In 1957, the executive committee of the American Economic Association (AEA) faced a moral dilemma. In three years’ time, the organization’s annual conference was scheduled to take place at the Roosevelt Hotel in New Orleans, Louisiana. With the recently decided case of Brown v. Board of Education, the Civil Rights Movement was in full swing. New Orleans, however, defiantly clung to racial segregation and the Jim Crow order of the old South.

With plans to be made and a hotel contract looming, the AEA’s leadership convened a meeting to discuss whether the organization could, in good conscience, host its conference at a segregated hotel in a segregated city. The posh Roosevelt Hotel – storied as a favorite drinking spot for Huey P. Long and generations of Louisiana’s political elite – was one such facility. It would hold out against racial integration until the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibited discrimination in public accommodations.

Facing a choice between proceeding with the contract or relocating to another city, the AEA’s executive committee decided to send a message. As per the meeting minutes, “it was the sense of this group that the Association will not meet in any hotel which is segregated with respect to meeting rooms, living accommodations, or dining facilities.” The committee assessed “the present situation in New Orleans,” after which its “Secretary was instructed to make alternative arrangements for 1960 as soon as possible.”

The AEA’s documents do not go into detail about the discussion behind their decision to relocate the conference. A recently discovered letter, however, reveals another layer to the story. Richard A. Musgrave, a member of the AEA executive committee, recounted the meeting’s decision to a colleague a few years later. Along with other AEA representatives, Musgrave protested “that we should not go there in view of discrimination.” He relayed the discussion that led to this decision:

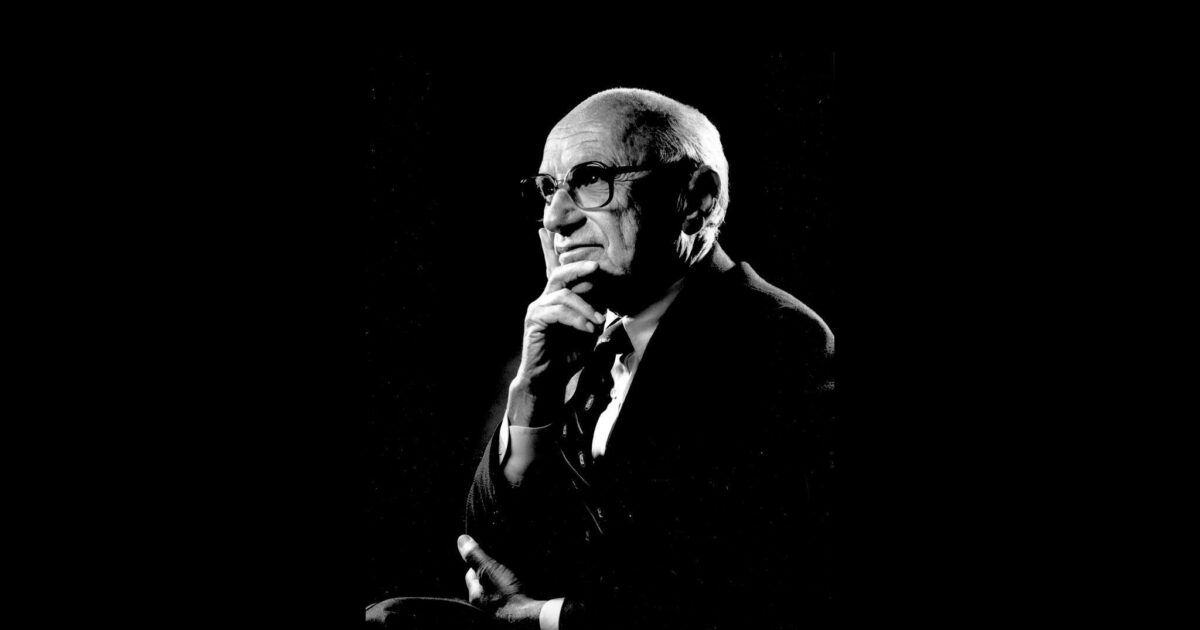

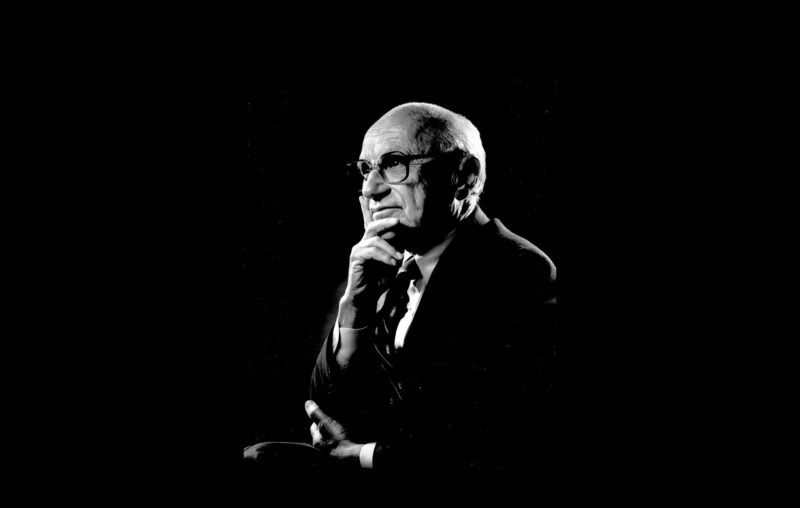

Milton Friedman added the point that – as an incentive matter – the hotel should be told that we would come (I think the date was ’62) if there was no discrimination. George Washington Bell, the secretary, was instructed to rearrange the schedule accordingly.

The AEA minutes record that the committee ordered the further delay of arrangements “until a later date in case the situation in New Orleans should change.” Per Friedman’s suggestion, the economists leveraged their contract to financially penalize the hotel’s practice of discriminating against non-white customers.

The AEA’s stance presented an opportunity for Friedman to act on a theory that his doctoral student, Gary Becker, proposed the same year in a dissertation written at the University of Chicago. Segregated businesses ultimately harmed themselves by denying their services to excluded racial groups, thereby losing them as customers. As Friedman later observed, economic decision-making could be used as a powerful weapon against discriminatory practices. In this case, if the Roosevelt Hotel would not allow black guests to stay on its premises, the economists would take their conference and its paying customers elsewhere.

Friedman would elaborate on this principle in his now-classic 1962 book, Capitalism and Freedom. As he wrote in that text, “It is often taken for granted that the person who discriminates against others because of their race, religion, color, or whatever, incurs no costs by doing so but simply imposes costs on others.” This view, Friedman continued, rested on an economic fallacy. “The man who objects to buying from or working alongside a Negro, for example, thereby limits his range of choice. He will generally have to pay a higher price for what he buys or receive a lower return for his work. Or, put the other way, those of us who regard color of skin or religion as irrelevant can buy some things more cheaply as a result.”

When Friedman advocated making the AEA’s hotel contract contingent upon their desegregating their facility, he aimed to drive home this point. If the Roosevelt Hotel would not integrate in time for the conference, it would not receive any business at all from the organization.

The AEA hotel episode reveals that Friedman’s arguments were not just hollow words in the service of free-market ideology – a charge often made against free-market economics by modern day detractors such as Nancy MacLean, who even falsely accuses Friedman of allying with segregationists to advance school vouchers.

As with many such smear campaigns, their history is not only erroneous – it is the exact opposite of reality. Friedman genuinely opposed racial segregation on moral and economic grounds, and his actions aligned with his rhetoric. When the time came to move on these beliefs in 1957, he chose to send an economic message to the offending business by diverting its customers elsewhere.