It’s no longer possible for any reasonable person to deny the existence of human-generated climate change. And as Pakistan suffers under record flooding, Greenland’s ice melts in September, and countries around the world are hit by record-breaking heat wave after heat wave, the effects are starting to become painfully clear. It’s too late to prevent major climate change, but if we make a mighty effort we will be able to limit the damages.

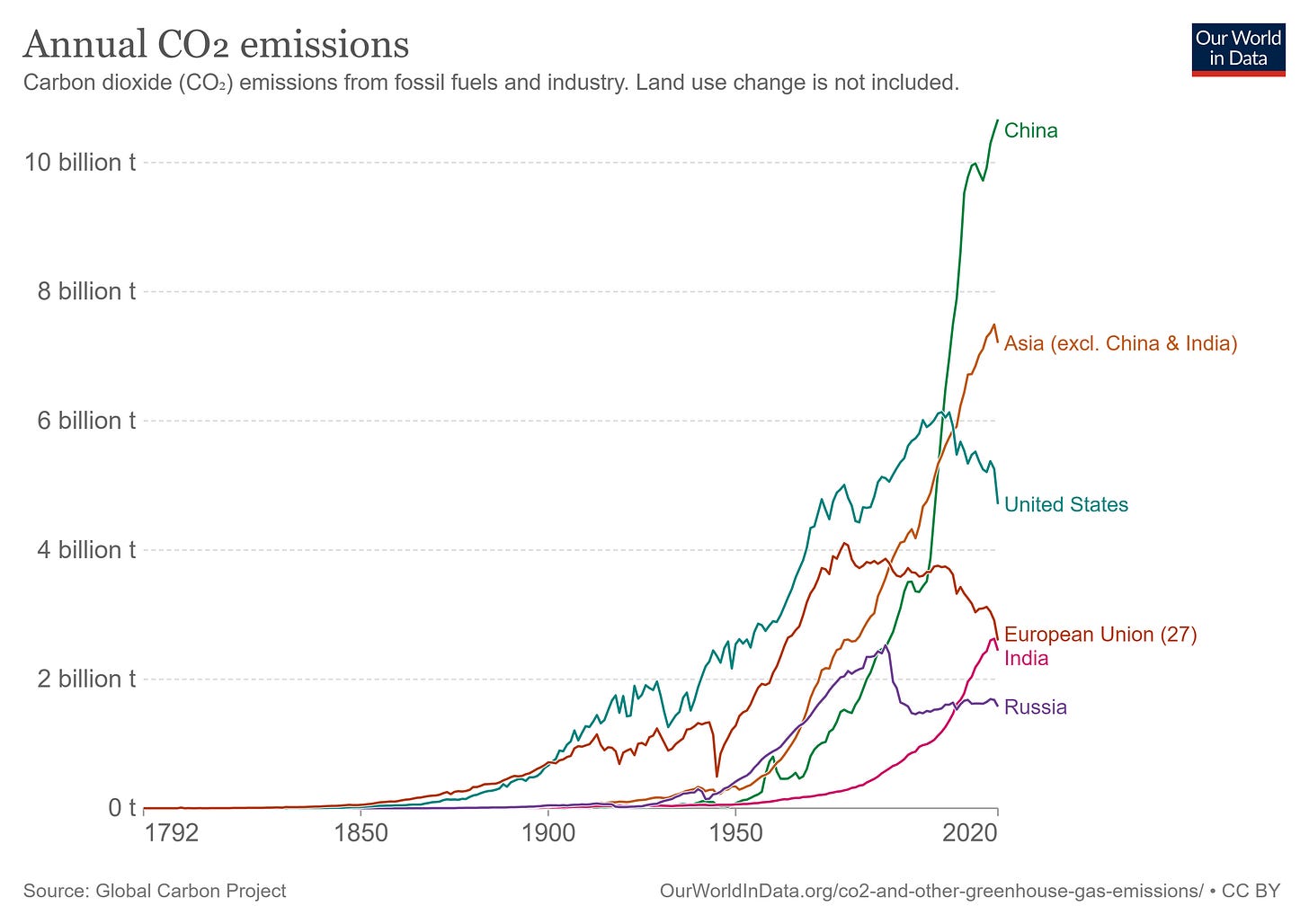

But there’s another uncomfortable reality of climate change that many Americans still strongly resist: The problem is less and less under our nation’s control. The majority of the world’s carbon emissions now come from Asia, with China releasing by far the biggest share.

This doesn’t mean the U.S. is unimportant when it comes to climate, and it certainly doesn’t absolve us of our historical responsibility regarding our past emissions. But it does mean that the locus of control over the climate problem no longer resides in Washington, D.C. Which means that we have to take a global perspective when crafting our climate response, instead of just worrying about cleaning up our own house and letting other people worry about themselves. That will involve reducing the costs of green technologies, working to create international agreements, investing in green energy in other countries, and possibly carbon tariffs. But even with these measures, the decisions that will save the planet or burn it are now largely being made in Beijing.

Many Americans strongly and instinctively push back against the idea that we’re no longer in the driver’s seat when it comes to climate. For some, it’s a moral issue — the idea that the biggest emitter of the 20th century would not bear the biggest responsibility for stopping climate change in the 21st century feels like letting a villain off the hook. For others, the ingrained notion that America is the biggest and most powerful economy in the world is simply difficult to let go. Others instinctively yearn for a feeling that they control their own destiny — that protesting in the streets of D.C. or San Francisco or Seattle can save the planet, even though Beijing is hardly listening. And others simply want to place the blame for all global ills on the shoulders of the United States.

One common idea that allows people to cling to the notion that America is still the world’s top climate polluter is the idea of offshored emissions. Many people believe that the U.S. offshored much of our manufacturing to China and other countries. And thus, they believe, the U.S. is still responsible for the lion’s share of global emissions, because China emits the CO2 to create products for American consumption.

This is not a straw-man argument. Many people believe this! For example, I recently posted a chart similar to the one above on Twitter:

And here were a few of the responses:

I could go on; there are many, many more responses just like this. The idea that the U.S. and Europe reduced our emissions mainly by offshoring manufacturing is a very widespread belief.

And thus, it deserves debunking, because this idea is a total myth.

Typical measures of carbon emissions, like the one above, show emissions from production. But if production is offshored, then emissions can indeed be outsourced.

In fact, climatologists do keep track of how much emissions are outsourced. The Global Carbon Project maintains a database of estimates of consumption-based emissions — the carbon emissions that are necessary to produce the goods and services that a nation consumes.

Consumption-based emissions can’t be offshored. Under a consumption-based measure, if an American buys a TV, the carbon emissions that go into making that TV are allocated to the U.S., no matter where the TV is made. If an American TV factory packs up and moves to China, but the TV still gets sold to an American consumer, then consumption-based emissions are unchanged.

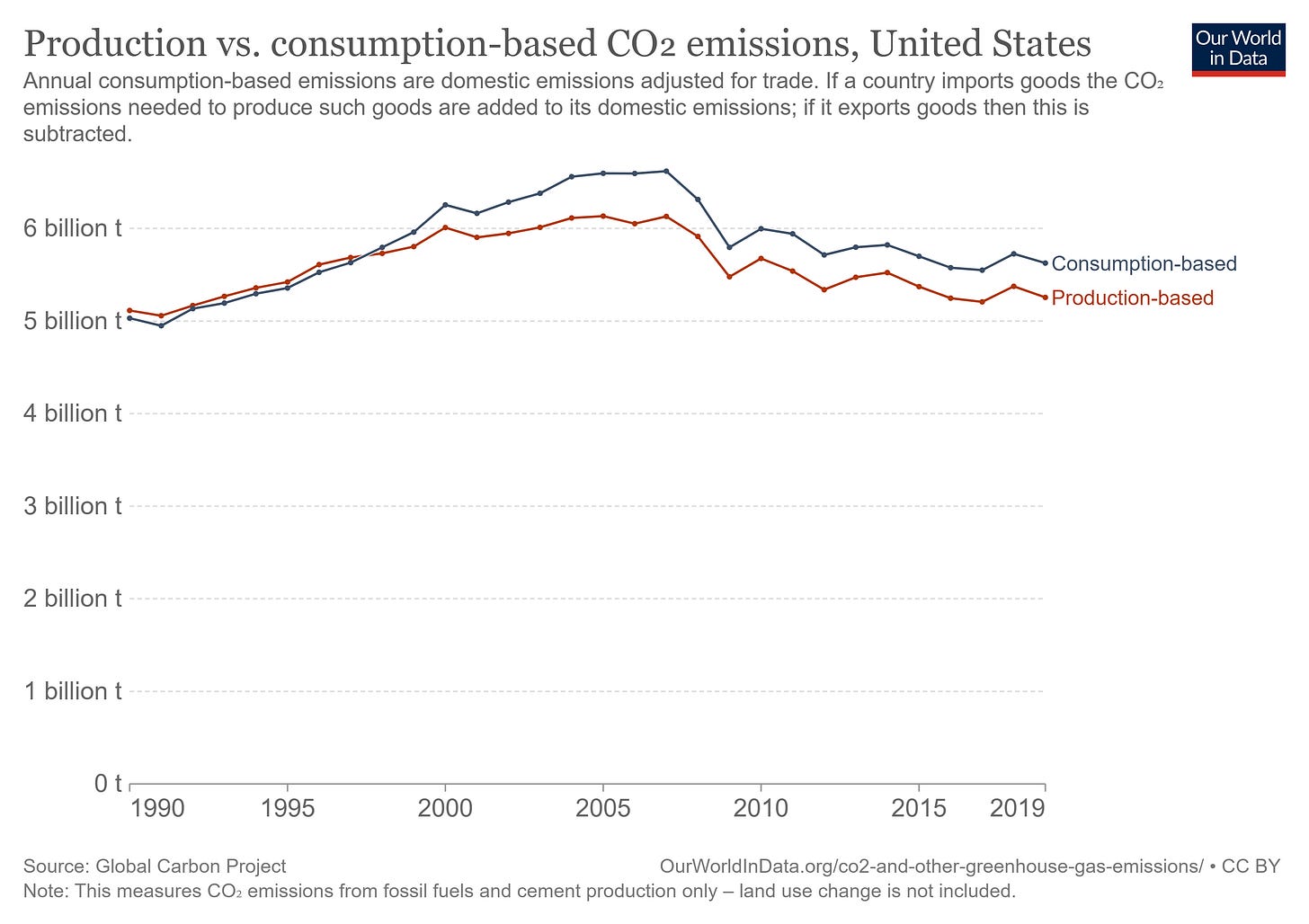

The website Our World In Data has a great page with a bunch of data about consumption-based emissions. And what it shows is that accounting for offshoring just doesn’t make a huge difference in the overall pattern. For example, the U.S. offshores only about 7% of our emissions:

Why such a small difference, given our big trade deficit? The answer is that the stuff we export is pretty carbon-intensive.

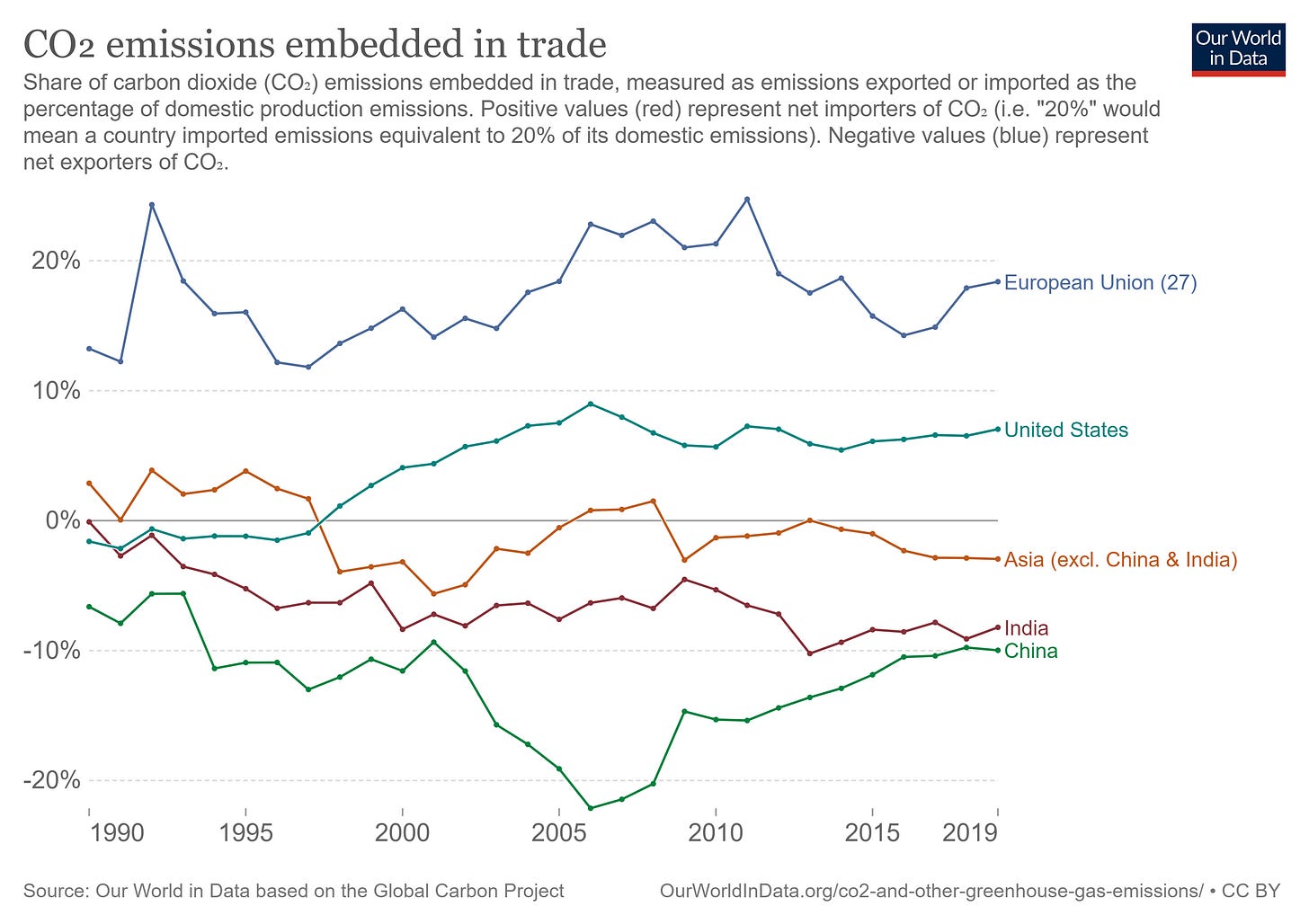

Here’s a simple graph where we can see how much the consumption-based measure changes the picture for the biggest emitters. The U.S. offshores a little bit of emissions, the EU offshores a bit more (about 18%). About 10% of China’s and India’s emissions represent offshoring, while the rest of Asia is basically neutral.

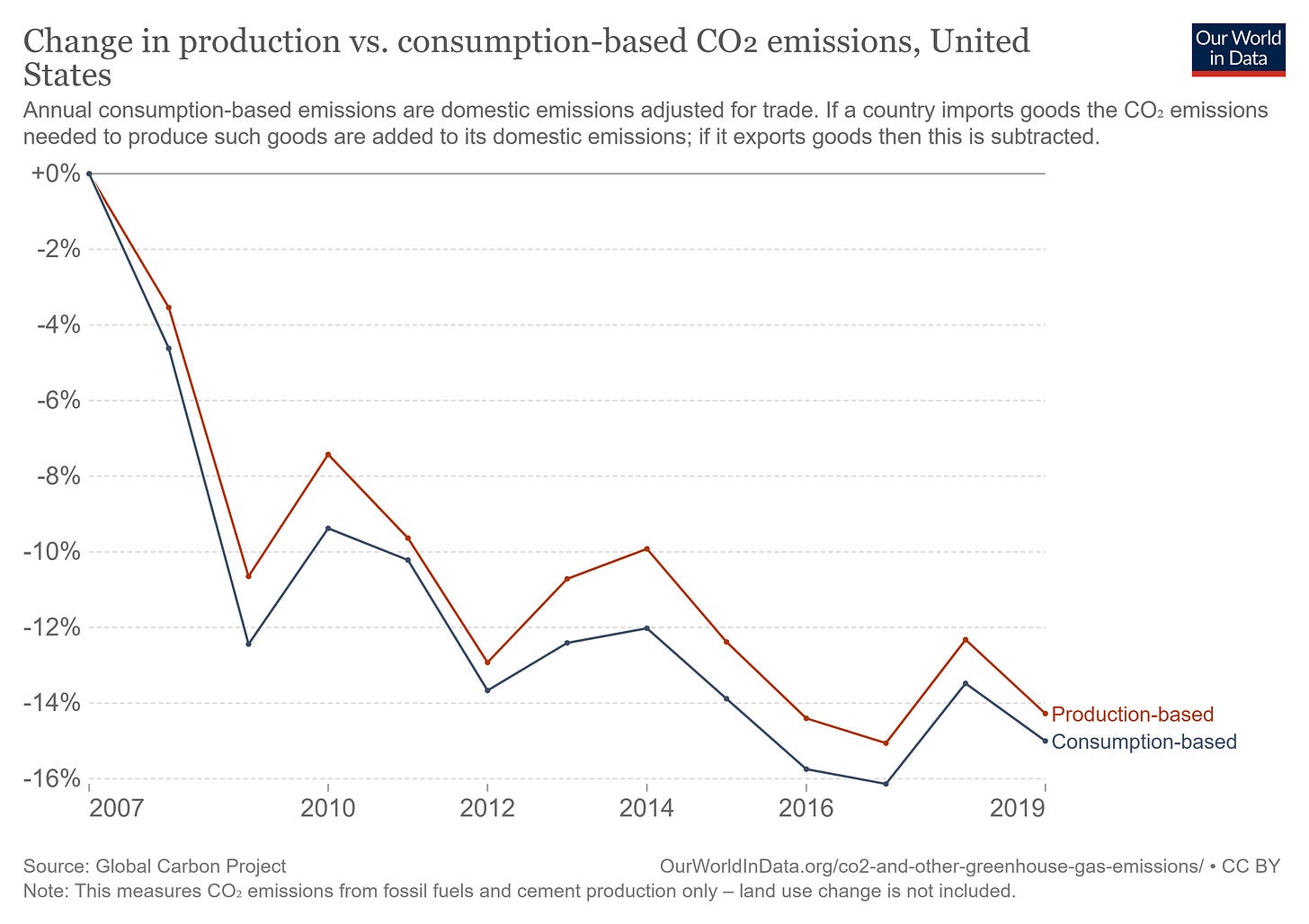

But when we look at the change in consumption-based emissions vs. production-based emissions, we see even more clearly that offshoring wasn’t the culprit. For example, U.S. emissions peaked in 2007 and have fallen since then. If this was due to offshoring, we’d expect to see consumption-based emissions fall by a lot less than production-based emissions. But in fact, consumption-based emissions actually fell by more!

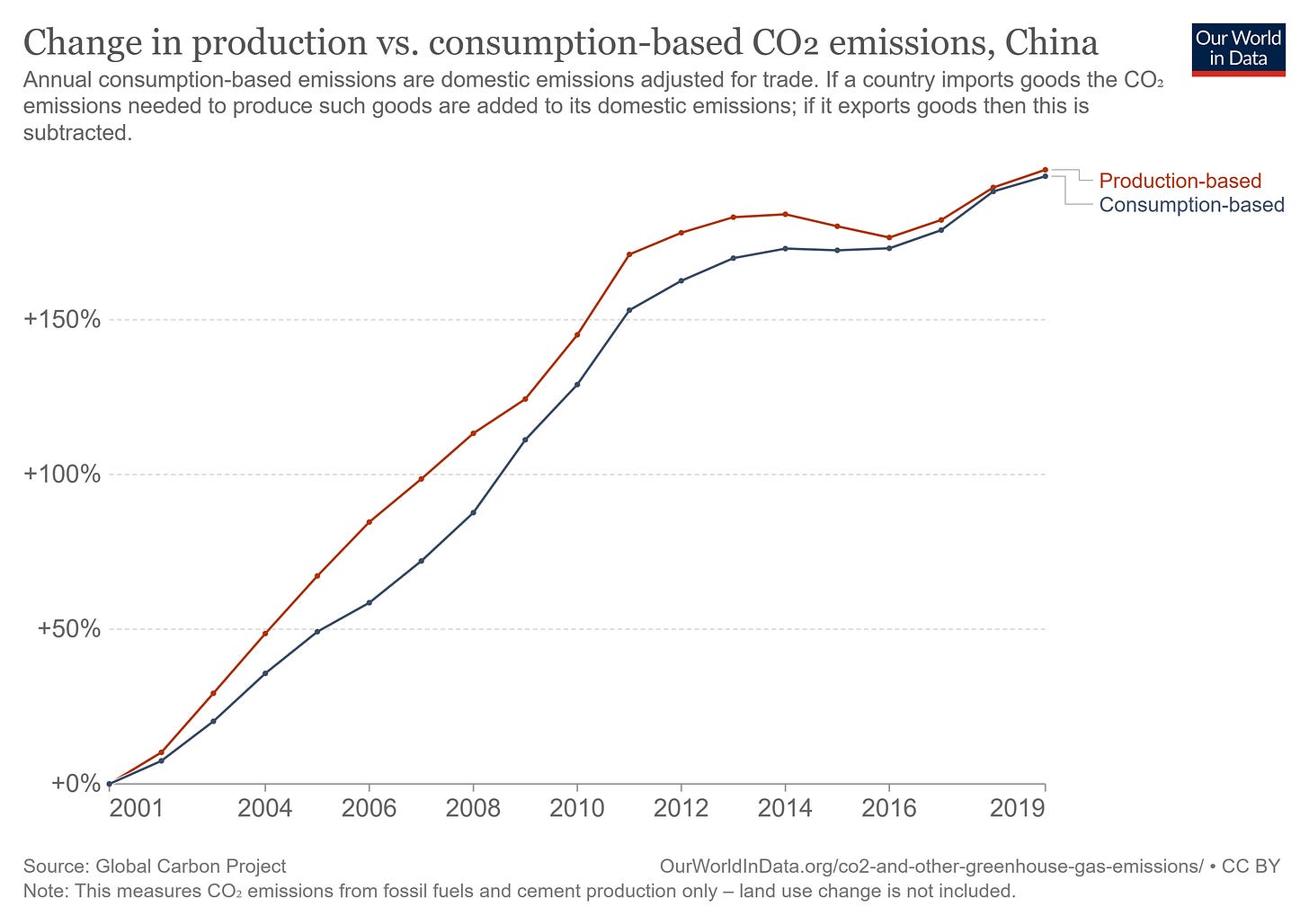

And if you look at the change since China joined the WTO in 2001 and major offshoring began, the difference is miniscule.

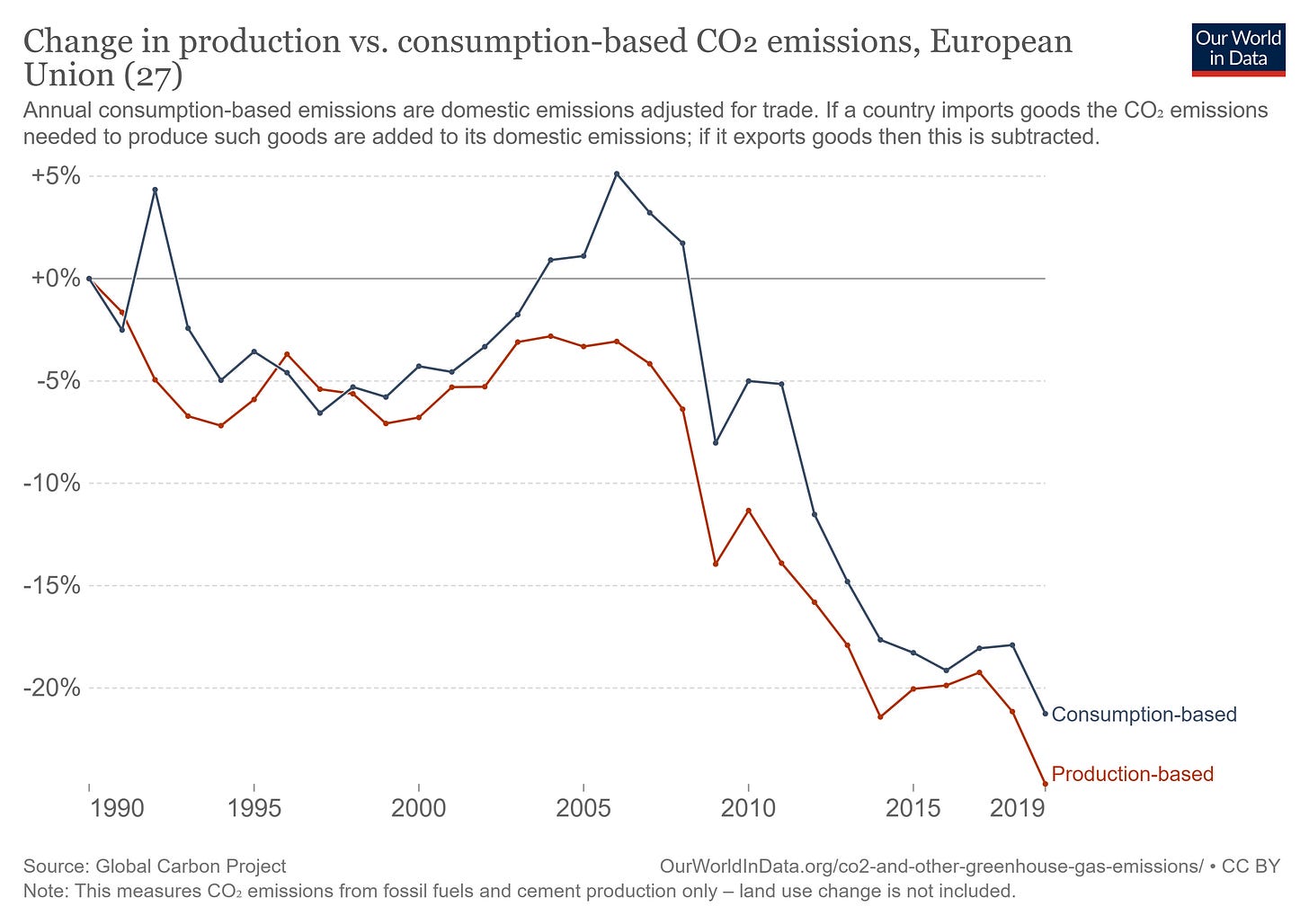

And for the EU, which has a much bigger gap between production-based and consumption-based emissions, the change since 1990 has been pretty equal:

Meanwhile, China’s production-based and consumption-based emissions have changed by pretty much the exact same amount since the country joined the WTO and offshoring kicked into high gear:

In other words, offshoring of emissions just isn’t that big of a deal. For most countries it just doesn’t change the story at all. For the EU it’s a somewhat bigger factor — about 18% of total emissions outsourced — but this amount hasn’t changed much in the last three decades, even as the EUs emissions have plummeted. As for the U.S., our emissions drop is more due to falling emissions consumption than to falling emissions production.

In other words, the idea that we cut our emissions by offshoring manufacturing to China is a total myth.

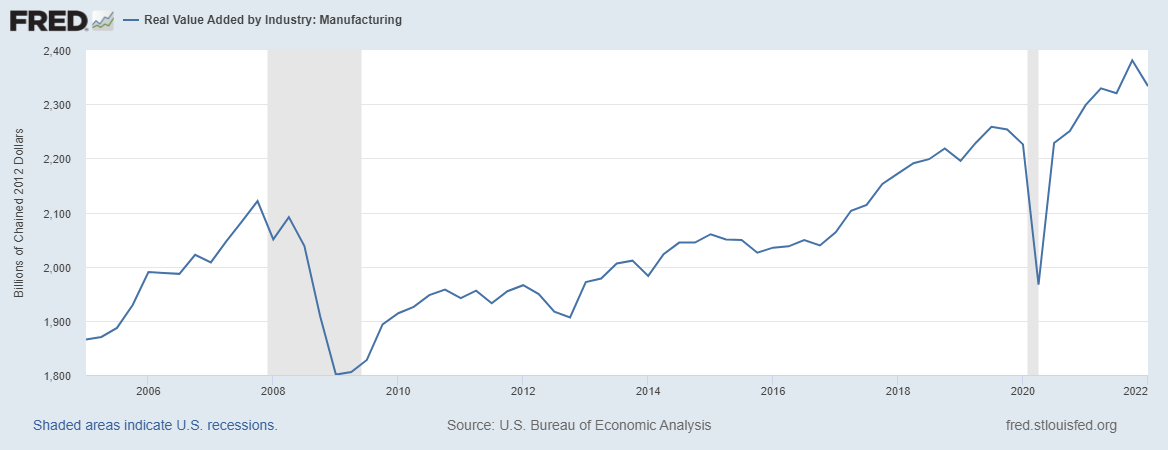

The notion that the U.S. offshored most of its manufacturing to China is very widespread. But this is also a myth. In terms of value added, the U.S. manufactures more now than we did in 2005:

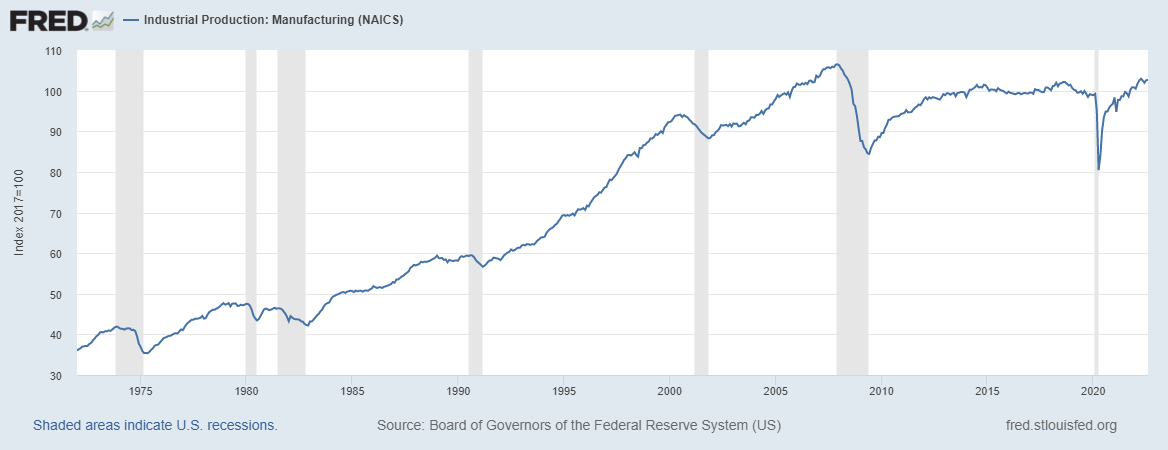

Industrial production in manufacturing — a slightly different measure — has been basically flat since the late 1990s. But still, that is not a decrease.

And when we look at the actual amount of what we import from China, it’s not actually that huge:

We imported about half a trillion dollars in goods from China in 2021. That’s about 18.6% of the total value added of the American manufacturing sector in that year.

And in fact, that’s not even an apples-to-apples comparison. As Michael Pettis and Matthew C. Klein would be quick to remind you, imports are not measured in terms of value-added. If the U.S. sells China some computer chips and screens and design instructions for $600, and a Chinese factory slaps them together into an iPhone and sells it back to a U.S. consumer for $800, it gets counted as $800 worth of imports, but the actual value added of the Chinese part of the manufacturing process is only $200.

In other words, U.S. imports from China are less than a fifth of the size of the U.S. manufacturing sector. That’s nothing to sneeze at, and it has certainly wreaked havoc on the lives of the American workers displaced by Chinese competition. But to think that we don’t make anything in America anymore is to blow the whole narrative wildly out of proportion.

One implication here is that the decrease in U.S. emissions isn’t due to offshoring of manufacturing. Of course, we shouldn’t pat ourselves on the back too hard here — we’ve still got a very long way to go. Also, much of our emissions reduction was based on switching from coal power to natural gas, which creates its own greenhouse problem via methane emissions that negate part of the improvement. (The Biden administration is tackling this problem.)

The bigger implication of this post is that the China emissions problem is not a product of offshoring. Which means America’s ability to force China to reduce emissions through policies like carbon tariffs is very limited. The massive amount of carbon emitted by China each year is not a problem made in America. It is a problem made in China, and one that only China can solve. And if China doesn’t choose to solve it, the world will indeed burn. That’s an uncomfortable fact, but it’s one we have to face.

Update: Here is a good thread on this topic. Basically, there was a little offshoring of emissions to China in the 2000s but it reversed.

So the “we offshored emissions to China” is just one more way that people’s minds get stuck in the past, as well as exaggerating minor trends.