I keep hearing from friends who live in Britain that I will be shocked when I get there on Thursday of this week after a nearly four year absence. One friend, who has just returned said that the deterioration in the public infrastructure is now fairly evident. Despite my absence, I have been keeping a regular eye on the data and so these anecdotal reports and reflections come as no surprise. It is obvious that the Tory government has sought a depoliticisation strategy by cutting local government spending capacity as a way of diverting blame for the consequences of their austerity push. The problem now is that after 13 or so years of Tory rule, the cuts are eating into the very essence of civil society in Britain. Like all these neoliberal motivated cuts, the cuts to council grants will prove to be myopic. The dystopia they are creating will come back to haunt the whole nation.

I wrote about this topic in these blog posts:

1. The austerity attack on British local government – Part 1 (April 30, 2019).

2. The austerity attack on British local government – Part 2 (May 2, 2019).

This document published by the House of Commons Library (September 23, 2023) – What happens if a council goes bankrupt? – provides some background on local government bankruptcy rules in the United Kingdom.

It was prompted by ‘Birmingham City Council’s issue of a section 114 notice on 5 September 2023’.

More recently, the Nottingham City Council filed a – Section 114 Report – on November 29, 2023.

The so-called – Section 114 notice – which are reports put out by the Chief Financial Officer of local government that ‘restricts all spending except for that which funds statutory services.’

While technically a local council cannot be declared bankrupt, the Section 114 Report has been interpreted as an ‘effective’ bankruptcy and prompts a new fiscal statement with extensive spending cuts.

The CFO for Nottingham noted when the Report was released that that:

The council is not “bankrupt” or insolvent, and has sufficient financial resources to meet all of its current obligations, to continue to pay staff, suppliers and grant recipients in this year.

But:

… the council’s latest financial position … highlights that a significant gap remains in the authority’s budget, due to issues affecting councils across the country, including an increased demand for children’s and adults’ social care, rising homelessness presentations and the impact of inflation.

The problem for local councils in Britain can be traced back to the massive cuts in grants that they receive from the national government, which since 2010, have been obsessed with austerity and can depoliticise some of the damage by cutting local government income and then blaming the council for the subsequent cuts in services etc.

In Nottingham’s case, the council is Labour run so the blame can be shed onto the political opposition by the Tory national government.

What then follows are accusations from the national government that the local authorities are corrupt or financially incompetent in one way or another, which allows the real cause of the malaise to be hidden within the public debate.

A UK Guardian report late last year (December 6, 2023) – English town halls face unprecedented rise in bankruptcies, council leaders warn – said that around 20 per cent of the local governments in the UK would “fairly or very likely” have to file Section 114 Reports in the next year or so.

I last studied this situation when the Institute for Government released their report – Neighbourhood services under strain: How a decade of cuts and rising demand for social care affected local services – on April 29, 2022.

That Report noted that:

England’s most deprived areas were hit by the largest local authority spending cuts during a decade of austerity … The miles covered by bus routes fell 14% between 2009/10 and 2019/20, with deprived areas more likely to see reductions in routes … A third of England’s libraries closed in the same period, with more closures in the most deprived areas.

It noted the “the scope of the state has shrunk locally, across England” in the decade of Tory rule up to 2019/20.

Councils rationed their spending and scrapped a lot of discretionary projects which add value to their communities.

The problem was two-pronged.

First, the grants were severely cut thus compromising the supply capacity of local governments.

Second, the overall austerity inflicted on the nation as a whole caused a rise in demand for social care services, particularly in the most disadvantaged council areas, which then placed further pressure on the councils.

The Report noted that:

The combined effects of grant cuts and increases in demand for social care squeezed the rest of local authority spending, including neighbourhood services.

Some councils cut neighbourhood services by up to 69 per cent.

Given certain changes in the way the data is collected and classified it is a bit difficult to accurately assess the extent of the cuts to local government in Britain.

But the IFG Report concluded that:

… the UK government reduced grants to local authorities by £18.6bn (in 2019/20 prices) between 2009/10 and 2019/20, a 63% reduction in real terms.

That is a massive slug and the situation has worsened since as the cost-of-living pressures have increased following the early years of the pandemic.

Councils can respond by increasing the annual council taxes but as the House of Commons briefing (cited above) indicates – “Since 2012, the Government has set national limits on the amount council tax can be raised by annually” – which in the present situation means that there cannot be a ‘real’ increase in council tax revenue, given the national inflation rate, although there have been some exemptions where the financial situation is consider dire.

The most recent detailed time series data for annual local government expenditure was released by the Office of National Statistics on February 21, 2023 – https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/governmentpublicsectorandtaxes/publicspending/datasets/esatable11annualexpenditurelocalgovernment.

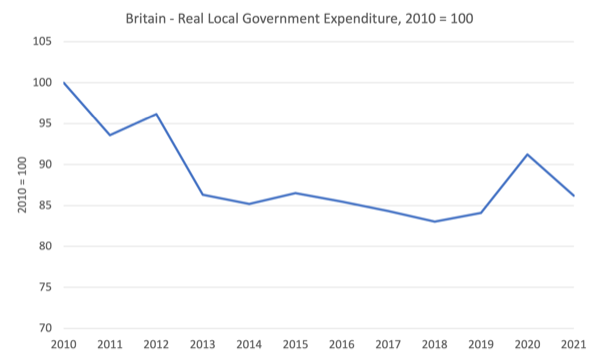

The following graph shows that between 2010 and 2021 (latest observations), real (CPI adjusted) total local government expenditure fell by 13.8 per cent.

When we get data for 2022 and 2023, the real cuts will be much worse than this and the demands on emergency, social care expenditures will have increased.

In effect, the Tories, among other sins, have ripped apart the very basis of civil society in Britain and the consequences will be long-lived.

The IFG reported – Local government funding in England (updated July 21, 2023) that total local government income (from “government grants, council tax and business rates”) was 10.2 per cent below 2009/10 levels by 2021/22.

They noted that:

The fall in spending power is largely because of reductions in central government grants. These grants were cut by 40% in real terms between 2009/10 and 2019/20 …

There is a major social-spatial dimension to this dilemma as well.

The poorer local government areas have lesss capacity to generate cash from council taxes and business rates than the more affluent places.

The demand for social care services is also higher in the most disadvantaged areas.

But the malaise is general.

I read a recent BBC report (January 9, 2024) – Hampshire waste tips and museums at risk as council cuts £132m – that some council authorities are going to turn their street lights off at midnight as well as other cuts to essential services.

There are two points I would make about this situation.

First, many of the cuts (museums, libraries, etc) are dismissed by people as being the domains of the work who should pay for these services themselves.

I read an Op Ed this morning where calls for degrowth is a woke demand that denies the reality of people in the so-called global south.

I will write about that in the future but I reject that criticism.

We do have lift people out of material deprivation but that can be done without relying on past fossil fuel technologies.

It is not an either-or or zero sum game.

So, the Tories to some extent have been able to get away with these types of cuts because the buses still run, etc.

But what has been happening as a result of these stringent cuts by the national government is that local authorities have been diverting some longer-term spending into short-run emergency needs.

For example, diverting housing spending into crisis accommodation to help keep people off the streets.

So the story is a bit like this:

1. The central government squeezes total funds available to local authorities.

2. It increases or maintains their spending responsibilities.

3. Population grows and ages.

4. Overall austerity increases the number of people reliant on council service delivery.

5. Local authorities divert their shrinking funds into crisis areas.

6. They cannot cope.

7. They start drawing on their finite reserves.

8. Eventually, with public infrastructure in a degraded state due to lack of maintenance, people still in need, the local authorities are issued with so-called Section 114 notices – signifying they are “at risk of failing to balance its books in this financial year”.

9. At that point, the local authority is in breach of the law and the system of government becomes unsustainable.

But, it goes deeper than this.

I have argued before that these neoliberal-instigated changes represent a myopic strategy even if for the local governments they become essential given the crisis.

For example, see these blog posts, among others:

1. The mindless and myopic nature of neoliberalism (January 9, 2019).

2. More privatisation myopia (March 22, 2021).

3. We are undermining our futures by deliberately wasting our youth (March 2, 2021).

4. Mental illness and homelessness – fiscal myopia strikes again (January 5, 2016).

5. British floods demonstrate the myopia of fiscal austerity (January 4, 2016).

6. Public R&D austerity spending cuts undermine our grandchildren’s future (October 21, 2015).

7. The myopia of fiscal austerity (June 10, 2015).

Eventually, the strategy backfires and the outlays necessary to repair the damage outweighs the so-called ‘savings’ in the short-run.

The cited blog posts provide many examples of this myopia.

So, either civil society collapses or the national government has to eventually pay up to fix the damage done.

Then the payout is massive.

All the talk about the ability of privatisation and PPPs to risk shift (from public to private) is false.

The risk can never shift for an essential service – the state always has to pick up the tab when the private provider fails.

Second, the problem the Labour Party faces is now massive and their talk of fiscal prudence and rule-driven decision-making suggests to me that the crisis facing local governments will not be adequately addressed by them should they take power at the next general election.

I read a quote from Starmer while he was visiting Leicester recently – one of many cities in fear of the need to publish a Section 114 Report.

The Leicester Mercury article (January 9, 2024) – Keir Starmer says no quick cash for hard up Leicester if Labour wins general election – said that:

In Leicestershire alone, the city council has said filing an S114 is all but inevitable in the next 18 months, and the county council’s leader has said this year’s budget was the most challenging he had known.

And what did Starmer offer?

Nothing:

Local government funding has been a real problem. We’ve seen in a number of places, whether it’s Conservative-led or Labour-led, councils … [are] … struggling with finances. This is a result of the funding structure from the government, which is much too short term …

We’ll have to live within the constraints of an economy that’s been badly damaged in the last 14 years. So I’m not going to make promises I can’t keep.

So don’t hold your breath hoping that when Labour assume office the situation will change.

Fiscal rules that work against public purpose are part of the myopia I noted above.

Conclusion

Local governments are also going to be essential partners in the climate change response.

At present, the funding cuts are working against that need.

So not only is civil society being eroded, but the longer term responses are being undermined.

Human civilisation as we have known it over the last century – with all the ‘progress’ that has been made – is now becoming terminal.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2024 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.