Paul Samuelson is credited with the quip that, “The stock market has predicted 9 out of the last 5 recessions.”

You can credit Ben Carlson with a new variation on this quote:

The stock market has predicted 1 out of the last 0 recessions.

No one ever truly knows what the stock market is pricing in at any moment but it sure felt like it was pricing in an imminent recession in June when the market was down more than 20%.

I know a lot of people think we’re in a recession right now.

I don’t know many recessions that include more than 500k jobs growth in the latest monthly reading and more than 3.3 million jobs in the first 7 months of the year.

Maybe that’s the reason stocks have recovered a decent chunk of that lost ground in recent weeks.

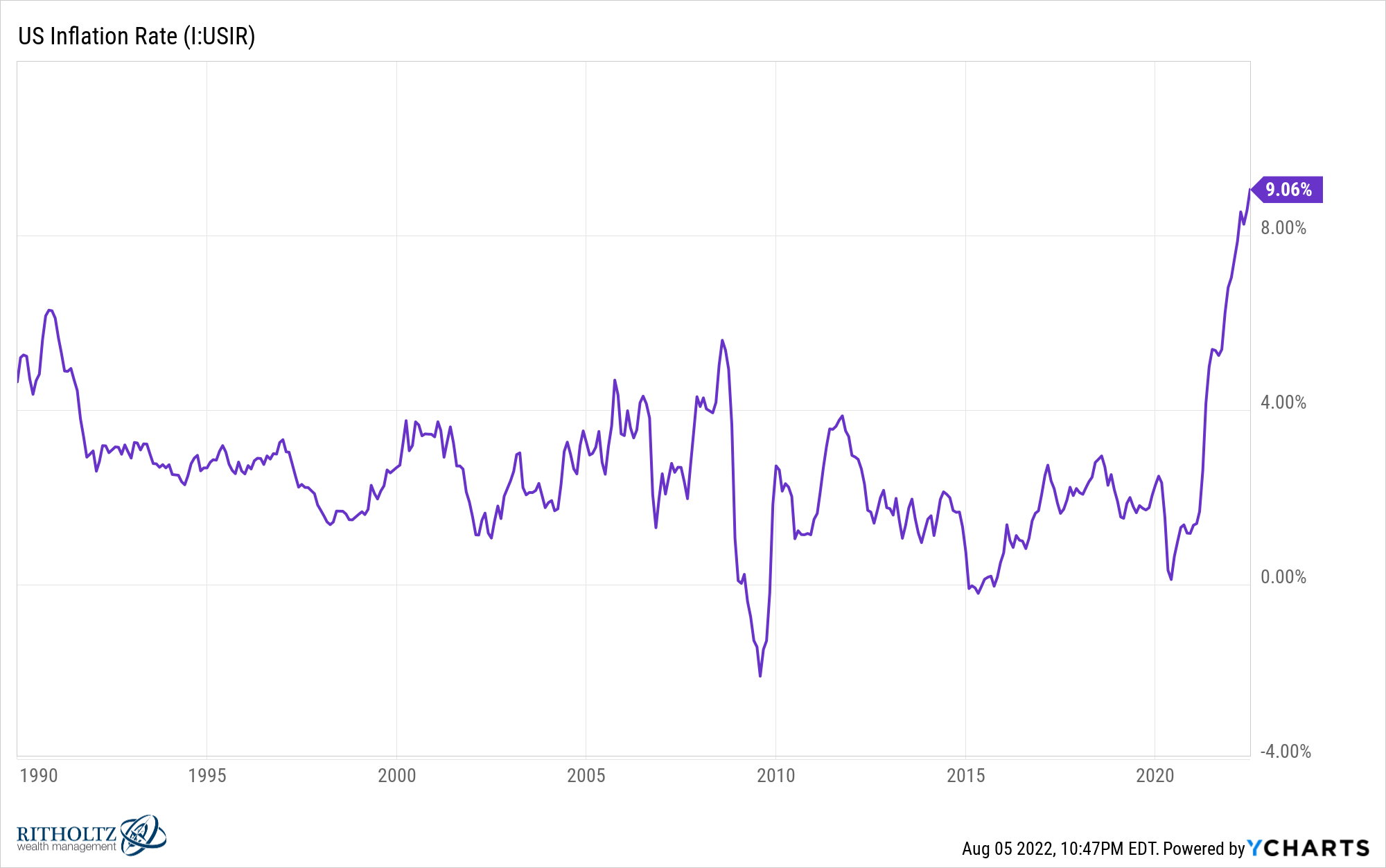

Yes, inflation is high. No, the economy is not perfect at the moment (it never is). Yes, the Fed raising rates could cause a recession in the future. But no, it would be difficult to call this current situation a recession.

Here’s the problem: the fact that we’re even having this Ross and Rachel moment (will they/won’t they) with the economy is not a great sign.

If there is such a thing as “normal” when it comes to the economy the current situation is the furthest thing from it.

Let me count the ways…

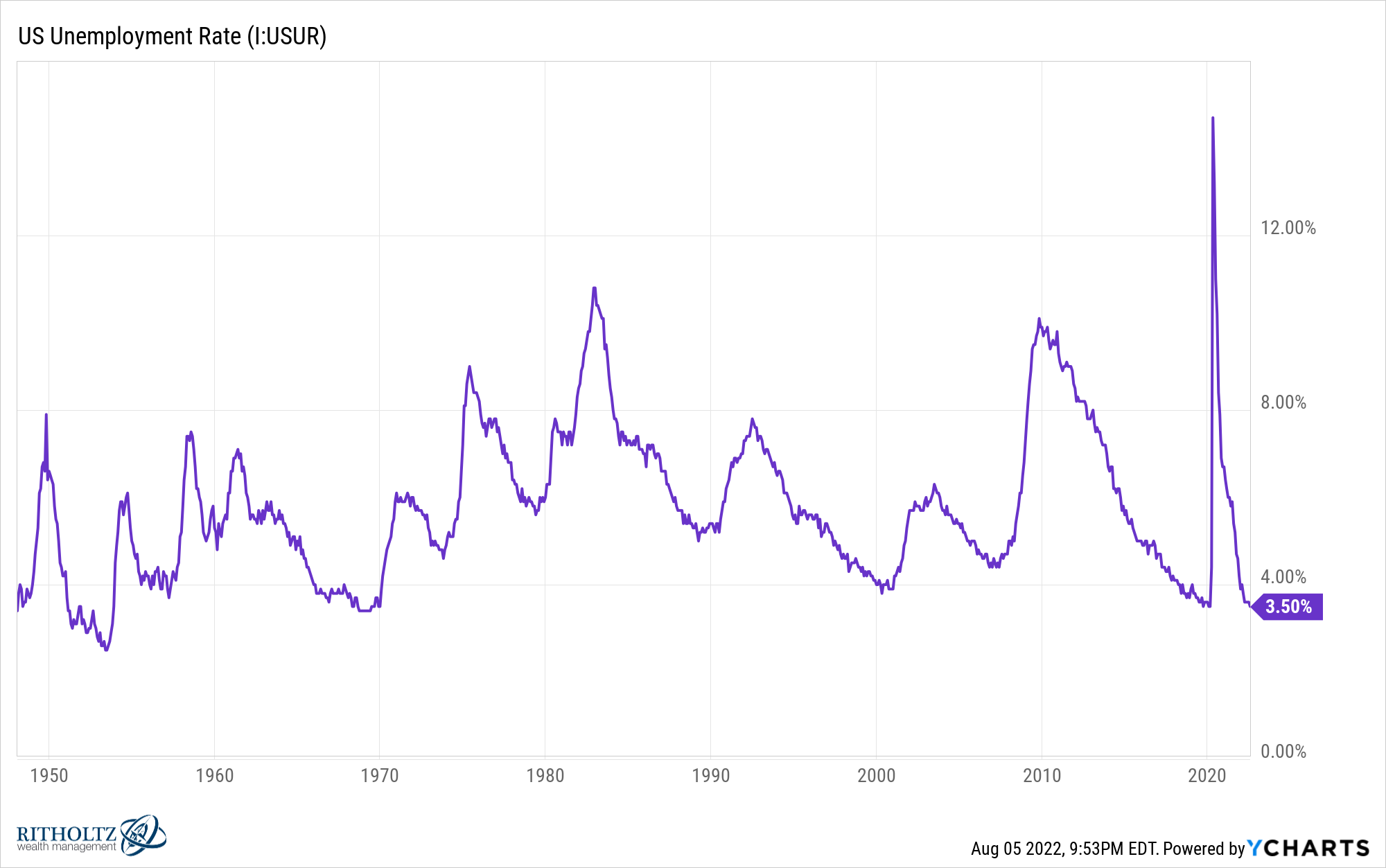

The unemployment rate is now lower than it’s been in all but 5% of readings since 1948:

In January 2020 the unemployment rate was 3.5%. It then shot up to 14.7% during the onset of the pandemic and has now round-tripped back to 3.5%.

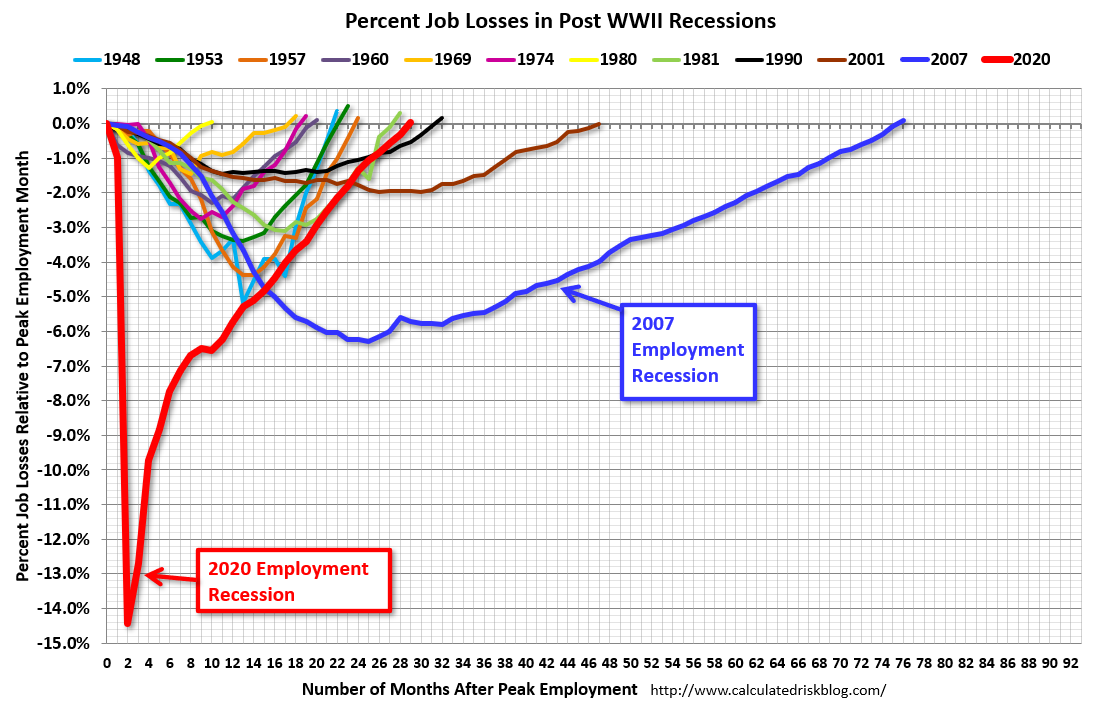

The speed of the moves in both directions is unprecedented (chart vis Bill McBride):

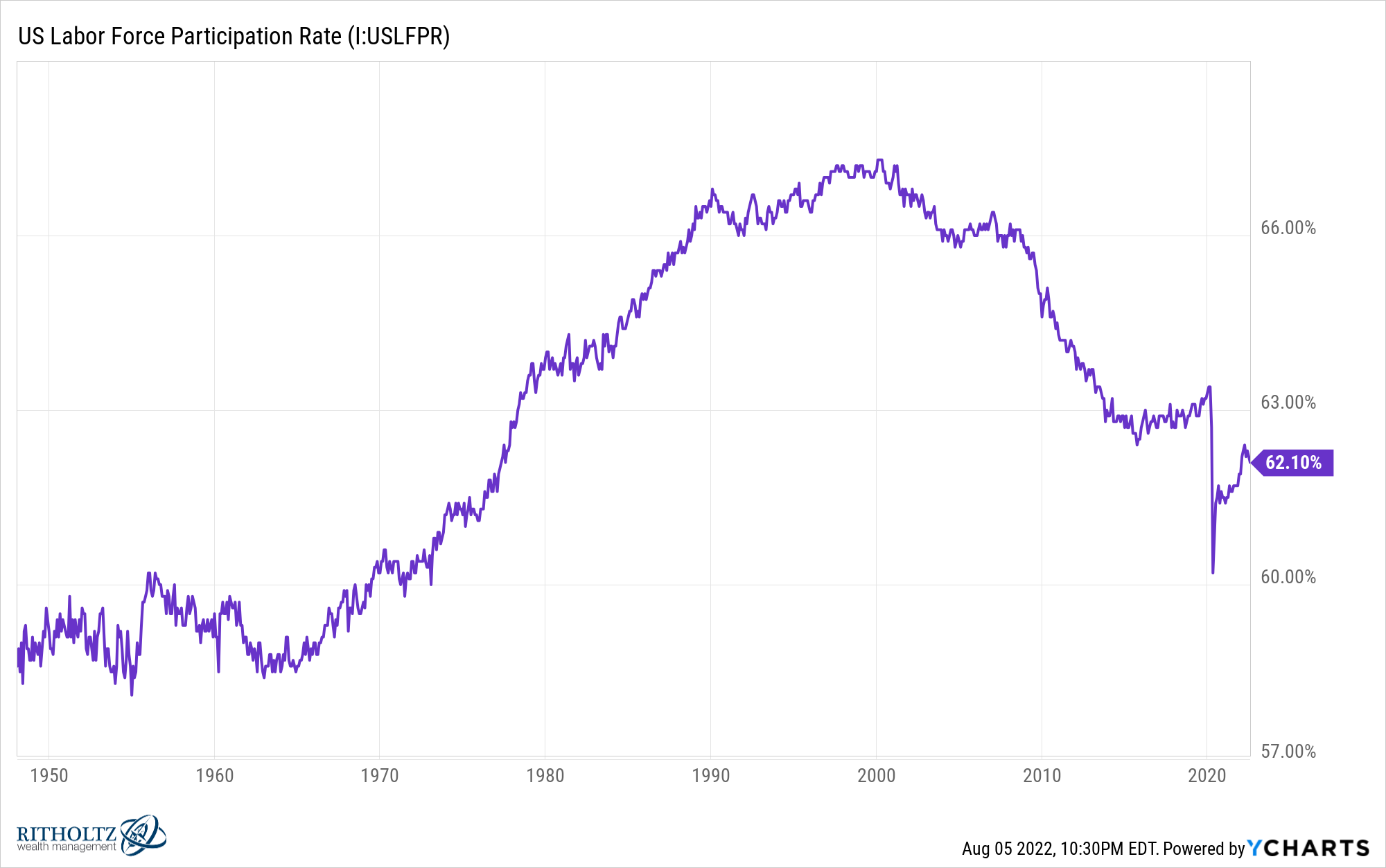

While the labor market feels scalding hot, it’s far from a complete success. The labor force participation ratio is still below pre-pandemic levels:

You can explain some of this shortfall with retiring boomers but not all of it.

Productivity numbers are also down from a combination of people changing jobs and so much turmoil in the supply chain and service industries from the pandemic.

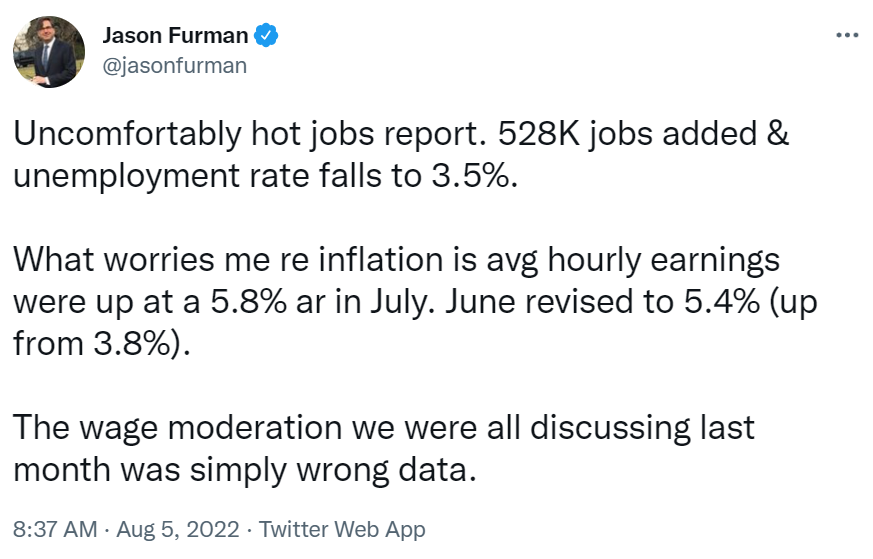

One of the more bizarre aspects of the economics profession is somehow a good job market can be described as uncomfortably hot, as Jason Furman did following the latest jobs report:

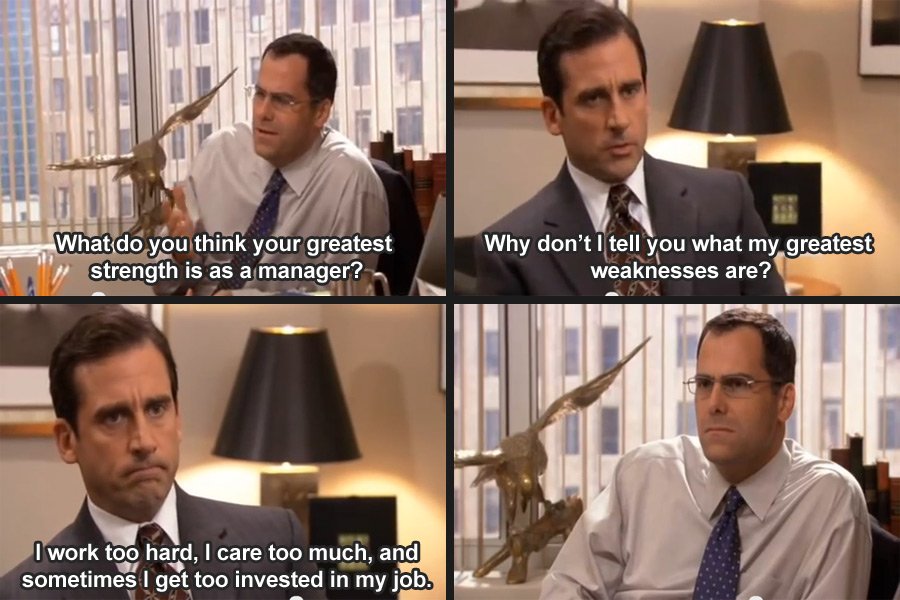

It’s the Michael Scott economy.

Why don’t I tell you my biggest weaknesses as an economy?

Too many people have jobs and wages are rising too fast.

I’m kidding, of course, and not trying to pick on Jason here.

I know why he’s concerned about a hot labor market — inflation this high is not great!

No one wants this.

It’s the catch-22 of the current economic environment.

If the labor market stays strong, that could keep inflation at uncomfortably high levels. But to cool the labor market and inflation, the Fed might have to send us into a recession.

Each scenario would leave millions unhappy.

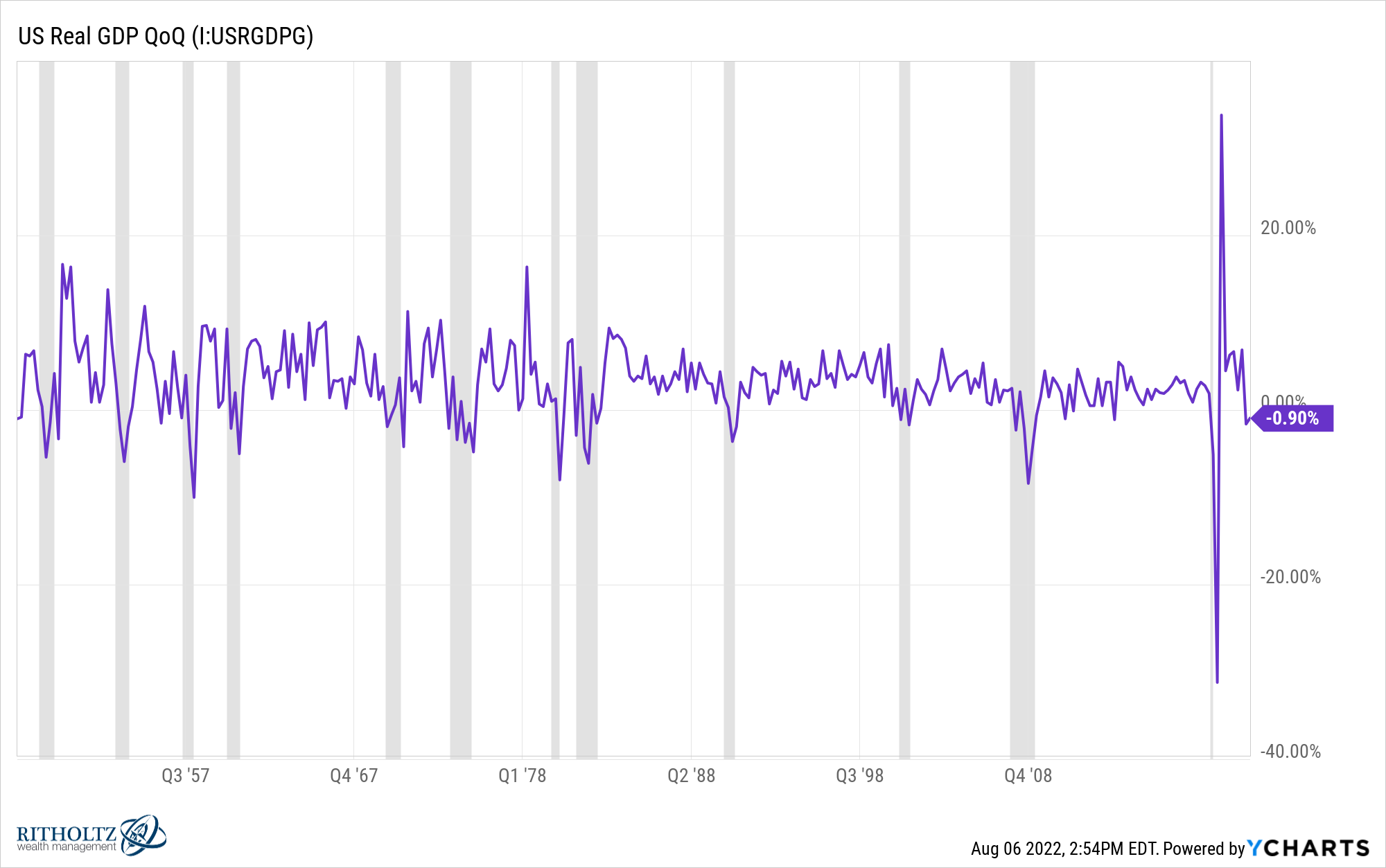

The weirdest economy we’ve ever seen has also added more than 3 million jobs at a time when real GDP fell for two quarters in a row.

The reasons for this decline are wonky — overstocked inventories, imports, cuts in government spending and a moderation in the housing market — but it’s a slowdown nonetheless, even if it isn’t technically a recession.

The last time this happened without going into a recession was in 1947 when real GDP fell in the second and third quarters without triggering a recession.

That instance wasn’t a recession but there was one that started a year or so later in November 1948.

It’s possible 2022 won’t be the starting point of an economic contraction but 2023 or 2024 will be. This is especially true if the Fed continues raising rates.

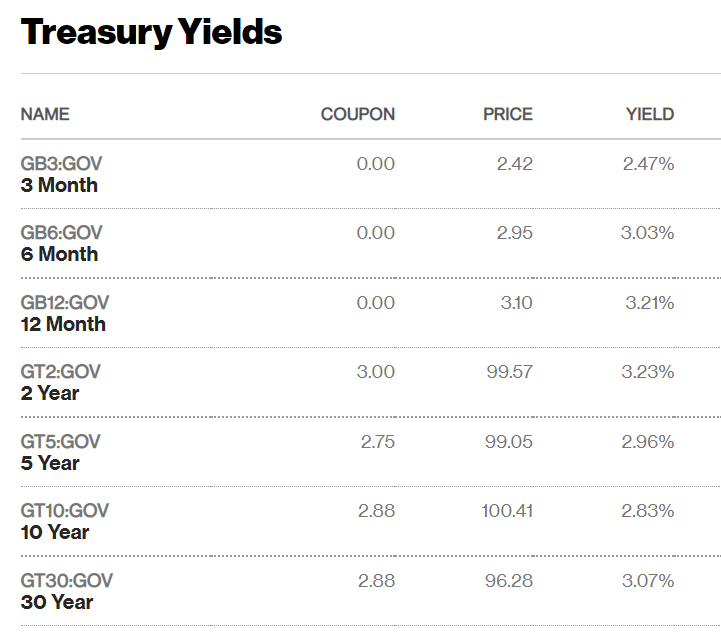

The interest rate market also finds itself in a confusing place.

Just look at the current yields on U.S. government bonds:

The 30 year yield is higher than the 10 year yield. But the 5 year yield is higher than the 10 year. And the 12 month T-bill yield is higher than the 5 year, 10 year and 30 year yield.

That’s not normal. It flies in the face of the risk-reward relationship that should exist in the financial markets.

An inverted yield curve could be signally an oncoming recession or it could mean the bond market is confused right now just like the rest of us.

Maybe the bond market believes the Fed will continue to raise short-term rates but inflation is not a huge worry long-term. Maybe it’s saying the Fed will lower short-term rates sometime in 2023.

Or maybe the bond market isn’t as smart as we all think?

I don’t know what to believe anymore.

It’s not only the level of rates across the maturity spectrum that’s concerning right now; it’s the volatility of the rate moves.

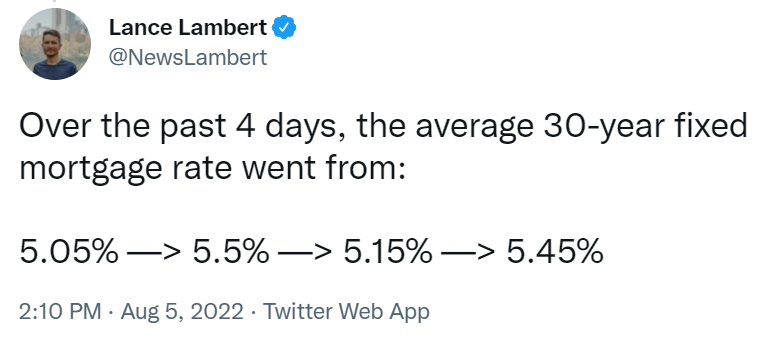

Mortgage rates were around 3% to start the year then quickly shot up to more than 6%. Then they fell back to 5% in a hurry.

Just look at how volatile mortgage rates were during a four-day period this week alone:

Make up your mind interest rates!

One of the most important borrowing rates in the world should not move around this much.

This volatility in borrowing rates is causing some bizarre cross-currents in the housing market as well.

Dan Green from Homebuyer shared two interesting stats about the housing market on a recent update.

The first is that the pending home sales index, which measures the number of purchase contracts between buyers and sellers, plunged to its lowest levels in 10 years (save for the first month of Covid lockdowns) in June.

This makes sense when you consider mortgage rates have doubled just after housing prices saw some of the biggest gains in history. Mortgage payments became unaffordable seemingly overnight.

But the homes that did go under contract in June sold in an average of just 14 days, the fastest pace ever.

So the housing market is definitely slowing, as it should, but there is still a pool of motivated buyers.

There are contradictions like this all over the place.

The bond market is confused. The stock market is confused. The consumer is confused. I’m confused. The only people who aren’t confused either don’t understand what’s going on or aren’t paying attention.

Let’s summarize:

The labor market is on fire. But certain cohorts are leaving and some people are worried about a wage-price spiral.

Inflation is running way too hot. So the Fed is raising rates to slow things down.

If the Fed slows things down inflation should fall.

But to get inflation to fall the economy will likely have to go into a recession.

High inflation is historically bad news for the stock market so investors should welcome a slowdown in the economy.

But recessions are typically bad for the stock market so investors should be careful what they wish for.

If inflation stays high people will be able to find jobs easier and increase their pay (at least nominally). But households absolutely hate inflation with every fiber of their being.

A recession would be way worse than inflation for those who lose their jobs but it would likely offer a reprieve to those who keep their jobs in the way of a slower rise in prices.

I don’t know the right answer to this situation.

Maybe the Fed can thread the needle by bringing inflation back to more reasonable levels without triggering a recession. Anything is possible. Why not a soft landing?

That wouldn’t be my baseline assumption based on historical precedent and how strange the economy has been these past few years.

I might be breaking some rules here but I’m going to use two Michael Scott references in the same blog post.

This exchange between Michael and Jan on the greatest episode of The Office feels like a nice summary of the current environment:

Back and forth we go.

Further Reading:

The Biggest Argument in Finance Right Now