One source of annoyance over the past year has been the blind media parroting of national and local polling. These are presented without context, framing, and, most importantly, an acknowledgment of the past track record—just blind repetition of useless “data.”

By failing to mention pollsters’ abysmal track records, the media presents a wildly distorted view of future election results.

Indeed, polling a year ahead of elections frequently focuses on candidates who do not end up on the ballot. Recall in 2007, the polls had a head-to-head featuring Rudy Giuliani and Hillary Clinton (neither became their party’s 2008 nominee). November 2023 polls showed Biden vs Trump. We know how that turned out.

But there is an even bigger polling problem, one that is unlikely to be solved anytime soon: Our own inability to forecast our future behaviors.

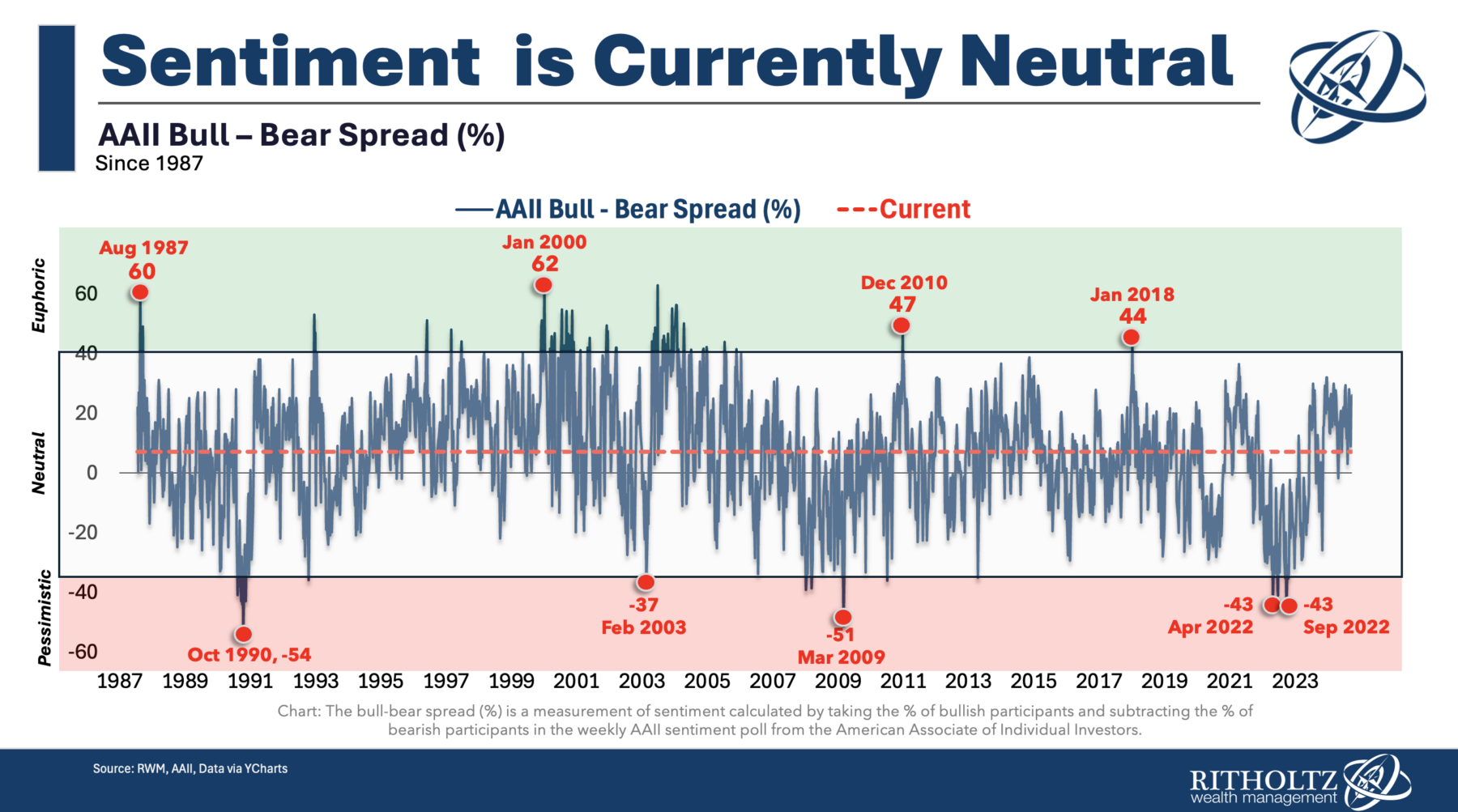

A quick caveat: I am not a polling expert, but I have spent decades studying sentiment data in markets. Long-time readers know that — except at extremes — I find very little usable information in Sentiment data. The reason is that Sentiment measures suffer from problems similar to political polling. (Behavioral economics provides insight into both surveys and modern polling errors).

Sentiment has five key issues that make it problematic. It is:

1. Backwards looking

2. Emotionally charged

3. Operates on a substantial lag

4. Requires accurate self-reporting

5. Highly dependent on precise phrasing of questions

That’s just about basic market, economic, and asset allocation questions. My experiences interacting with many investors over time suggest that people tend to have a fluid sense of their own sentiment, overly dependent on what just happened in markets. Our ability to self-report our bullish or bearishness is faulty. It typically reflects your recent portfolio changes, not our true future expectations. Sentiment fails to measure these issues accurately.

To those five basic sentiment issues, political polling has additional problems:

1. Landline phones

2. Voter intentionality

3. Mobile phones & Caller ID

4. Voter turnout

5. Voter participation

Let’s briefly consider each.

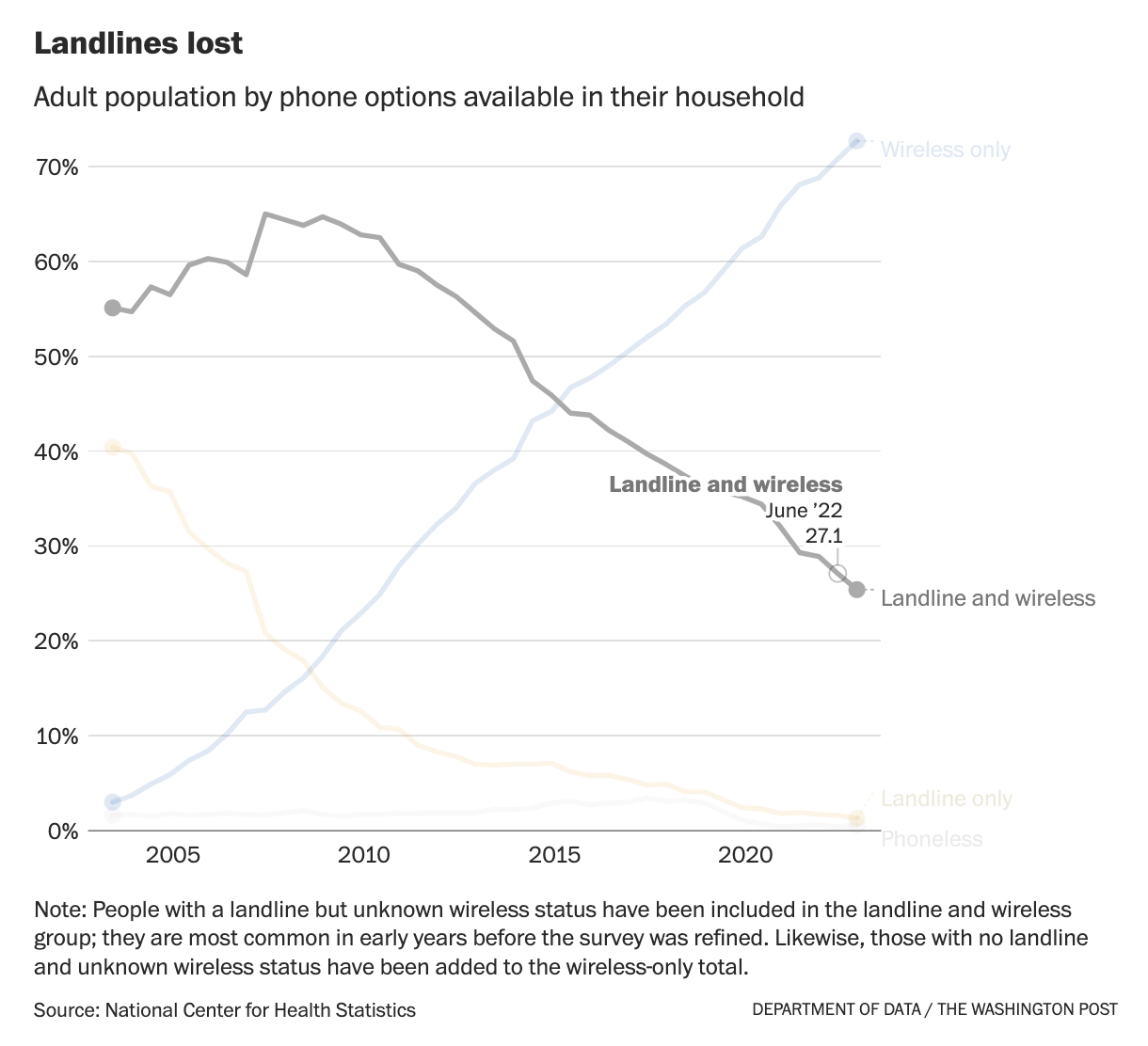

1. Landlines: In 2000, 95% of American households still have a landline phone. Today, it is merely 27%.

1. Landlines: In 2000, 95% of American households still have a landline phone. Today, it is merely 27%.

Losing three-quarters of households is an enormous decrease, and this radically impacts who pollsters can reach. (I am ignoring text and online polls as they are even worse than phone polls). It’s fair to conclude that this makes creating a representative pool of American voters very challenging.1

2. Intentionality: I believe most (many?) people who respond to polls answer honestly. The problem is, people often don’t know what they genuinely believe. (Behavioral finance helps explain why this is so).

Everybody is focused on the undecided. Yes, these “Persuadables” matter. But my guess is they make up less than 7% of voters – maybe even less than 3%. What truly matters to outcomes is who and how many people actually cast a vote. Regardless of whether you are a hardcore political partisan or an independent, you may say you are going to vote — but the data shows that a third of you fail to do so. This behavior is what swings presidential elections.

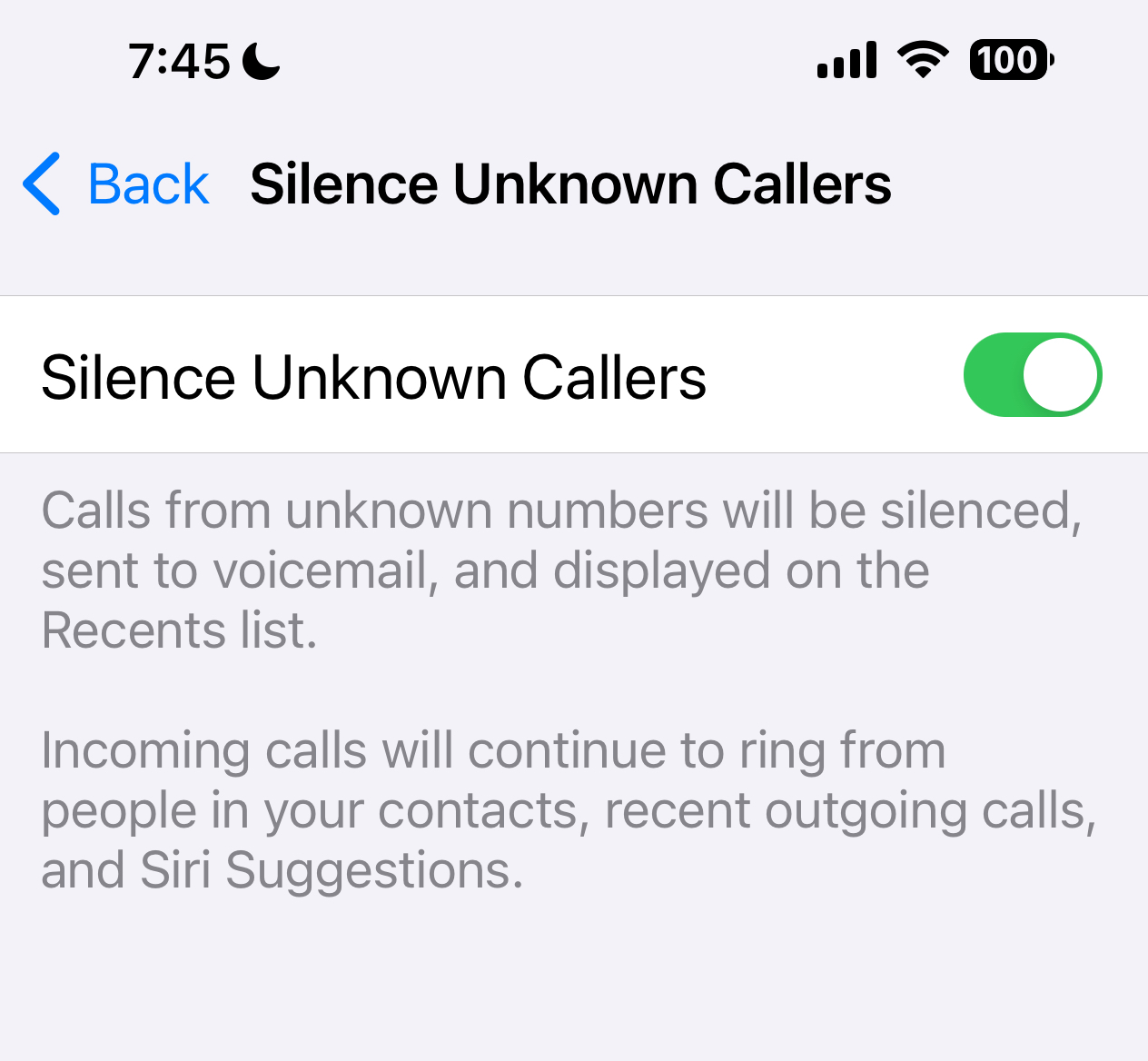

3. Mobile phones (Caller ID): Who is answering unknown calls on their mobile phone? Unless you are expecting a call from someone whose number you don’t have – delivery, contractor, doctor, etc. – your phone (like mine) is probably set to “Silence Unknown Callers.” These go straight to voicemail — and if they don’t leave a message, its probably spam.

3. Mobile phones (Caller ID): Who is answering unknown calls on their mobile phone? Unless you are expecting a call from someone whose number you don’t have – delivery, contractor, doctor, etc. – your phone (like mine) is probably set to “Silence Unknown Callers.” These go straight to voicemail — and if they don’t leave a message, its probably spam.

Who answers calls from unknown people and spends 20 minutes answering questions? I suspect they are not a representative pool of American voters.

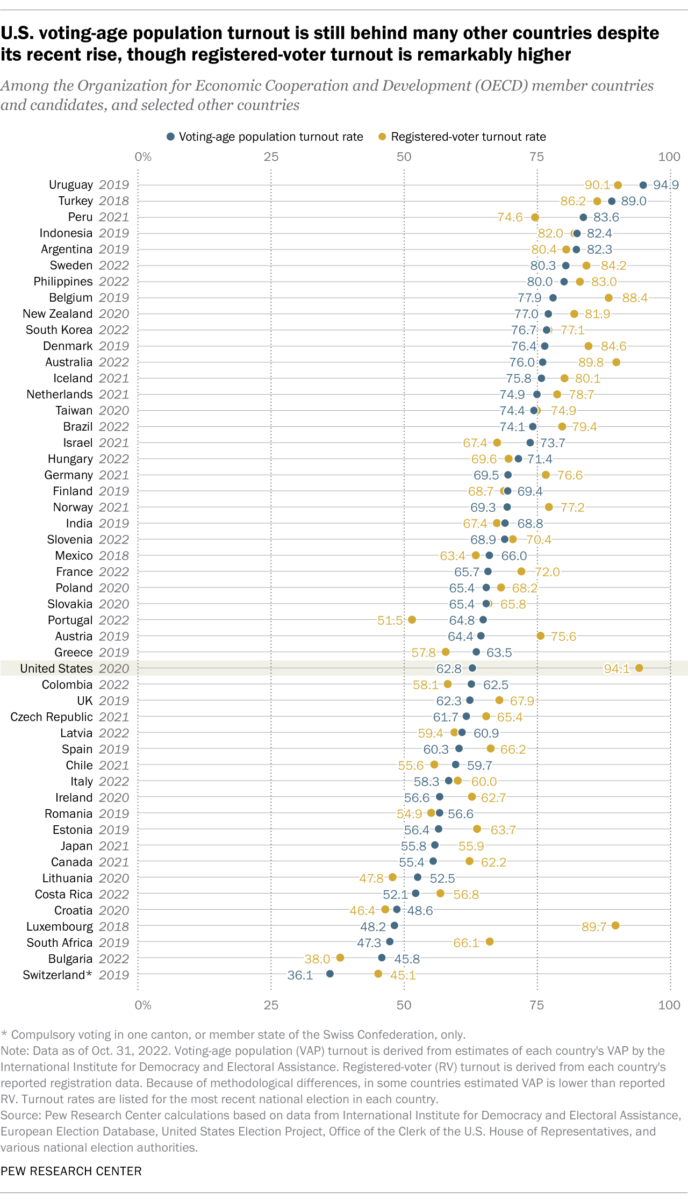

4. Voter participation: The United States has one of the lowest percentages of eligible voters who actually participate in presidential elections (it’s even worse for state and local elections, as well as non-POTUS election years).

PBS, citing data from the United States Election Project, reported that “only 36% of registered voters cast ballots during the 2014 election cycle, the lowest turnout in a general election since 1942.”

In 2020, after a massive voter registration drive, the Census estimated that 168.3 million people were registered to vote. This was two-thirds (66.7%) of the total voting-age population. Most modern developed democracies have much higher voter registration rates. The United Kingdom has 91.8% (2019 parliamentary election); Germany, Australia, and Canada also have over 90% of eligible voters registered. Sweden and Japan automatically register citizens once they become eligible—they run a near 100% voter registration rate.

A surprising number of Americans assume they’re registered—and many are not. The 80 million eligible people not registered is a giant variable when it comes to polls. No wonder the margin of error is actually double what is typically estimated.

5. Voter turnout: The key challenge for pollsters is that people have no idea what their behavior will be in the future. This is why polls are merely “fair” a month and “kind of accurate” a week or so out, but they are completely useless a year, six months, or even two months before most elections.

5. Voter turnout: The key challenge for pollsters is that people have no idea what their behavior will be in the future. This is why polls are merely “fair” a month and “kind of accurate” a week or so out, but they are completely useless a year, six months, or even two months before most elections.

Since 1980, turnout in presidential elections has ranged from 50% to 67% of the voting-age population. The 2020 presidential election had the highest voter turnout in decades, at 66.8%, but this still pales in comparison to most other Western Democracies.

Who gets up off the couch, goes to the local school or library, and casts their vote? The answer is a giant unknown. What is known is that a third to half of eligible voters don’t. This is also why a 2-3% margin of error is laughably wrong—it’s much closer to a 6-8% margin of error.

For any early poll to be accurate, it must accomplish 5 difficult tasks:

1. Reach a representative audience

2. Have people accurately self-identify

3. Use unbiased polling questions

4. Receive honest answers

5. Get accurate predictions of people’s own future behaviors.

The first four all create errors – pollsters can take steps to compensate (in part) for those issues, but it’s still fraught with mistakes.

The last one is devastating to polling accuracy.

Behavioral finance has taught us that Human Beings have no idea what they are going to do in the future. Whether it’s a year or 30 days from now, we do not know with any degree of reliable accuracy. We sometimes think we know what we’ll be feeling that day, we want to believe that we will do what we say we will, but at least in the history of finance, we know people are simply terrible at predicting their future behaviors.

How are you going to be feeling one month from now, on Tuesday, November 5, 2024? What’s your physical state of being? Your emotional outlook? Your mental health? Are you excited, depressed, or apathetic? Did you just start or end a relationship? What’s the weather going to be like that day (a surprisingly important aspect of this)?

***

For the past year, I have been having this conversation with various television and radio personalities, analysts, and pundits. They mostly admit to recognizing this to be true. It hasn’t stopped them from ignoring the track record of political polls over the past 10 election cycles. The focus on the horse race, the artificial creation of a competition, is what the media does best. It is not so much that they have a partisan bias — all human beings do — but rather its their commercial self-interest of anything that makes the contest more exciting, artificially or not. TUNE IN NOW TO GET THE LATEST OUTRAGE! It’s sensationalism writ large. The claim that this is a close race seems designed to manipulate viewers into watching more polls, panels, speculation, and opinions. Most of it is useless filler, the rest of it is simply nonsense.

It is disappointing to see core aspects of Democracy replaced with what looks like lazy monetization schemes.

The polling misled people in 2016 (Trump won), they didn’t get 2020 quite right (Biden won by a much larger-than-expected margin), and they wildly blew the midterm elections in 2022 (Red Wave lol). Why people assume it will be anything different this time is simply an ongoing default setting. Perhaps it’s that US media is more focused on elections as sporting-event-like competitions rather than delving into actual issues, because sports is what American media does best.

Attention-grabbing click-bait rather than policy analysis is not a great way for the media to cover “Democracy.” The repercussions have been having a negative impact now for decades…

__________

1. I have wanted to cancel my landline for years, but, I live in an area with poor cell reception—I get calls at home on the mobile via Wi-Fi. If the power goes out and the backup generator does not kick in, we can’t even call our local provider to alert them we have lost power.