Yves here. Richard Murphy describes how companies are preferring dividends to employee wages as if that’s a bad thing!

By Richard Murphy, a chartered accountant and a political economist. He has been described by the Guardian newspaper as an “anti-poverty campaigner and tax expert”. He is Professor of Practice in International Political Economy at City University, London and Director of Tax Research UK. He is a non-executive director of Cambridge Econometrics. He is a member of the Progressive Economy Forum. Originally published at Tax Research UK

Having taken a quiet Friday afternoon I posted this thread to Twitter this morning:

We are continually being told by Tory politicians and the Bank of England that businesses must not give employees pay rises that might match inflation because this would create an inflationary spiral. But what about dividends? Aren’t they the real cause of the problem? A thread…

The data I am using in this thread was researched by me with @adamleaver and others at Sheffield University Management School and Queen Mary, London, which is available here. https://productivityinsightsnetwork.co.uk/app/uploads/2021/06/PIN-Report-29-6-21-FINAL.pdf

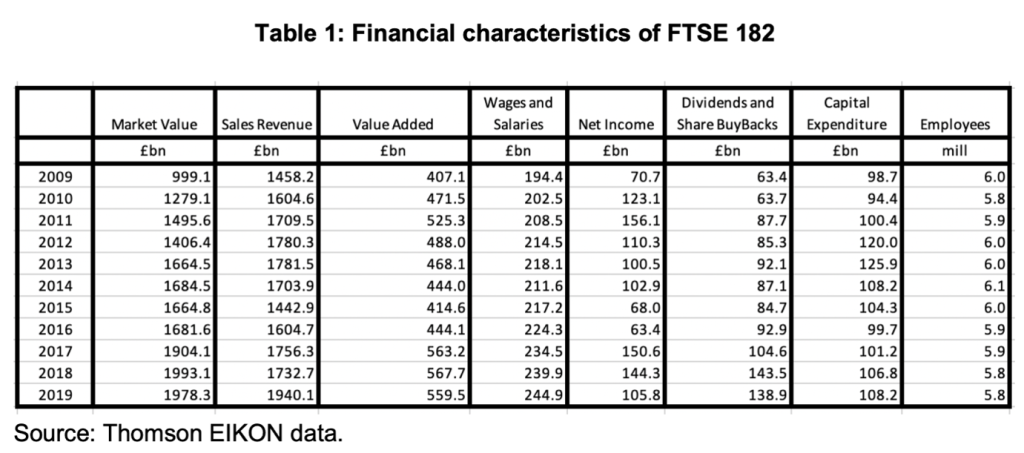

We researched 182 companies that had continuously been in the FTSE 100 from 2009 to 2019 to provide data for the research. Some of these are amongst the biggest companies you’ve heard of. Others are somewhat smaller. The sample is broadly based.

The findings were pretty staggering. What we were looking at was:

- Profitability

- Rewards paid to shareholders

- Employee costs

- Investment

- Borrowing

- What companies were investing in

What was apparent from the data was how odd it was. If 2009 is ignored as a year of crisis the value of these companies grew by 54% in a decade but sales only grew by 21%, and added value was further behind at 18.6%.

What is also apparent is that whilst employee salaries grew by 21%, profits on average fell but shareholder reward payments like dividends more than doubled with those at the end of the decade 218% above those at the beginning.

Notably, the number of employees in these companies was virtually stagnant over the decade and capital investment went up by only 14%, with some variation on the way, with 2012 and 2013 being the best years by far.

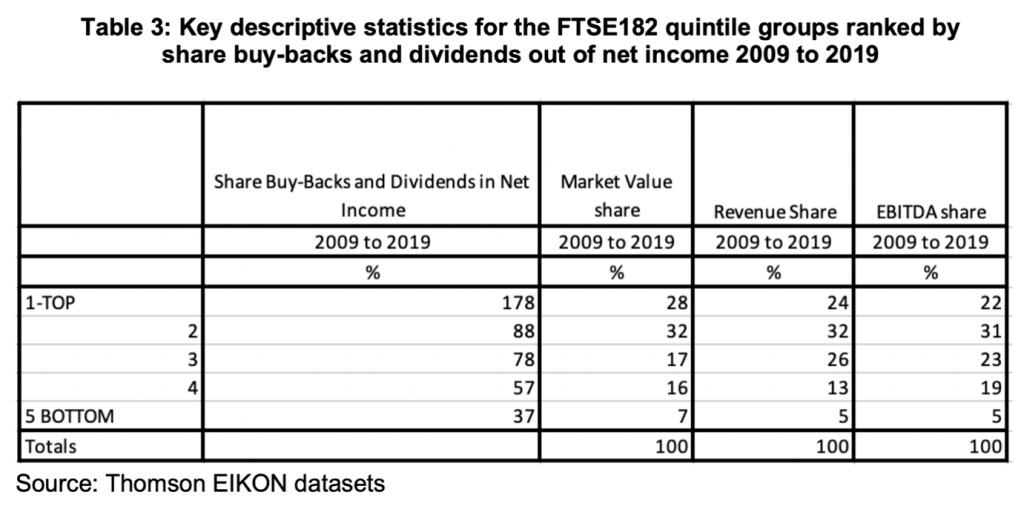

But this is not all that was weird. We then split these companies into five quintiles, which simply means we ranked them into groups of 36 or 37 companies each. We ranked them according to the percentage of their net profits that they paid out to shareholders and got this data:

The top 36 companies paid out 178% of their profits on average. The next 36 or so paid out less: they only rewarded their shareholders with 88% of the profits earned. Together these companies represented 60% of the market value of the companies surveyed and 56% of all sales.

As is apparent from the data, smaller companies paid out less of their earnings to their shareholders. Relatively speaking they were also worth less.

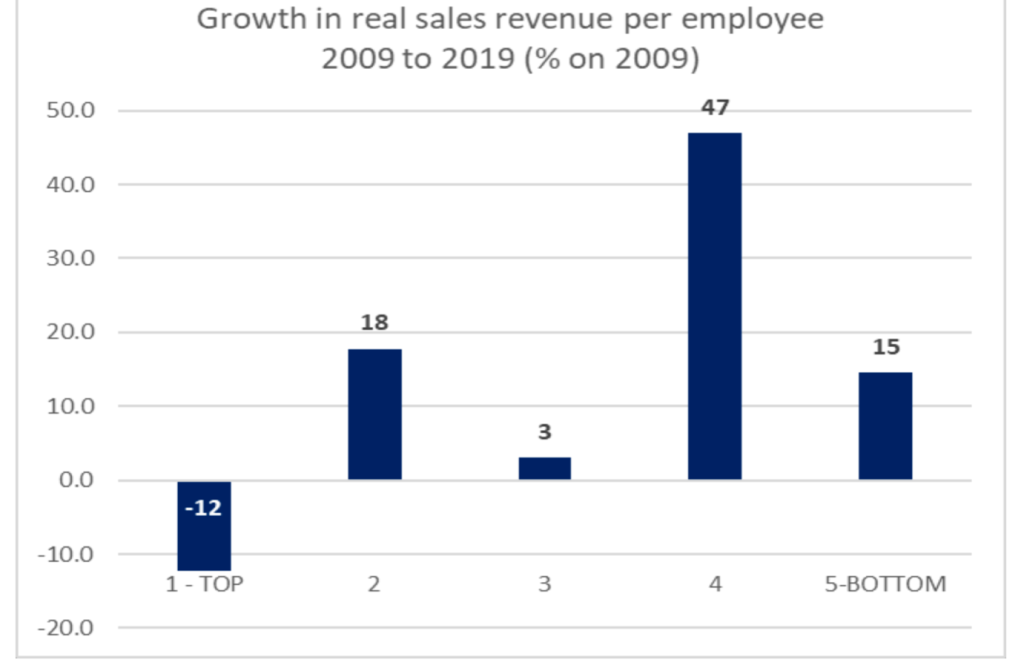

However, looking at the data on how these companies actually behaved suggested that these valuation differences were hard to justify. Take real sales growth, for example where real means that we have eliminated the impact of inflation:

The companies overpaying dividends actually saw their real sales fall. The second group fell well behind the fourth group and hardly bettered the fifth. Value was clearly not related to ability to really grow a company.

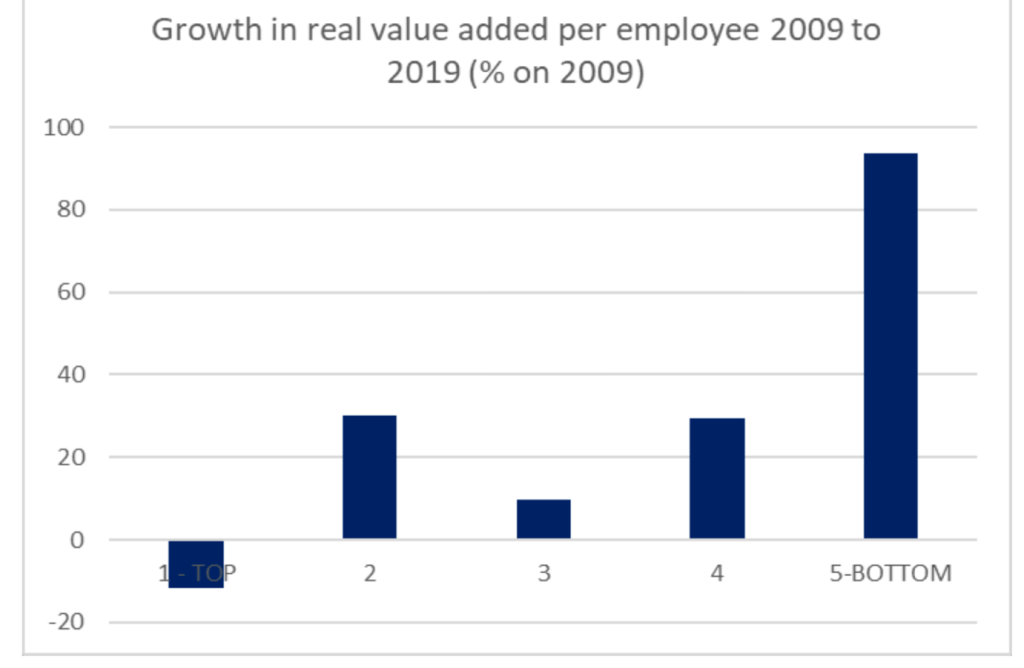

Then we looked at real added value per employee (i.e. again, inflation adjusted). This might be thought of as a measure of just how much of the growth within a company is really generated by its own skills and those of its employees.

Again, the top group did really badly. Their performance actually declined. The companies paying out least by way of dividends out of earnings did best, by a long way.

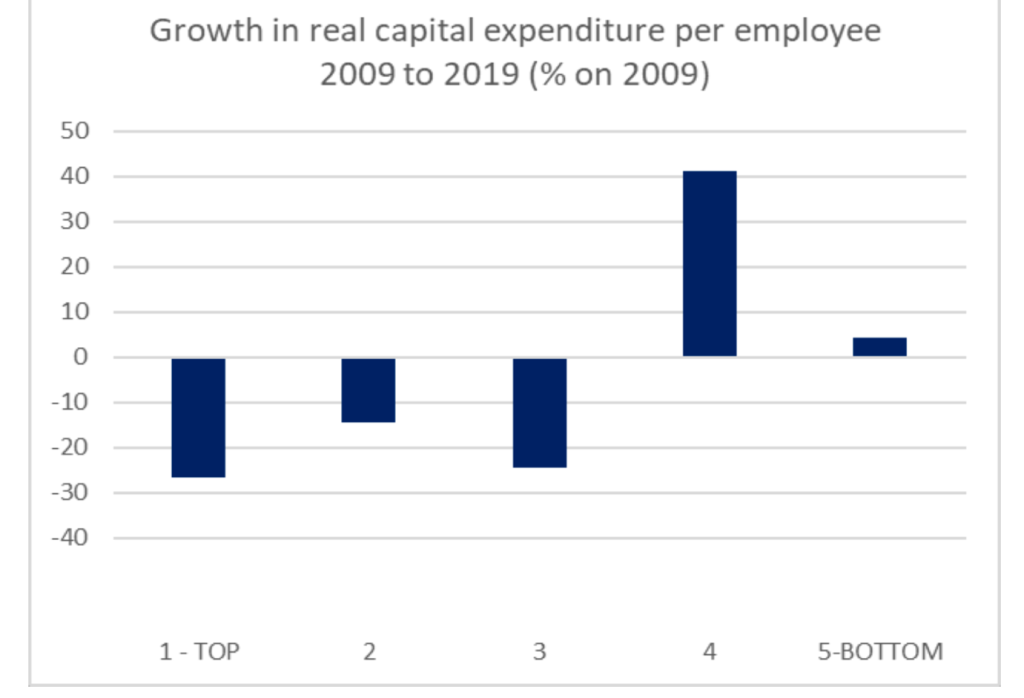

This may not be surprising: we then looked at investment in capital per employee, with the comparison by employee letting us rank the companies consistently whatever their size:

The companies who paid out less by way of dividends invested more in new capital equipment per employee. No wonder their real value added per employee was better.

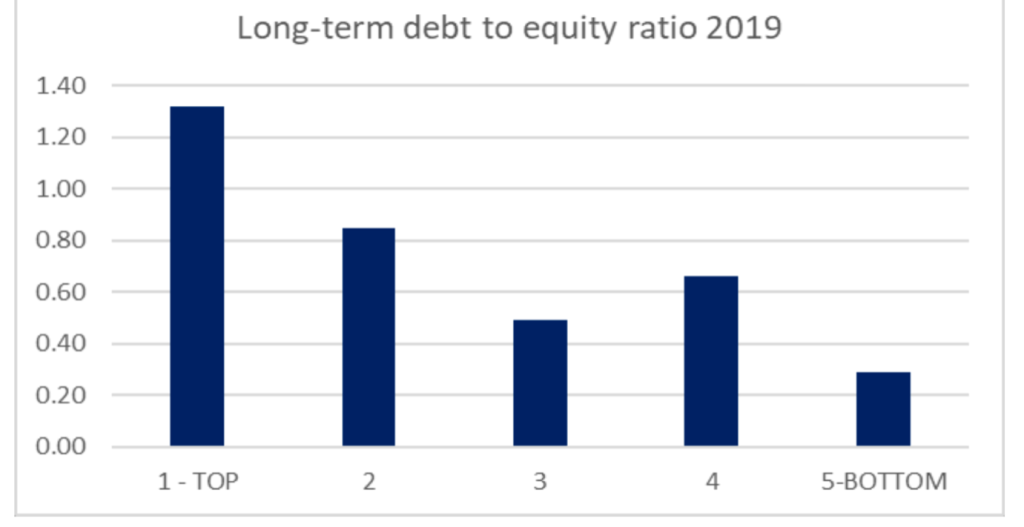

So, then we asked the obvious question, which is how do these companies that pay out more by way of dividends than they earn by way of profit manage it? They do, of course, achieve it by borrowing, much more than average:

The less a company borrows and the more it relies on shareholder funds to support its activities (including profit not paid out by way of dividends) the more resilient it is against financial shocks, because it still has the capacity to borrow when the unforeseen happens.

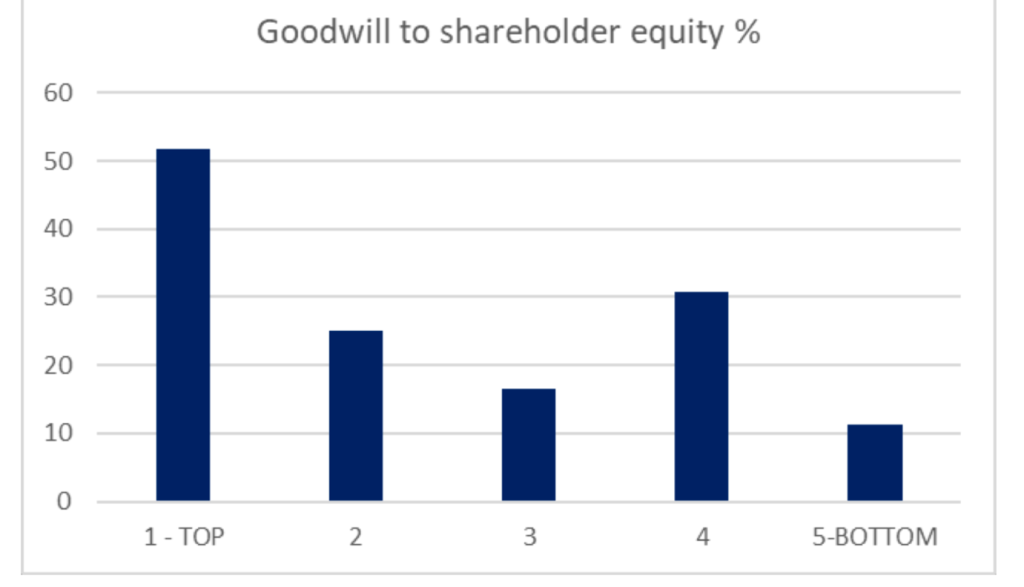

There was another big difference amongst the companies. Those who paid out most by way of dividends had the highest ratio of goodwill to shareholder’s funds on their balance sheets:

Goodwill is the amount paid to buy another company over and above the physical equipment bought. Bluntly, it’s the price paid to get your hands on the future profit another company might make. The high dividend paying companies are much more willing to do that than the low dividend paying companies.

Maybe this is because they know they lack the ability to grow their own companies that those paying fewer dividends seem to possess.

I do not pretend that this research answers all the questions that could be addressed on this issue. It’s also most certainly not investment advice. But it does suggest a number of really important things.

First of all, a majority by value of the FTSE 100 has, over a decade, been paying out almost all, or much more than its profits earned by way of dividends to shareholders, which is staggering.

Second, these companies borrow the money to pay out these dividends. They seek to turn borrowing into excess dividend payments in relation to sums earned to inflate their stock market values, which seems to be working as the companies doing this dominate the FTSE by valuation.

Third, this suggests that these companies are much more interested in financial engineering than they are in actually creating real value within their companies. How they might do this is suggested in a paper I have co-authored here. https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/media/28677/download?attachment

Fourth, as a result these companies under invest, except in buying other companies, in which they might overinvest, creating risk for their shareholders, and employees of course.

Fifth, by looking at those companies that decide not to pay out nearly as much by way of dividend we can see that the behaviour of those companies paying excess dividends is a choice, and not necessity. No law requires them to behave this way, in other words. Their recklessness is chosen.

But, and this is key, the larger companies (by value and sales) who focus on over-paying dividends as if it is their corporate purpose do create real victims in the process. They achieve their result by suppressing wages and real investment, so we have poor pay and productivity.

The companies that overpay dividends also increase their borrowing, putting their shareholders, employees and the economy at large at risk.

And by over-investing in buying other companies rather than in creating real value-added through their own abilities they stress their own balance sheets, and also promote overvaluation of the FTSE as a whole, which is only a short-term gain.

Which brings me to another core issue, which is why do the managements of these companies seek to exploit all those that they engage with, from lenders, to shareholders, to employees, by pursuing these policies? There has to be a reason.

Of course, there is. The management of companies screwing their companies to pay excess dividends do it to inflate the share prices of those companies. And their directors’ bonuses are almost always related to increases in that share price. In that case their exploitation pays.

So, when the argument is made by companies (usually the largest ones) that they cannot pay inflation-matching wage rises, what they’re actually saying is that they want to continue paying inflation-busting, and very often unearned, dividends instead.

The message is that these companies don’t want to pay inflation matching pay rises because they’re not interested in employees, the future of their companies, their sales or keeping anyone happy so long as they can by financial engineering keep turning borrowings into profits.

Not every company is guilty of the financial engineering that is going on. The Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales is guilty of enabling it by the guidance it issues on how dividends can be paid, which lets this abuse happen. And corporate greed is guilty of exploiting that advice.

But the truth is that if the largest companies acted responsibly and stopped driving up dividends by making payments they cannot justify they could make the wage payments the UK economy needs them to deliver now to prevent many of their employees falling into poverty.

If business acted responsibly in this way it would also set the tone for all wage settlements. That it is not doing so is by choice. And that choice must be challenged. Even shareholders are at risk from what is happening. This behaviour must end, and now is the time to stop it.

Simple changes to the law could prevent this: Adam Leaver and I have presented those rules to relevant government departments during discussions on audit reform but big business has lobbied hard to keep this situation, and has won it seems.

As a result the likelihood that shareholder rewards will continue to outstrip pay, whilst fuelling inflation and imposing hardship is likely, and all to feed the greed of managers who seem to get to the top of a company and see their once-in-a-lifetime chance to get rich quick.

Finally, my thanks to co-authors Adam Leaver, Colin Haslam and Nick Tsitsianis and Sheffield University Management School for enabling this work to happen. The opinions here are all my own though.