John Burn-Murdoch’s

article

entitled “Britain’s winter of discontent is the inevitable result

of austerity” justifiably got considerable attention on social media, or at

least as much as any article published just before Christmas can. It

was noteworthy because it presented data on various measures of

public spending and real wages compared to the same data for similar

countries. In almost every case, spending and real wages in the UK

started in 2010 near the average of similar countries, but since then

has fallen to the bottom of that group.

The article closes

with the following paragraph:

“Lives lost,

earnings lost, years lost. Unlike Trussonomics, austerity is a slow

and silent killer. For the best part of twelve years, the

Conservatives sowed the seeds. This year they’re reaping the

harvest.”

The terrible impact

of austerity on public services, including the NHS and social care,

cannot be denied. Of course, it is frequently denied. The favourite

denial of the moment used by Conservative politicians is the

pandemic, but here the article has the perfect response. If you run a

public service like the NHS with barely the minimum resources required to

produce a normal service (or ‘efficiently’, as the government

might say), then there is no spare capacity to deal with emergencies

like the pandemic. The pandemic is not an excuse for the current

collapse in the NHS, but instead exposes for all to see the harm that

was being done by underfunding over the previous decade.

Of course the signs

that the NHS was being steadily deprived of funding was evident well

before the pandemic hit, for those that bothered to look at NHS

performance data. Waiting times for operations or emergency care were

steadily rising. But unfortunately most of the time many prominent

political journalists did not look at the data, but instead parroted

the government line that the NHS was ‘protected’ from cuts.

In doing this these

journalists played their part in being responsible for one of the

most insidious deceits of the 2010s. I wrote

about it back in 2015. The first deceit is in the

definition of protected. A natural way of thinking about protection

would be to keep NHS spending constant as a share of GDP, or at least

constant in terms of spending per head. The way the government

defined protection was constant in real terms, which with an

expanding population meant less spending per head, and a shrinking

share of GDP. The second deceit was to ignore the many reasons why

this natural definition is not a good one. NHS spending has increased

as a share of GDP since the 1950s, just as health spending in most

countries has increased, because of an ageing population and many

other good reasons. Health spending therefore needed to increase as a share of

GDP just to maintain existing services at a reasonable standard. In

most of the 2010s the government reduced rather than increased health

spending as a share of GDP, so the service steadily deteriorated.

Were the many

political correspondents who repeated the lie in the 2010s that NHS

spending was being protected aware of these points? If not, then they

were pretty bad at their job using any standard definition of

journalism. The lie that NHS spending was being protected was

repeated so often as fact that voters naturally wondered why their

access to the health service seemed to be getting worse. If it wasn’t

lack of money, some reasoned, it must be because of the ‘waves of

immigration’ they kept reading about in newspapers. Government

ministers said much the same: another lie that ignored the fact that

the more people who work the greater the taxes available to fund

additional spending. For this and more

general reasons, it is not hard to understand why

austerity was followed by the political populism of Brexit.

Public discussion of

public spending cuts since 2010 is littered with lies and

misdirection of the ‘protected’ kind. When I last took a

comprehensive look at public spending data two

years ago, Johnson was promoting the idea that

austerity was at an end. What this meant in practice was some small increases in spending in a few areas. So

Johnson brought the policy of constantly cutting all areas of public

spending to an end, but if you talk about an end to austerity it

sounds like you are completely reversing what had been done since

2010. It was a classic piece of misdirection, again repeated in much

of the media. In reality the likely increase in health spending

between 18/19 and 22/23 only matches

the increases of the Thatcher/Major administrations,

and remains below the 55-78 average.

Johnson encouraged

this misapprehension with talk of 40 new hospitals – just one more

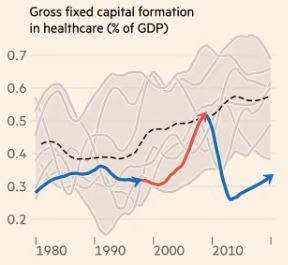

lie. The reality of investment in the NHS since 2010 is clearly shown

in one chart from the Burn-Murdoch article. The grey area includes

all the data from comparator countries, and the dotted line is their

average.

UK investment in healthcare, which the last Labour government had increased to around the average in comparator countries, has since 2010 been cut to well below that in any of these other countries. It is the consequent lack of capacity (beds, equipment etc) that is behind a large part of the current NHS crisis.

The FT article shows

a similar pattern for UK real wages, in PPP terms, compared to

comparator countries. Although it was less dramatic than in health

spending, real wages slightly improved compared to similar countries

under Labour, but since 2010 the UK has been heading towards the

bottom of this league. This reflects general trends in economic performance since 2010, as

I have often noted. Those trying to portray events

since 2010 as just the latest chapter in an uninterrupted century of

UK economic decline are also guilty ignoring the data, as Adam Tooze has

recently

emphasised.

Are the declines in

UK health spending and real wages relative to other countries

connected, as the closing paragraph quoted above of the Burn-Murdoch article

suggests? To be fair the case is not made, and because austerity

after 2020 happened in most similar countries to varying degrees the

connection is not obvious. I think it is highly likely that UK real

wages would be significantly higher today if Osborne had not cut

public investment in the middle of a recession, but the same would be

true in other countries that also undertook spending cuts after 2010.

However there is a

similarity between developments in UK real wages and health spending which Burn-Murdoch does point out. The stagnation in real wages has

been evident for a decade but it takes a cost of living crisis

created by high food and energy prices to make that decline evident

to those who don’t look at data, just as the pandemic has exposed

the underlying fragility in the NHS. Once again the media has played

a large part in hiding this reality until recently, with talk among

Conservative politicians of a ‘strong economy’ going unchallenged

for years when the opposite has been true.

In both the case of

public spending and real wages, large parts of the media were

complicit in hiding the truth from the public by repeating or not

challenging the lies coming from the government. I think a large part of this stems from adopting the view, as much of the media did from 2009 onwards, that reducing the deficit was the primary and most urgent goal of macroeconomic policy. Once you accept that myth, which had little to do with macroeconomic reality, then it seems pointless reporting about the consequent declines in public services, and the economy must be strong because the deficit was coming down. It was why I had no

hesitation in calling my

book “The Lies We Were Told”.

But I want to end on

a more positive note. The best journalists have always made sure what

they wrote or said was firmly based on facts, and I think we are now

seeing more prominence being given to data-based journalism,

exemplified in the work of John Burn-Murdoch at the FT and

journalists like Ben Chu on Newsnight and Ed Conway on Sky.

For much political

and economic discussion, being able to access and understand data is

at least as important as the ability to write well. There is a phrase

about damn lies and statistics, but the best way to call out

misleading statistics is to just present the data. [1] Political

journalists in particular need to write less about who is up and who

is down, and instead to start filling their column inches with charts

of data. If that had happened more often in the past, then it

wouldn’t have required a pandemic or cost of living crisis to

reveal to everyone what was happening to the health

service and real wages.

[1] An anecdote does

not prove anything, but I cannot resist this one as a footnote.

During the flooding in late 2013, I wrote a few posts (e.g. here)

on its links with austerity. At the time Cameron was claiming that

spending on flood prevention had not been cut, and the media was

doing its ‘he said, they said’ thing. My articles were based on

official data that clearly showed spending on flood prevention had

been sharply cut as part of austerity. Yet to my knowledge no one in

the media showed that (publicly available) data. That is called

hiding the truth.

As a result of these

posts, two years later when further floods occurred Newsnight

contacted me thinking I was an expert on flood prevention. I’m not,

but I implored them to just show the data on which my articles had

been based, which I knew would be more powerful than anything said in

a talking heads discussion. They

did, and this made impossible any attempt to deny spending on flood

prevention had been cut under austerity.