In a Liberty Street Economics post that appeared yesterday, we described the mechanics of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet “runoff” when newly issued Treasury securities are purchased by banks and money market funds (MMFs). The same mechanics would largely hold true when mortgage-backed securities (MBS) are purchased by banks. In this post, we show what happens when newly issued Treasury securities are purchased by levered nonbank financial institutions (NBFIs)—such as hedge funds or nonbank dealers—and by households.

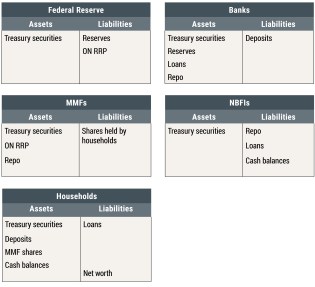

Simplified Balance Sheets

In the exhibit below, we describe the simplified balance sheets for the Fed, banks, MMFs, NBFIs, and households. We only show the balance sheet items that are essential for understanding the mechanics related to the Fed’s actions.

Initial Conditions

- On the Fed’s balance sheet, the asset side contains Treasury securities; the liability side contains reserves held by banks and funds invested by MMFs in the Overnight Reverse Repurchase Agreement (ON RRP) facility.

- On banks’ balance sheet, the asset side contains Treasury securities, reserves held at the Fed, loans, and (reverse) repurchase agreements (repos) with NBFIs; the liability side contains deposits from households.

- On MMFs’ balance sheet, the asset side contains Treasury securities, investments in the ON RRP facility, and (reverse) repos with NBFIs; the liability side contains MMF shares held by households. In contrast to banks, MMFs cannot hold balances in a Fed account. Note that in contrast to our previous post, for simplicity’s sake, MMFs do not hold bank deposits (indeed, as we remarked in our previous post, government MMFs, the largest segment of the MMF industry, are not allowed to hold deposits).

- On NBFIs’ balance sheet, the asset side contains Treasury securities; the liability side contains repos with banks and MMFs, loans, and cash balances from households. Note that we focus on levered NBFIs—that is, NBFIs that finance a substantial proportion of their assets through debt (for example, by borrowing in the repo market); other NBFIs (such as open-ended mutual funds or pension funds) are un-levered and they fund most of their asset purchases with cash balances from households.

- Finally, on households’ balance sheet, the asset side contains Treasury securities, deposits at banks, MMF shares, and cash balances at NBFIs. The liability side of the balance sheet contains loans and the difference between assets and liabilities is households’ net worth.

We assume that $1 worth of Treasury securities held by the Fed matures and the Treasury issues $1 worth of new securities. In this post, the new securities are purchased by NBFIs or households and the Treasury uses the proceeds of the newly issued debt to meet the Fed’s redemptions. For this reason, the Treasury’s balance sheet remains unchanged, and therefore, we can ignore it.

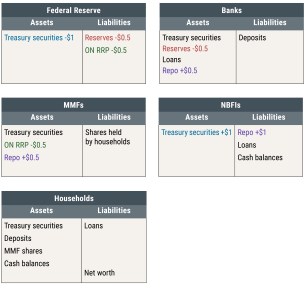

Levered NBFIs Purchase the Newly Issued Securities

We first consider the case in which levered NBFIs purchase the newly issued securities (see exhibit below).

Levered NBFIs Purchase New Treasury Securities

Several transactions happen at the same time:

- NBFIs finance the purchase of the new securities through repos from banks ($0.5) and MMFs ($0.5), with the newly issued securities as collateral. The size of NBFIs’ balance sheet increases by $1: on the asset side, they hold more Treasury securities; on the liability side, their repos have increased by the same amount.

- Banks lend to NBFIs through (reverse) repo contracts. The size of banks’ balance sheet is unchanged, but the composition of bank assets is changed (lower reserves, higher repo lending).

- Similarly, MMFs lend to NBFIs through (reverse) repo contracts. The size of MMFs’ balance sheet is unchanged, but the composition of MMF assets is changed (lower ON RRP balances, higher repo lending). Note that, similarly to our previous post, MMFs could also lend to NBFIs by using their deposits with banks (not shown in the exhibits), in which case the size of banks’ balance sheet would shrink.

- At the end of this process, the size of the Fed’s balance sheet has decreased. The asset side contains fewer Treasury securities ($1); on the liability side, there is a reduction of reserves held by banks ($0.5) and ON RRP take-up ($0.5).

In this example, NBFIs are the only private-sector entities to increase their security holdings, and since we are considering levered NBFIs, they fund the purchases solely through borrowing in the repo market; this implies that as a result of the runoff, leverage in the financial system has increased. As we mentioned above, there are other NBFIs (such as open-ended mutual funds or pension funds) that are un-levered and that would fund their purchase of Treasury securities by either selling other assets or increasing the amount of cash balances they receive from households.

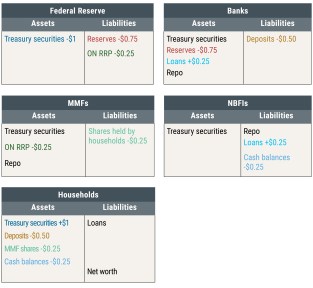

Households Purchase the Newly Issued Securities

We now consider the case in which households purchase the newly issued securities (see exhibit below).

Households Purchase New Treasury Securities

Households have different levels of wealth. It is likely that not all households invest in the same set of financial assets; for instance, while many households may have their savings in bank deposits and MMFs, only wealthier households are likely to invest in levered NBFIs, like hedge funds.

- As households are heterogeneous and likely keep their savings in different types of assets, in our example we assume that in the aggregate they fund the purchase of new Treasury securities by reducing their deposits with banks ($0.5), their holdings of MMF shares ($0.25), and their cash balances with NBFIs ($0.25). The size of households’ balance sheet is unchanged, but the composition of household assets is changed (increased holdings of Treasury securities; lower deposits at banks, lower holdings of MMF shares, and lower balances placed in cash accounts with NBFIs).

- MMFs react to the reduction of households’ investment by reducing their ON RRP take-up. MMFs’ balance sheet shrinks; assets are lower by $0.25 (lower ON RRP take-up) and so are liabilities (fewer shares).

- Levered NBFIs make up for the reduction of households’ cash balances ($0.25) by borrowing from banks. Note that although NBFIs could also borrow from MMFs (as in the previous case), for simplicity’s sake we assume that they do not do so. The size of NBFIs’ balance sheet is unchanged, but the composition of NBFIs’ liabilities is changed (lower cash balances, higher loans from banks).

- Banks reduce their reserves ($0.5) in response to the decline in households’ deposits. Banks also issue loans to NBFIs ($0.25) that cover the loss in funding of NFBIs by households. Banks fund the loans through a further $0.25 reduction in the reserves they hold. The size of banks’ balance sheet only goes down by $0.5, reflecting the reduction in households’ deposits.

- At the end of this process, the Fed’s balance sheet shows a reduction of Treasury securities by $1 on the asset side, accompanied by a reduction in reserves by $0.75 and in ON RRP take-up by $0.25.

This example illustrates the potential for the Fed’s balance sheet reduction to affect several different markets and institutions.

Conclusions

The actual evolution of private-sector balance sheets could involve adjustments similar to those outlined in the various scenarios described in our previous post on balance sheet runoff and in this one. These scenarios indicate that the adjustments in private-sector balance sheets can be quite complex, involving flows across markets and institutions that exceed the dollar value of the net increase in securities holdings by the private sector. Also, whether the adjustment on the Fed’s balance sheet happens through a reduction of reserves or of ON RRP investment depends on the type of securities that the Treasury issues (that is, whether MMFs can hold these securities), as well as on the relative return on different types of money market instruments.

Marco Cipriani is an assistant vice president in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

James Clouse is a deputy director in the Division of Monetary Affairs at the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Lorie Logan is an executive vice president in the Bank’s Markets Group.

Antoine Martin is a senior vice president in the Bank’s Research and Statistics Group.

Will Riordan is an assistant vice president in the Bank’s Markets Group.

How to cite this post:

Marco Cipriani, James Clouse, Lorie Logan, Antoine Martin, and Will Riordan, “The Fed’s Balance Sheet Runoff: The Role of Levered NBFIs and Households,” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Liberty Street Economics, April 12, 2022, https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2022/04/the-feds-balance-sheet-runoff-the-role-of-levered-nbfis-and-households/.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this post are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.