Many central bank officials have been trying all sorts of conditioning narratives to convince us that their interest rate hikes have been justified. Now they are actually defying the information presented in the official data to simply make things up. Last Wednesday (May 17, 2023), the Bank of England governor gave a speech to the British Chamber of Commerce – Getting inflation back to the 2% target − speech by Andrew Bailey. It came after the Bank raised the bank rate by a further 25 points to 4.5 per cent the week before. In that speech, he admitted inflation was declining and the main supply-side drivers were abating. But he said the rate rises were justified and unemployment had to rise because there was now persistent inflationary pressures coming from a “wage-price spiral”. The problem with this claim is that there is no data to support it.

There is a wage-price spiral in the UK – pity I cannot see it.

The Bank of England governor told the Chamber of Commerce gathering that Britain was in an “extraordinary situation” (Covid, etc) and like all nations had been hit with “a series of big supply shocks”, including the decline in output as Covid restricted activity and households shifted spending from services (which were constrained) to goods.

This shift in 2020 and 2021 prompted some economists to claim that inflation was a demand-side phenomenon, which required hard government net spending cuts and interest rate rises.

However, my position all along is that it is a rather bizarre construction of events to consider the appropriate remedy is to stifle demand – which has the result that unemployment rises – when the supply contraction was temporary and would resolve in due course.

The last thing we should be doing is creating unemployment because when governments engage in demand suppression either directly through fiscal policy or indirectly through monetary policy, unemployment tends to rise quickly and fall slowly, leaving a trail of personal and community hardship and disadvantage behind it.

The correct response was the one taken by the Japanese government and monetary authorities.

Japan was subjected to the same global supply constraints which pushed up costs but the central bank governor told us that they had formed the view that the supply pressures were transitory and didn’t justify an all out attack via interest rate increases which would endanger the nation’s low unemployment.

The Cabinet agreed and used fiscal policy to provide some cash support to households to ease the (temporary) cost of living pressures and to businesses as part of a deal to suppress profit margins and keep the price rises down.

The result of this approach has seen inflation dropping well below the levels in other advanced nations and unemployment remain very low.

By any measure a success.

And it is a wonder that the mainstream press ignores the ‘experiment’ and just mimics the narratives presented by the other central bank governors.

I even heard and economist telling the national ABC radio the other day in a key feature on the economy that ‘central banks are increasing rates everywhere’.

Which was a lie and the journalist failed to pick her up on it.

In his speech to the Chamber of Commerce, the Bank of England governor acknowledged that:

… global supply pressures have eased.

Significantly to say the least.

He also indicated that the rising energy costs as a result of the Ukraine situation “will also now reverse”.

So then what is driving inflationary pressures in the UK?

Well he claims that the third:

… supply shock has been a domestic one …

And there we learn that Covid led to a sharp fall in the “size of the workforce” through inactivity – which mostly is because of illness.

The most recent labour market data from the Office of National Statistics (released May 16, 2023) – Labour market overview, UK: May 2023 – is quite shocking in its revelations.

1. “those inactive because of long-term sickness increased to a record high.”

2. “2.55 million people were not able to work in the three months to March, which is over 6% of the country’s working population. That was up nearly 100,000 on the previous quarter.” (Source).

3. “the pandemic is likely to be one of the main causes for the increase in the number of long-term sick over the past three years or so, including those suffering from long COVID symptoms such as post-viral fatigue.”

4. “This is now comfortably the largest number of people out of the labor market due to long-term health problems that we have ever seen”.

The reality is that our nations will endure a large (and growing) cohort of workers with permanent disability as a result of Covid infections.

The cavalier way in which we are now in full stage denial of this problem is astounding.

But the governor is also keen to note that the workforce shortages that became acute during the early years of Covid are “reversing somewhat”.

Then there are “food prices”, in part arising from the “disruptions to Ukraine’s supply of agricultural products to the global market”, which have been a major contributor to British inflation in the last year (“the annual CPI inflation for food and non-alcoholic beverages in the United Kingdom has risen from 5.9% in March 2022 to 19.1% in the latest March 2023 numbers”).

All of these points are incontestable really.

As is his observation that inflation hurts “the least well-off harder” because they spend more of their income on the items that have inflated the most.

But there is no retreat from his view that the interest rate rises were essential – even if they hurt the low-income families the most – “to bring inflation down”.

He noted that the “real income” losses that arise from rising imported raw materials or products cannot be solved by monetary policy.

So why did they raise rates?

His simple explanation is that the Bank had:

… to take action to ensure that inflation falls as the external shocks abate – that inflationary impulses from these external sources do not cause persistent ‘second-round’ effects on domestic wage and price setting that could hold inflation up for longer. That is why we have increased Bank Rate by nearly 4½ percentage points from December 2021, from 0.1% then to 4.5% now.

Ah, the wage-price spiral argument – finally.

The ‘dreaded second-round effects’.

He claimed that even though inflation is falling as the supply drivers abate, there is a dangerous persistence setting in due to these “second-round effects”.

What are they?

Well, he said the Bank had desired a rise in unemployment (a “shallow but long recession”) the problem is that the rise has been “happening at a slower pace than we expected in February”.

In other words, they haven’t yet achieved their goal of pushing tens of thousands of workers into joblessness.

As a result, he claimed that the MPC:

… continues to judge that the risks to inflation are skewed significantly to the upside, primarily reflecting the possibility of more persistence in domestic wage and price setting.

So we have moved from narratives, such as those pushed by the Reserve Bank of Australia governor that they ‘fear’ a wage-price spiral, to more definitive claims that the inflation is now being driven by the presence and operation of such a spiral.

Which has become their justification for the on-going interest rate hikes.

The evidence?

Central bank governors like to mention their private briefings with the business sector and have claimed in those meetings they learned about higher wages growth.

Initially, we couldn’t refute the claims because we didn’t have enough official data, which would have eventually revealed the growing wage pressures had they been occuring.

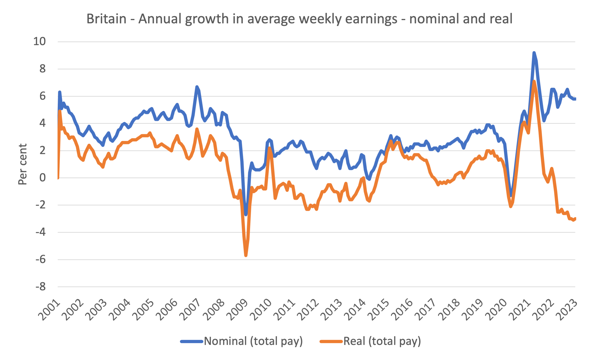

But now more than 18 months into the rising inflationary pressures, the official data for Britain is still recording real wage cuts, of a systematic nature, which rules out any wage-price spiral dynamics.

If we observed a leapfrogging pattern – where a large nominal wage increase resulted in real wage increases was followed by a surge in inflation next quarter and so on – then we might conclude that the distributional struggle between labour and capital as to who would take the losses in real income as a result of the imported cost increases.

But when the real wage cuts are systematic then it is much harder to construct the problem as an interactive wage-price spiral.

The latest ONS wages data (released May 16, 2023) – Average weekly earnings in Great Britain: May 2023 – the day before the governor made his speech shows that:

Growth in employees’ average total pay (including bonuses) was 5.8% and growth in regular pay (excluding bonuses) was 6.7% in January to March 2023.

However, and this is the significant point:

Growth in total and regular pay fell in real terms (adjusted for inflation) on the year in January to March 2023, by 3.0% for total pay and 2.0% for regular pay; for real total pay a similar fall was seen in the previous three-month period and remains among the largest falls in growth since comparable records began in 2001.

The following graph shows the annual growth in nominal and real average weekly earnings (total pay) from the March-quarter 2001 to the March-quarter 2023 (latest data).

Note the dynamics.

The initial recovery in earnings from the lockdown period soon gave way to a systematic loss of purchasing power as the supply-side inflation powered off and nominal wages failed to catch up.

Since mid-2022, workers have endured real wage cuts each quarter.

Even the nominal wage inflation has been fairly stable since the end of last year.

The last two quarters have seen no acceleration in nominal wages.

Conclusion

Remember when the inflation was just taking off, the Bank of England governor told British workers that they had to take a pay cut or else he would make more of them unemployed than he was already planning to do via the interest rate hikes.

Well, they did take that pay cut, albeit in an involuntary way, and real wages have fallen systematically over the last year.

Now the same governor is blaming workers for creating a persistent second-round wage-price spiral by refusing to accept an even larger real wage cut.

I know all the economic models of wage-price spirals – mainstream and others – and none would suggest that such a dynamic could really occur and persist when there are systematic real wage losses being incurred.

There is no hint of a leap-frogging pattern in Britain.

This is another central bank governor that needs to be rendered unemployed.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2023 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.