(Bloomberg Opinion) — Today, the Supreme Court is hearing two cases that are widely expected to overturn long-standing precedent and reject diversity as a rationale for considering race in university admissions. One case involves Harvard University, and the other the University of North Carolina. The ruling not only heralds major changes for higher education, but for private corporations as well.

The most obvious short-term consequence for employers is entry-level hiring. Elite employers recruit from elite universities. If those universities become less racially diverse, then the companies that recruit heavily from them — particularly those in tech, finance, law, accounting and consulting — may as well.

The more serious challenges for employers, however, go much deeper. The fundamental problem will be that the diversity objectives trumpeted by major corporations will no longer match an objective that has been blessed by the courts. Rather, racial diversity will be an objective the Supreme Court has rejected. That rejection will usher in a process of political and cultural conflict that companies will not be able to duck.

As the transition unfolds, whether gradually or quickly, every chief diversity officer in the country will need a new job title — and perhaps a new job. The pursuit of diversity, equity and inclusion will require rebranding and reimagining. There are also implications for the environmental, social and governance movement, as the S in ESG has come to include workplace diversity.

To see how and why this will happen, it’s worth starting by considering the legal technicalities of the two cases. In the case involving the University of North Carolina, the Supreme Court will likely say that under the Constitution, the meaning of “equal protection of the laws” prohibits any government entity from taking racial diversity into account. In the Harvard case, the court can be expected to hold that the anti-discrimination statute that covers private universities receiving federal funding — Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 — also disallows any form of race-based affirmative action or the express pursuit of racial diversity.

Workplace discrimination is governed by Title VII, a different section of the Civil Rights Act. So workplace diversity and workplace affirmative action won’t technically be before the court in the UNC and Harvard cases.

But that should not give solace to any employers hoping to stay out of the fray.

The language of Title VI, the discrimination statute that will be at issue in the Harvard case, is similar to the language of Title VII, the employment discrimination statute. If and when the court rules that the meaning of Title VI tracks the meaning of the equal protection clause of the Constitution, barring the consideration of racial diversity in admissions, it would be a logical conclusion for the courts to treat the language of Title VII as having a similar effect in the workplace.

In a 2020 decision, Bostock v. Clayton County, Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote for the court that Title VII should be read as prohibiting discrimination based on sexual orientation or transgender status. Liberals naturally embraced this progressive outcome. But as some scholars noted at the time, the literalism of the Bostock decision resonates with the idea of outlawing diversity in higher education: If an employer taking any account of sexual orientation or gender would count as discrimination “because of sex,” then taking any account of race would arguably count as discrimination “on the ground of race.”

It follows that a majority of the Supreme Court is very likely to hold — eventually — that Title VII outlaws the use of racial diversity as a lawful workplace objective. Even before that issue goes to the Supreme Court, conservative-leaning lower courts are likely to conclude that the Harvard-related holding sets a precedent for private employers, too — prohibiting the pursuit of race and sex diversity in hiring, promotion, or any other employment practice.

The only legal counterargument comes from a 1979 decision on private- employer affirmative action written by liberal lion Justice William Brennan. In it, the court held that Title VI (anti-discrimination by federally funded entities like universities) and Title VII (anti-discrimination in employment) need not be interpreted the same way. Although that case is still on the books, few court-watchers today would expect the current conservative majority to do anything but ignore or overturn it.

The upshot is that, once the court strikes down affirmative action in higher education, an employer who uses affirmative action to seek diversity along the lines of any category protected by Title VII workplace anti-discrimination law — which includes race, sex, religion and national origin — will be running the risk of being held liable for unlawful discrimination.

Of course, many corporations that trumpet workplace diversity as an objective do not acknowledge taking account of racial diversity in their hiring decisions. But if you were the general counsel of such a company, your first advice to your CEO in the aftermath of the Supreme Court’s affirmative action decision would be to reconsider even mentioning racial diversity as a corporate strategic objective.

The same conservative activists who have been suing universities for years will happily move on to suing corporations. And their objective was never merely to end affirmative action, but to strike a blow in the broader political and social struggle over the objective of diversity.

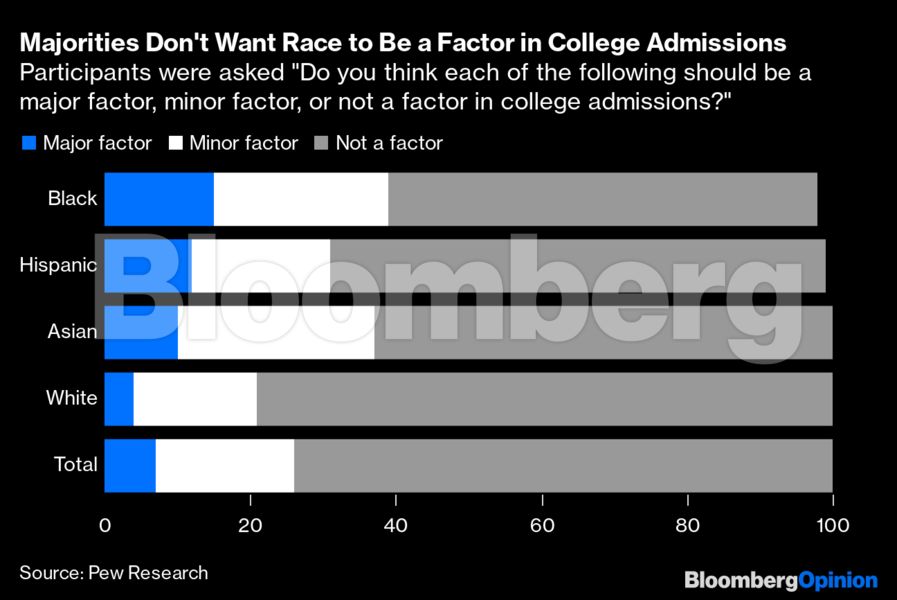

They seem to have the public on their side. A 2022 Pew study found that 74% of Americans believe race and sex should not be a factor in admissions. Majorities of White, Black, Latino and Asian-American people agree. Hence, the court’s decision is unlikely to trigger broad public backlash in the manner of the Dobbs decision, which overruled Roe v. Wade and allowed states to ban abortion — something most Americans believe should be legal.

Within some circles, however, there will be serious pushback against the court’s opinion. The ideal of diversity is simply too deeply entrenched for progressive CEOs to drop it from their agenda. Many corporations have come to believe, or at least profess, that more diverse companies achieve better financial results — despite making only partial progress on diversity themselves.

One potential middle option for corporations would be to try and maintain the ideal of diversity while steering clear of any concrete conduct that could be construed legally as using race or sex diversity as an objective in hiring and promotion.

The website of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission currently defines “workforce diversity” as “a business management concept under which employers voluntarily promote an inclusive workplace.” Under that definition, diversity might to a degree be allowed as a concept divorced from specific hiring decisions. In practice, however, it seems unlikely that corporations would — over the long run — double down on diversity once that concept has been repudiated by the Supreme Court.

The most likely result, I think, is that corporations will begin to back away from rhetoric that emphasizes the concept of diversity — as quickly and quietly as they can.

Consider the objective of more women’s representation on boards of directors and in C-suite and partnership level positions. In 2018, California went so far as to pass a law requiring female representation on boards of directors, although a state court judge struck down the law in May of 2022. Even voluntary efforts in this direction will now become legally suspect if they are expressed in terms of numeric targets.

Or consider policies that require interviewing nonwhite or female candidates for jobs, like the NFL’s Rooney rule. Such policies might well be struck down in court as unlawfully giving an employment advantage to their beneficiaries on the basis of race and sex.

As for ESG, an anti-diversity Supreme Court decision would come at what is already a potential inflection point. ESG is currently under attack by Republican state legislatures. So far, conservative activism has been mostly focused on the environmental component. But the social component will now be under attack, too.

The bottom line is that, once the Supreme Court has repudiated diversity in higher education, it will become gradually harder and harder for employers to invoke it as a key corporate value. Lawsuits or the fear of lawsuits will be one engine of eventual cultural transformation. Conservative activism will be another.

The process of change will not be simple or immediate. Diversity values have strong advocates. Companies will find themselves in the increasingly familiar territory of being caught between two sides in a culture war. Ultimately, however, the Supreme Court will make it difficult for the ideal of diversity to retain its sway in the C-suite.

More From This Writer at Bloomberg Opinion:

To contact the author of this story: Noah Feldman at [email protected]

© 2022 Bloomberg L.P.