EA critics boggle me the most. Not the ones who think some other charity is more effective; those guys are fine. I mean the ones who totally ignore where the charity goes and vomit twenty pages of the words “arrogant”, “billionaire”, and “white”. The reasons these people hate effective altruism never seem to connect at all with the reasons I find it valuable.

My working model of these people’s psychology is something like: if you admit that charity is good, or that some charities are better than others, that’s an objective value. Any objective value lets you smuggle in the claim that some people are better than others. These people’s psychopolitics focus almost entirely on cutting down Tall Poppies, and on pre-emptively salting any soil that might one day allow a Tall Poppy to grow. An optimist might say this is because their first commitment is to the ultimate equality of humankind, beyond any commitment to short-term material welfare. A cynic might say they’re fallen so deep into Avoidance Of Judgment Hell that it’s impossible for them to parse any action or belief except as a hostile status claim – and that it’s impossible for them to treat the external world, whether starving people live or die, etc, as anything other than a prop in their internal status obfuscation pantomime. While a normal person might hear “Bill Gates led an amazing anti-malaria campaign that saved ten million people’s lives” and have some sort of emotion about the ten million lives being saved, these people only hear the word “led” and become obsessed with the need to cut Gates down a notch so people don’t think he’s cooler than they are.

But if you do a good enough job translating from Narcissist to English, these people aren’t completely wrong. Effective altruism tries to double down on the liberal compromise: it’s permissible to embiggen yourself (or your civilization) if say you’re doing it for the general welfare. This lets you add the missing altruism back into Rand. You can be an glorious-destiny-having billionaire, and instead of using your skill to pursue a vision of building a giant gold mansion, you can use your skill to pursue a vision of making the world a better place. Or you can be a scientific genius, and instead of transcending your fellows with arcane visions of the gears of the universe, you can work on curing malaria or something. I don’t think any of this matters as much as the external-world perspective where real people are helped in the real world. But as long as you’re helping people, I think it’s also permissible to use it to resolve seemingly-unsolvable deep questions about the narrative of your life.

I’m an expert on Nietzsche (I’ve read some of his books), but not a world-leading expert (I didn’t understand them). And one of the parts I didn’t understand was the psychological appeal of all this. So you’re Caesar, you’re an amazing general, and you totally wipe the floor with the Gauls. You’re a glorious military genius and will be celebrated forever in song. So . . . what? Is beating other people an end in itself? I don’t know, I guess this is how it works in sports. But I’ve never found sports too interesting either. Also, if you defeat the Gallic armies enough times, you might find yourself ruling Gaul and making decisions about its future. Don’t you need some kind of lodestar beyond “I really like beating people”? Doesn’t that have to be something about leaving the world a better place than you found it?

Admittedly altruism also has some of this same problem. Auden said that “God put us on Earth to help others; what the others are here for, I don’t know.” At some point altruism has to bottom out in something other than altruism. Otherwise it’s all a Ponzi scheme, just people saving meaningless lives for no reason until the last life is saved and it all collapses.

I have no real answer to this question – which, in case you missed it, is “what is the meaning of life?” But I do really enjoy playing Civilization IV. And the basic structure of Civilization IV is “you mine resources, so you can build units, so you can conquer territory, so you can mine more resources, so you can build more units, so you can conquer more territory”. There are sidequests that make it less obvious. And you can eventually win by completing the tech tree (he who has ears to hear, let him listen). But the basic structure is A → B → C → A → B → C. And it’s really fun! If there’s enough bright colors, shiny toys, razor-edge battles, and risk of failure, then the kind of ratchet-y-ness of it all, the spiral where you’re doing the same things but in a bigger way each time, turns into a virtuous repetition, repetitive only in the same sense as a poem, or a melody, or the cycle of generations.

The closest I can get to the meaning of life is one of these repetitive melodies. I want to be happy so I can be strong. I want to be strong so I can be helpful. I want to be helpful because it makes me happy.

I want to help other people in order to exalt and glorify civilization. I want to exalt and glorify civilization so it can make people happy. I want them to be happy so they can be strong. I want them to be strong so they can exalt and glorify civilization. I want to exalt and glorify civilization in order to help other people.

I want to create great art to make other people happy. I want them to be happy so they can be strong. I want them to be strong so they can exalt and glorify civilization. I want to exalt and glorify civilization so it can create more great art.

I want to have children so they can be happy. I want them to be happy so they can be strong. I want them to be strong so they can raise more children. I want them to raise more children so they can exalt and glorify civilization. I want to exalt and glorify civilization so it can help more people. I want to help people so they can have more children. I want them to have children so they can be happy.

Maybe at some point there’s a hidden offramp marked “TERMINAL VALUE”. But it will be many more cycles around the spiral before I find it, and the trip itself is pleasant enough.