When I met with John McDonnell on October 11, 2018 at his Embankment office block in London he was then the Shadow Chancellor. The theme of the meeting was dominated by the concerns (near hysteria) about the power of the City of London (the financial markets), expressed by his advisor, a younger Labour Party apparatchik whose ideas are representative of the bulk of the progressive side of politics in Britain. The topic of the meeting centred on the fiscal rule that the British Labour Party chose to apparently establish credibility with the financial markets (‘The City’). I had long pointed out that the fiscal rule they had designed with the help of some New Keynesian macroeconomists was not just a neoliberal contrivance but was also impossible to meet and in that sense was just setting themselves up to failure should they have won office at the next election. Essentially, I was just met with denial. They just rehearsed the familiar line that the British government has to appease the financial interests in The City or face currency destruction. That fear is regularly rehearsed and has driven Labour policy for years. It wasn’t always that way though. As part of preliminary research for a book I plan to write next year I am digging into the history of this issue. What we learn is that the British government has all the legislative capacity it needs to render The City powerless in terms of driving policy. That raises the question as to why they don’t use it. All part of some work I am embarking on. The reason: I am sick to death of weak-kneed politicians who masquerade as progressive but who bow and scrape to the financial interests in the hope they will get a nice revolving door job when they exit politics. A good motivation I think.

The problem with Labour’s fiscal rule – which persists in the current Labour policy setup – is that in times when the private sector is buoyant, the government which adopted such a rule would probably find they could work within it and still provide some spending support for necessary projects.

But that would be a rare scenario.

In a period of slower private spending growth or an actual move towards recession, a fiscal rule such as the Labour Party has adopted would quickly fail due to the impacts of the cyclical shifts in revenue and spending (the ‘automatic stabilisers’) and at that point the government would have to do abandon the rule.

Such a shift in stance would come with significant political costs and open the government to accusations that it was financially incompetent, given that, by they effectively defined financial competence as meeting such a fiscal rule.

Adherence to such a unnecessary rule in the first place, given that the final fiscal balance each period is not able to be controlled by the government anyway, is always unwise.

I discussed the meeting in this blog post – A summary of my meeting with John McDonnell in London.

Labour did not win the next election and the changes in the leadership of the Party have seen not only the purges of the progressive elements but also an even greater obsessiveness about The City and what it might do if Labour dared run a progressive policy agenda.

I noted in the discussion with John and his team that the size of the financial sector in Britain is not dissimilar to its size in Australia – which was an attempt to allay their claims that the UK was a special case because its financial sector was so large relative to the size of the financial sector in other nations.

At any rate, British Labour hasn’t changed.

Rather, it has become more obsessively constrained by the view that it must please The City or else fail.

Recent comments and actions by Leader Starmer and Shadow Chancellor Reeves confirms that.

They should, instead, think back to the immediate Post World War 2 period when Clement Attlee successfully legislated a range of progressive policies that ran counter to the wishes of The City.

And in those days, financial capital had more capacity to do damage than it has now because the exchange rates were fixed, which meant they became prey for speculators.

Anyway, as preliminary research for a book project I intend to pursue next year – I have two books in train at present – one which will be published on July 15 (See below) – and another, hopefully later in 2024 – I have been accumulating information about The City and how government became so scared of it.

The story that is emerging tells me it is an elaborate con and the British government has all the legislative power to bring the financial markets to heel.

The question I haven’t yet answered but am approaching an answer is why don’t the politicians do it?

I read an interesting article the other day – The City of London: Geopolitical Issues Surrounding the World’s Leading Financial Center – which was published in the French journal Hérodote (Revue de géographie et de géopolitique), Vol. 151, No. 4, 102-119 (the link is to a translated version).

The author asks the question: “Who indeed does administer the global finance system and where is this administration located?”

He focuses on the ‘City of London’ as the “greatest of all” and notes that it embedded in a “structured organiation” in the form of the “City of London Corporation (CLC)”, which:

At a national level, the CLC intervenes directly in the economic policy of the British government, while at the level of British overseas territories and crown dependencies, it makes use of a network of tax shelters.

The ‘City of London’ is “nicknamed the ‘Square Mile’ … and does not actually refer to a territory, but to all the financial service activities associated with Greater London.”

The mission of the CLC is “to promote the City’s financial services throughout the world … In short, it has to run the world’s leading financial center and do so in a way that ensures it remains at the top.”

We read that “The CLC is unique to the City of London and its independence is marked by exceptional privilege” that goes back before William the Conquerer became the King.

Further:

Another distinctive feature of the CLC is that its administration has significant funds at its disposal, which it invests in line with the policy chosen by the Common Councilmen and Aldermen. This gives it a lobbying power that is beyond that of any other administration. Its financial power comes from three funds (City Bridge Trust, City Fund, and City’s Cash … whose assets are unknown, but estimated to be three billion euros (Shaxson 2012) and most certainly include real estate assets throughout the entire world.

So a big bully with cash.

But even then the CLC lost a major court case in 2002 when activists successfully delayed a property development that the City was pushing which would destroy a local working-class neighbourhoods.

Here is some background to that fight:

1. Save Spitalfields from market forces (July 15, 2001).

2. Tales of the City: Spitalfields under threat (October 9, 2002).

We also know that ‘The City’ has:

… branches that feed it are mainly to be found in the British overseas territories and Crown dependencies, which regularly vaunt their financial opacity and concealment like an advertising campaign … These nine territories represent 2,800 billion dollars in deposits. In comparison, Switzerland has 1,200 billion dollars and Luxemburg, 900 billion.

And guess what?

The United Kingdom provides them with defense and security, and manages their foreign affairs in concert with their local governments. It is generally agreed that these are the black holes of world finance. In the second quarter of 2009, for example, City banks received 332.5 billion dollars from its three dependencies … these territories are the port of entry for significant capital flows into the London financial center, which is therefore being fed capital lacking in transparency.

Which means:

The British authorities and, to an even greater extent, the CLC hide behind the ceremonial sovereignty of these nine territories to absolve themselves from having any control over these funds and from any responsibility as to their origins. The City banks use them like capital pumps feeding its markets. However, these territories are very politically and economically dependent upon the United Kingdom. It is difficult to believe that the British Chancellor of the Exchequer is incapable of persuading or pressuring these territories to clean up their financial markets and institute stricter controls and regulations. Once again, the role of the CLC is of prime importance. It certainly has no interest in such measures and is quick to remind the British government of the fact.

So, when one is confronted with the claims that British Labour must appease ‘The City’ or face currency destruction, the real question is why doesn’t the British government exercise its legislative capacity to control the sources of any capital flows that might cause currency disruption?

That is the nub.

While ‘The City’ masquerades as all powerful, it could be brought to heel relatively easily through appropriate legislative interventions.

Of course, ‘The City’ lobbies relentlessly.

We learn that:

In order to monitor the work of Parliament so that it would never interfere with the power of the CLC, a chair was installed in 1571 beside the Speaker’s chair in the House of Commons, where an officer of the CLC, called the Remembrancer, still sits today. The City of London is thus the only British territory to have installed an official lobbyist within the House of Commons itself, who makes sure that the rights and privileges of the Square Mile are preserved.

So there is a “non-democratically elected officer who participates in the sessions of the British Parliament” and is there on privilege which would be revoked.

I have been tracking down discussions about this seemingly ridiculous medieval practice and came across the 1937 book by the Leader of the Labour Party – Clement Attlee – who later became Prime Minister (in 1945).

In this book – The Labour Party in Perspective – Attlee provides an interesting account of the powers of government and how they can implement them.

He writes that (p.178-179):

Some of these powers are already in the hands of Government, and only the will and vision are lacking … despite these encroachments by the Govern- ment on the sphere of private enterprise, the main controls of the economic system remain in the hands of those whose actuating motive is private profit. It is to the securing of these controls for the service of the community that the Labour Government will turn its hand.

He then addressed the question of first “importance …financial power” and wrote (p.179):

Over and over again we have seen that there is in this country another power than that which has its seat at Westminster. The City of London, a convenient term for a collection of financial interests, is able to assert itself against the Government of this country. Those who control money can pursue a policy at home and abroad contrary to that which has been decided by the people. The first step ni the transfer of this power si the conversion of the Bank of England into a State institution.

He noted that The City had been running a scare campaign opposed to the nationalisation of the bank – for example, “to seize the savings of the well-to-do”

Significantly, even though Attlee succeeded in nationalising the Bank of England, in 1998 Tony Blair “gave the central bank total independence”.

Blair also:

… changed the voting system in the chambers of the CLC by authorizing that businesses could vote alongside the City of London residents. This, in fact, handed power over to the business vote due to the relative population sizes: 7,000 residents versus 24,000 business representatives.

So the Labour Party, which continually expresses fear of The City, used their legislative power while in office to give The City even more power.

The Labour Party also still play along with the Mansion House charade – which is when the Chancellor of the British Government is “invited each year to appear before the Lord Mayor at the Guildhall (in the City of London) and at the Mansion House (the Lord Mayor’s residence) to justify his or her actions and present their plans for future financial policy.”

The City thus makes sure that government policy will always promote The City.

In another 2014 article I read by Sukhdev Johal, Michael Moran and Karel Williams – Power, Politics and the City of London after the Great Financial Crisis – (published in Government and Opposition, Vol. 49, No. 3, 400-425) – we consider “two dominant questions” that “have shaped power relations: what is to be the relationship between the City of London and the (formally) democratic system of UK government in which it is embedded; and what is to be the role of competition in the workings of financial markets?”

A clue is that in the recent decades “we can see the City organizing itself as a conventional professional lobby designed to ensure victory in struggles over overt decisions.”

And “Finance may still be dominant, but its power is increasingly precarious because it now fights on terrain not of its choosing, where outcomes are uncertain.”

Conclusion

What we will learn when I next write about these matters is the way in which The City got to this precarious situation.

The next installment in this little series of blog posts will also cover the period 1945 to the OPEC oil shock when Labour governments in Britain were able to introduce a swathe of reforms that advanced the well-being of the people and which were hated by The City.

Income was redistributed.

A massive and sophisticated public housing agenda was pursued which rejected the suggestions from The City that the government should only offer rent subsidies in the private markets – which would have channelled huge cash flows to the rich landlords who like any subsidy would have just scaled up the subsidy attractor (that is the private rents).

Instead, the government introduced controls on rents and provided increased security for tenants while building a stack of dwellings throughout Britain.

That is enough for today!

Advance orders for my new book are now available

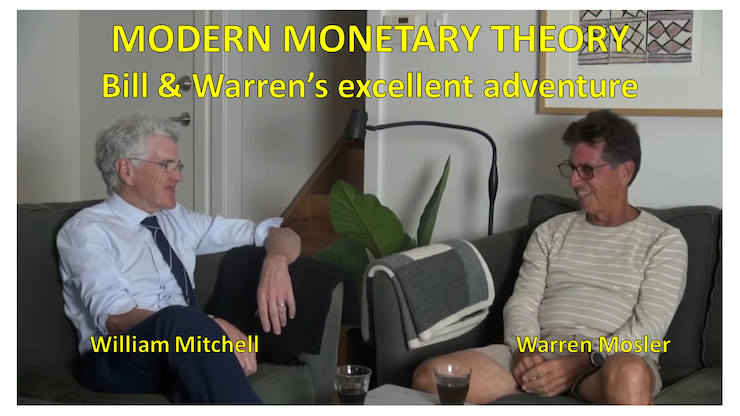

I am in the final stages of completing my new book, which is co-authored by Warren Mosler.

The book will be titled: Modern Monetary Theory: Bill and Warren’s Excellent Adventure.

The description of the contents is:

In this book, William Mitchell and Warren Mosler, original proponents of what’s come to be known as Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), discuss their perspectives about how MMT has evolved over the last 30 years,

In a delightful, entertaining, and informative way, Bill and Warren reminisce about how, from vastly different backgrounds, they came together to develop MMT. They consider the history and personalities of the MMT community, including anecdotal discussions of various academics who took up MMT and who have gone off in their own directions that depart from MMT’s core logic.

A very much needed book that provides the reader with a fundamental understanding of the original logic behind ‘The MMT Money Story’ including the role of coercive taxation, the source of unemployment, the source of the price level, and the imperative of the Job Guarantee as the essence of a progressive society – the essence of Bill and Warren’s excellent adventure.

The introduction is written by British academic Phil Armstrong.

You can find more information about the book from the publishers page – HERE.

It will be published on July 15, 2024 but you can pre-order a copy to make sure you are part of the first print run by E-mailing: info@lolabooks.eu

The special pre-order price will be a cheap €14.00 (VAT included).

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2024 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.