The world’s most-watched central banks are finally stamping down on a surge in inflation. But this week it became clear that they know this comes at a cost.

From the UK, where the Bank of England raised interest rates for the fifth time in as many meetings, to Switzerland, which bumped up rates for the first time since 2007, policymakers in almost every major economy are turning off the stimulus taps, spooked by inflation that many initially dismissed as fleeting.

But for the big two in particular — the US Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank — the prospect of sharply higher rates brings awkward trade-offs. For the Fed, that is in employment, which is at risk as it pursues the most aggressive campaign to tighten monetary policy since the 1980s. The ECB, meanwhile, this week scrambled an emergency meeting and said it would speed up work on a new plan to avoid splintering in the eurozone — an acknowledgment of the risk that Southern Europe and Italy in particular could plunge in to crisis.

Most central banks in developed countries have a mandate to keep inflation under 2 per cent. But the roaring consumer demand and supply-chain crunch stemming from the Covid reopening, combined with the energy price spiral generated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, has made this impossible.

At first, policymakers considered inflation spikes to be transitory. But now, US inflation is running at an annual pace of 8.6 per cent, the fastest in more than 40 years. For the eurozone, it is 8.1 per cent and in the UK, 7.8 per cent. Central banks are being forced to act far more aggressively.

Investors and economists think policymakers will struggle to avoid imposing pain, from rising unemployment to economic stagnation. Central banks have moved “from whatever it takes to whatever it breaks”, says Frederik Ducrozet, head of macroeconomic research at Pictet Wealth Management.

The Fed faces reality

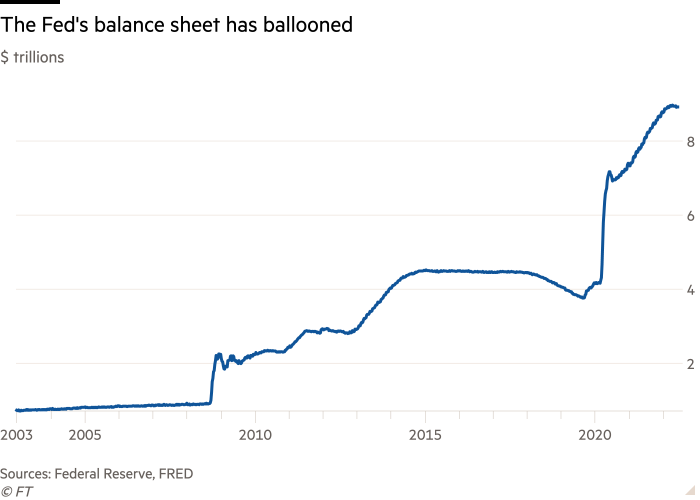

Above all, the US Federal Reserve this week dramatically scaled up its response. It has been raising rates since March, but on Wednesday it delivered its first 0.75 percentage point rate rise since 1994. It also set the stage for much tighter monetary policy in short order. Officials project rates to rise to 3.8 per cent in 2023, with most of the increases slated for this year. They now hover between 1.50 per cent and 1.75 per cent.

The Fed knows this might hurt, judging from the statement accompanying its rate decision. Just last month, it said it thought that as it tightens monetary policy, inflation will fall back to its 2 per cent target and the labour market will “remain strong.” This time around, it scrubbed that line on jobs, affirming instead its commitment to succeeding on the inflation front.

To those familiar with reading the runes of the Fed, this matters. “This was not unintentional,” says Tim Duy, chief US economist at SGH Macro Advisors. “The Fed knows that it is no longer possible in the near term to guarantee” both stable prices and maximum employment.

3.6%

The US jobless rate, which is close to a historical low. Some 390,000 jobs were created in May alone

The prospect of a recession in the US and elsewhere has already sent financial markets swooning. US stocks have posted the worst start to any year since the 1960s, declines that have accelerated since the latest central bank pronouncements. Government bonds, meanwhile, have flipped around violently under the competing forces of recession fears and rising benchmark rates.

“The big fear is that central banks can no longer afford to care about economic growth, because inflation is going to be so hard to bring down,” says Karen Ward, chief market strategist for Europe at JPMorgan Asset Management. “That’s why you are getting this sea of red in markets.”

At first glance, fears of a US recession might appear misplaced. The economy roared back from Covid lockdowns. The labour market is robust, with vigorous demand for new hires fuelling a healthy pace of monthly jobs. Almost 400,000 new positions were created in May alone, and the unemployment rate now hovers at a historically low 3.6 per cent.

But raging inflation puts these gains in jeopardy, economists warn. As the Fed raises its benchmark policy rate, borrowing for consumers and businesses becomes more costly, crimping demand for big-ticket purchases like homes and cars and forcing companies to cut back on expansion plans or investments that would have fuelled hiring.

“We don’t have in history the precedent of raising the federal funds rate by that much without a recession,” says Vincent Reinhart, who worked at the US central bank for more than 20 years and is now chief economist at the Dreyfus and Mellon units of BNY Mellon Investment Management.

The Fed says a sharp contraction is not inevitable, but confidence in that call appears to be ebbing. While Fed chair Jay Powell this week said the central bank was not trying to induce a recession, he admitted that it had become “more challenging” to achieve a so-called soft landing. “It is not going to be easy,” he said on Wednesday. “It’s going to depend to some extent on factors we don’t control.”

That more pessimistic stance and the Fed’s aggression against rising prices has compelled many economists to pull forward their forecasts for an economic downturn, an outcome for the central bank that Steven Blitz, chief US economist at TS Lombard, says was a “moment of their own design” by moving too slowly last year to take action against a mounting inflation problem. Most officials now expect some rate cuts in 2024.

“Because of their inept handling of monetary policy last year, and their own belief in a fairytale world as opposed to seeing what was really going on, they put the US economy and markets in this position that they now have to unwind,” he says. “They were wrong and the US economy is going to have to pay the price.”

Whatever it takes?

The ECB has a challenge of a more existential kind.

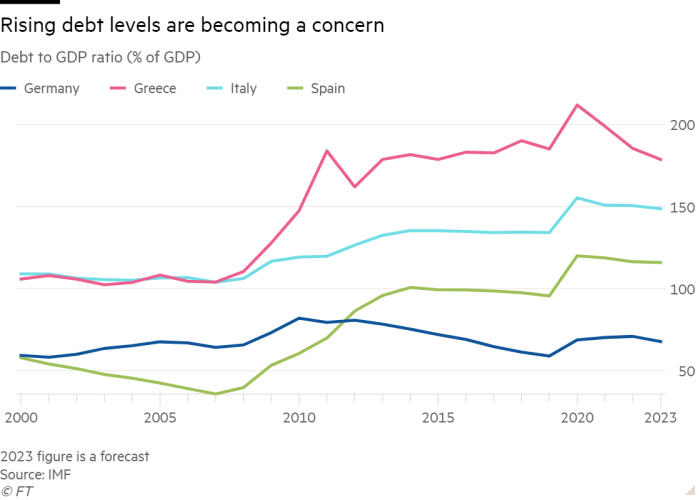

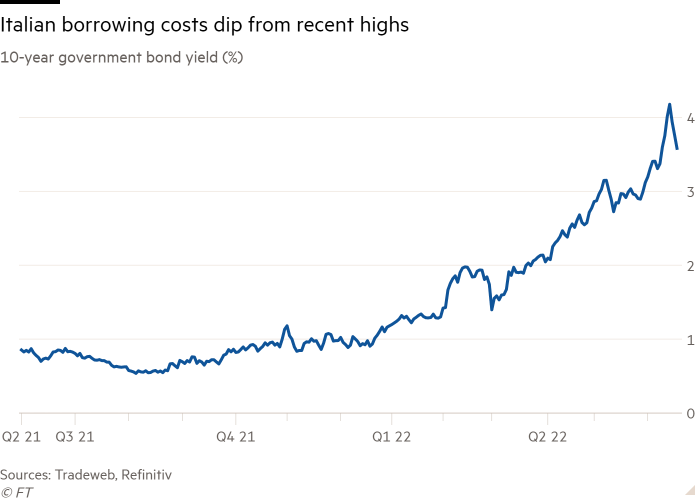

This week it called an emergency meeting just days after its president Christine Lagarde announced a plan to raise rates and to stop buying more bonds in July. That plan makes sense in the context of record-breaking inflation. But it had the awkward effect of hammering government bonds issued by Italy, historically a big borrower and spender. Italy’s 10-year bond yield rose to an eight-year high above 4 per cent and its gap in yields from Germany hit 2.5 percentage points, its highest level since the pandemic hit two years ago.

This outsized pressure on individual member states’ bonds makes it hard for the ECB to apply its monetary policy evenly across the 19-state eurozone, risking the “fragmentation” between nations that ballooned a decade ago in the debt crisis. Faced with early signs of a potential rerun, the ECB felt it had to act.

Italian central bank governor Ignazio Visco said this week that its emergency meeting did not signal panic. But he also said that any increase in Italian yields beyond 2 percentage points above Germany’s created “very serious problems” for the transmission of monetary policy.

3.6%

Italy’s 10-year bond yield. It has to refinance a borrowing load of around 150 per cent of gross domestic product.

The result of the meeting was a commitment to speed up work on a new “anti-fragmentation” tool — but with little detail on how it would work — while also reinvesting maturing bonds flexibly to tame bond market jitters.

Some think this is not enough. It has certainly not repeated the trick achieved by Lagarde’s predecessor Mario Draghi — now the Italian prime minister — who famously turned the tide of the eurozone debt crisis in the summer of 2012 simply by saying the central bank would do “whatever it takes” to save the euro.

For now, the ECB has halted the downward spiral in Italian bonds, stabilising 10-year yields at about 3.6 per cent with the spread at 1.9 percentage points. But investors are hungry for details of its new toolkit.

“All the ECB did [this week] was show it is watching the situation,” says one senior London-based bond trader. “It does not have the leadership that’s willing or able to do what Draghi did. Eventually the market will test the ECB.”

The central bank hopes that by introducing a new bond-buying instrument it will be able to keep a lid on the borrowing costs of weaker countries while still raising rates enough to bring inflation down.

Hawkish rate-setters at the ECB normally dislike bond-buying, but they support the idea of a new tool, believing it will clear the way to increase rates more aggressively. Deutsche Bank analysts raised their forecast for ECB rate rises this year after Wednesday’s meeting, predicting it could lift its deposit rate from minus 0.5 per cent to 1.25 per cent by December.

“Central banks will hike until something breaks, but I don’t think they’re convinced that anything has broken yet,” says James Athey, a senior bond portfolio manager at Abrdn.

Financial asset prices have tumbled, but from historically elevated levels, he says, and policymakers who have in the past been keen on keeping their currencies weak — a boon for exports — are now raising rates in part to support them, to deflect inflationary pressures.

“The [Swiss National Bank] is a case in point,” he says. “All they have done for a decade is print infinite francs to weaken their currency. It’s a complete about face.”

The Swiss surprise leaves Japan as a lone holdout against the tide of rising rates. The Bank of Japan on Friday stuck with negative interest rates and a pledge to pin 10-year government borrowing costs close to zero.

¥135.17

The yen’s value against the dollar on June 13, a 24-year low. The Bank of Japan continues to have negative interest rates

The BoJ can afford to bet that the current bout of inflation is “transitory” — a term ditched long ago by central banks elsewhere in the developed world — because there is little sign that the commodity shock is shaking Japan from its long history of sluggish price rises in the broader economy. Consumer inflation in Japan is hovering at about 2 per cent, broadly in line with targets.

Even so, the pressure from markets has become intense. The Japanese central bank has been forced to ramp up its bond purchases at a time when other central banks are powering down the money printers, to prevent yields being dragged higher by the global sell-off. At the same time, the growing interest rate gulf between Japan and the rest has dragged the yen to a 24-year low against the dollar, spreading unease in Tokyo’s political circles.

The pain from rate rises will be felt globally, Athey predicts. “When the basics that everyone needs to live, like food, energy and shelter, are going up, and then you jack up interest rates, that’s an economic sledgehammer. If they end up actually delivering the tightening that’s priced in then economies are in big trouble.”