It seems that since they were elected British Labour, principally the Leader and Chancellor, have thought it necessary to put out ever increasing messages of doom and the need for tough fiscal action – aka austerity – despite them claiming when they were wooing the electorate that they would not pursue that ‘Tory’ option. Of course, they pulled the old stunt that once they were in office and had access to the ‘books’ they discovered, surprise surprise, that the state of government finances were even worse than they had imagined and that meant it was all to play for, which justified them taking tougher than planned actions. Every week passes since, it seems, when the tough talk gets tougher and core promises are abandoned. Tory policies that are the anathema of a progressive policy stance – such as the two-child benefit cap – will remain. And other Tory policies that were more ‘Labour like’ in nature will go – such as the Winter Fuel Payment received subsidy – will be severely cut back. There are many criticisms that I have made of the Chancellor’s stance (see previous blog posts) based on the absurdity of constructing the British government’s finances as equivalent in principle to the finances of a household issue. But, in addition to those more elemental issues, there is another matter that I have not seen addressed by the mainstream media nor the actual politicians relating to the proposed austerity. The whole discussion appears to be waged in a vacuum – context free. It is as if the current policy position, which the Chancellor claims is shocking and unsustainable, is divorced from the current broader economic reality in Britain. And that construction means that poor policy decisions will be made that will damage the material prosperity of the nation.

By way of background, the Winter Fuel Payment was introduced by Labour in 1997 and is paid to eligible pensioners in the UK to help them get through the Winter cold.

Around 11.4 million pensioners received the payment in 2022-23, which is worth a few hundred pounds.

The changes that are forthcoming will exclude around 10 million pensioners in England and Wales who are currently receiving the benefit.

Like all payments that are made on a universal basis, there are arguments that can be made about scope – why should the rich get them, for example.

But the evidence appears to be that the proposed means-tested thresholds that the Labour government is planning will deny several million people who will face hardship as a result.

My recent blog posts on the more elemental issues are:

1. British Chancellor fails the basic test – language is meant to impart meaning (August 1, 2024).

2. The Bank of England does not need a tiered reserve system for the Government to avoid austerity (August 5, 2024).

3. The new British Labour government will have to abandon its fiscal rule or deliver very little (July 24, 2024).

4. British Labour Party once again tripping over their nonsensical fiscal rules (June 20, 2024).

Now let’s go back to the main issue that I want to highlight today.

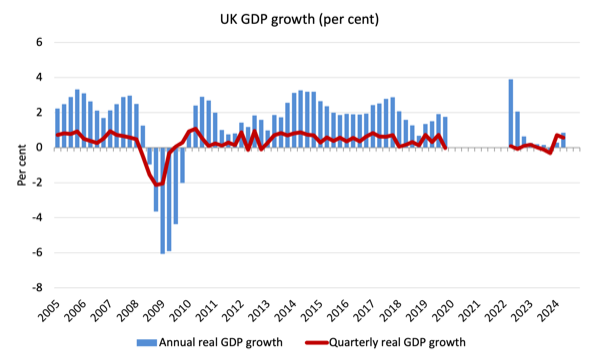

On August 15, 2024, the British Office of National Assessments released the latest National Accounts data covering the June-quarter 2024 – GDP first quarterly estimate, UK: April to June 2024 – which showed that the UK economy grew by 0.6 per cent in that quarter, after recording a fairly robust 0.7 per cent increase in the first-quarter 2024.

It also shows that GDP per head (in real terms) grew by 0.5 per cent in the first-quarter 2024 and by 0.3 per cent in the June-quarter 2024.

So, on average, British people are enjoying higher incomes.

The implied price measure in the National Accounts has fallen significantly and was 0.3 per cent in the June-quarter.

The first graph shows the annual and quarterly growth rates from 2005 to the June-quarter 2024 (with the COVID-19 quarters between March 2020 and March 2022 excluded as outliers).

I left the pandemic period out because it distorts the rest of the data.

After several quarters of very low growth, 2024 has seen an improving outlook in terms of growth.

The question that has to be asked then is: What is driving that growth?

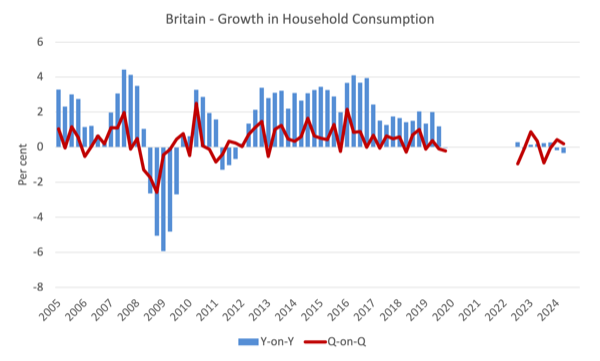

The following graph shows the annual and quarterly growth in household consumption expenditure (real terms) since the March-quarter 2005 (with the pandemic quarters excluded).

Over the last several quarters, household consumption expenditure growth has been very low or negative.

In the first two quarters of 2024, it has improved a little 0.4 per cent in the March-quarter and 0.2 per cent in the June-quarter.

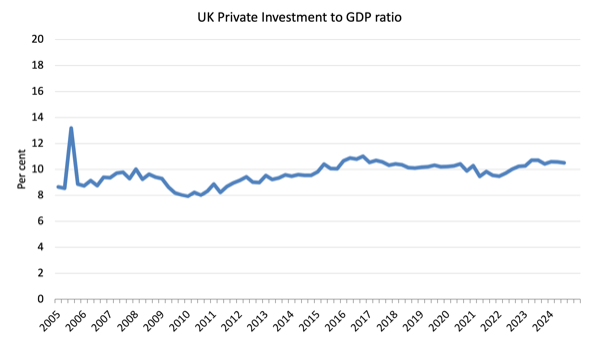

What about private capital formation (business investment)?

The investment ratio has been largely stable around 10.5 per cent of GDP for the last decade or so.

The ONS say that:

Within GFCF, business investment is estimated to have fallen by 0.1% in Quarter 2 2024, following growth of 0.5% in the previous quarter. Compared with the same quarter a year ago, business investment is estimated to have fallen by 1.1%.

And the net trade sector was in deficit equal to “2.7% of nominal GDP in Quarter 2 2024.”

So these elements of total expenditure were not helping growth.

Contributions to growth

Of the 0.57 per cent growth recorded in the June-quarter 2024, the contribution from the public sector (both recurrent and capital expenditure) was 0.39 points, a significant proportion.

Government recurrent expenditure contributed 0.3 points to the overall growth figure, while government investment (capital expenditure) contributed 0.09 points.

Thinks about this in the context of the recent reports – driven by statements from Labour Cabinet ministers – that the government will “take further difficult decisions”, over an above those already announced (Source).

The cited article quoted the Cabinet Office Minister as saying:

It is about making tough decisions, because we saw what happened a few years ago when the public finances were lost control of. We don’t want a repeat of that, and these are the difficult decisions that a chancellor has to make now.

Now we are back to the elemental ignorance issue.

What does losing control of public finances mean?

It is one of those stupid vacuous statements that the general public get spooked by which has no sense to it.

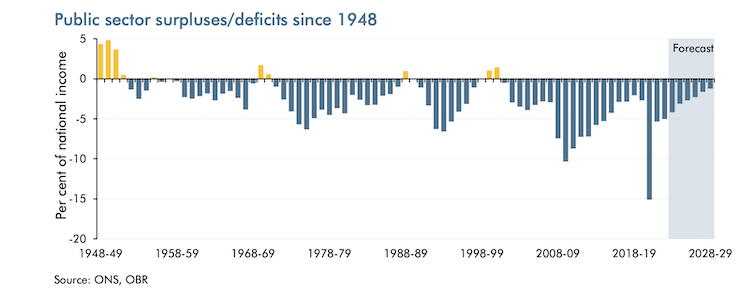

The data shows that the fiscal position is unexceptional, cycling through the rise and fall as dictated by the spending decisions of the non-government sector.

This graph from the OBR publication – A brief guide to the public finances (published April 25, 2024) – was produced before the election.

The OBR write that:

In 2024-25, we expect a deficit of £87.2 billion or 3.1 per cent of national income. This is a sharp fall from the 2020-21 peak of £314.7 billion, which was the highest since the second world war. Over the five-year forecast, we expect the growth in receipts to outpace that of spending and the deficit to fall …

Movements in the budget deficit are in part the result of the ups and downs of the economy. When the economy is strong, the deficit will be lower as taxes receipts increase and welfare spending costs are reduced. The opposite is true when the economy is weak.

The OBR also notes that:

1. “The UK government raised slightly more revenue relative to national income than the US, Japan and Canada, but less than Germany and Scandinavian countries like Denmark and Norway.”

2. “Public spending as a share of national income in the UK is slightly above the average of other industrial countries – the UK spends more than the US and Japan, but much less than Italy or France.”

3. The UK deficit is just above the average of the OECD nations – not by much.

So, even if we just considered this narrow data – “out of control” is not a descriptor that comes to mind.

Then think about the relationship with the other major macroeconomic sectors – the external sector and the private domestic sector.

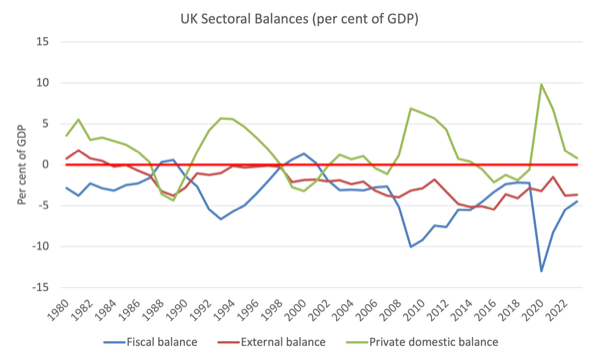

The next graph shows the so-called sectoral balances from 1980 to 2023 (using IMF WEO data).

If you are unsure how to comprehend this data please read this blog post which derives the sectoral balances from first principles – The 714th and Final Weekend Quiz – December 31, 2022 – answers and discussion (December 31, 2022) – refer to the answer for Question 3.

The summary relationship is that:

(G – T) = [(S – I) – CAB]

or in words the government fiscal position (G – T) must equal the difference between the private domestic balance (S – I) and the external balance (CAB).

That is not an opinion.

It is an accounting fact derived from the way national accounts data is collected and presented.

The other way of saying that is that the sectoral balances equation says that total private savings (S) minus private investment (I) has to equal the public deficit (spending, G minus taxes, T) plus net exports (exports (X) minus imports (M)) plus net income transfers.

The point is that if there is an external deficit, which for the UK has been constant since 1998 (for example), then the external sector is draining demand (spending) from the economy.

And, a private domestic surplus (net overall saving) also drains demand from the economy.

The only way the economy can then grow is if the fiscal balance is in deficit and at greater than the spending drains from the other two sectors.

You can easily see that after the relatively large fiscal deficits during the GFC, provided the GDP (income) support for the private domestic sector to increase saving overall while the external sector was in deficit.

As the Tories pursued fiscal austerity in the period between the GFC and the pandemic, and the external balance moved into slightly higher deficit, the capacity of the private domestic sector to save overall vanished.

Private sector indebtedness rose substantially and was the only reason growth was possible in the face of the fiscal austerity .

That, of course is an unsustainable growth path because eventually the private balance sheets become too precarious and cuts backs in private spending are necessary to reduce the risk of insolvency.

You can also see that with the external position still in deficit, the attempts by the Tories to reduce the fiscal position has been associated with a decline in the private sector saving position.

The only way the British economy can sustain growth at present with the planned fiscal cutbacks is if the private domestic sector plunges into deficit and builds up ever increasing levels of debt.

It is a recipe for disaster.

Conclusion

The point is that the macroeconomic sectors are intrinsically linked and while the government celebrated the positive growth performance in the first two quarters of 2024 it failed to acknowledge that that performance was only possible because of the fiscal settings.

In other words, the fiscal position has been functionally driving growth and without on-going GDP growth, the government hasn’t a hope in hell of going close to its fiscal rule targets.

Withdraw the fiscal support – as has been announced – and the British economy is heading back towards recession quickly.

The monthly GDP data suggests that growth in June itself was zero on the back of early policy choices.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2024 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.