At the Money: Avoiding the Behavior Gap with Carl Richards, May 22, 2024

Why do investors underperform their own investments? Why does this happen, and what can we do to avoid these poor outcomes? In today’s At the Money, we discuss how to better manage the behavioral errors that hurt portfolios.

Full transcript below.

~~~

About this week’s guest: Carl Richards is a Certified Financial Planner and creator of The New York Times Sketch Guy column. Through his simple sketches, Carl makes complex financial concepts easy to understand. He is the author of The Behavior Gap: Simple Ways to Stop Doing Dumb Things with Money.

For more info, see:

~~~

Find all of the previous At the Money episodes here, and in the MiB feed on Apple Podcasts, YouTube, Spotify, and Bloomberg.

TRANSCRIPT: Carl Richards

[Musical Intro: Ain’t misbehaving, saving all my love for you]

Barry Ritholtz: How many times has this happened to you? Some interesting new fund manager or ETF is putting up great numbers, sometimes for years, and you take the plunge and finally buy it. It’s a hot fund with tremendous performance, but after a few years, you review your portfolio and wonder, hey, how come my returns aren’t nearly as good as expected?

You may be experiencing what has become known as the behavior gap. It’s the reason your actual performance is much worse than the fund you purchase.

I’m Barry Ritholtz, and on today’s edition of At The Money, we’re going to discuss how to avoid suffering from the behavior gap.

To help us unpack all of this and what it means for your portfolio, let’s bring in Carl Richards. He’s the author of The Behavior Gap, Simple Ways To Stop Doing Dumb Things With Money. The book focuses on the underlying behavioral issues that lead people to make wrong decisions. Poor financial decisions.

So Carl, let’s just start with a basic definition. What is the behavior gap?

Carl Richards: Thanks Barry. Super fun to chat with you about this. This is going back now 20 years, right? Like I just stumbled upon this early on in my work with investors. That we would get all excited. I would get all excited! Exactly as you said like we would do some performance review, we would find some fun. We thought was great. Of course, past performance is no indication of future results.

But what’s the first thing you look at? [past performance] When you decide to make yeah past performance get all excited about it And then you have this inevitable letdown and so I think the easiest way to describe this is imagine you open the newspaper; and, uh, there’s an, there’s a advertisement. Remember the old fashioned newspaper, right? There’s an advertisement for a mutual fund that says 10-year average annual return of 10%.

Well, that’s the investment return. And I think we all forget that investments are different than investors. And so the behavior gap is the difference between the investment return and the return you, uh, earn as an investor in your account. And that’s, My experience and the data show that often individual investors underperform the average investment.

So this well intentioned behavior of finding the best investment is generating a suboptimal result for us as investors.

Barry Ritholtz: So what’s the underlying basis for that gap? I’m assuming, especially if we’re talking about a hot fund, the fund has had a great run up people by if not the top, well certainly after it’s had a big move and then a little bit of mean reversion comes back into it.

The fund does poorly for a couple of years and then kind of goes back to where it was. Is it just as simple as buying high and, and being stuck with it low? Is, is it that simple?

Carl Richards: Yeah, I, it’s interesting. Let me just tell you a quick story. And this is about all, all great investment stories are about your father-in-law, right? So I remember my father-in-law in ’97, ’98, ’99. He had an investment advisor. His advisor was named Carter. I remember all this. And he owned, and I can name specific funds because these things are not the problem, the fund didn’t make the mistake, right? So, Alliance Premier Growth, if you remember, 97, 98, 99, just, you know, he owned Alliance Premier Growth, and he owed Davis Value Fund, so go-go growth fund, and something that was classically value.

And at the end of ’97, he looks at his returns and he’s like, why do we own this? Then this Davis, this value fund, why do we own this thing? Carter talks him into rebalancing, which means he took some from Alliance premier growth, moved it to Davis opposite of what he felt like doing. Right.

98 comes around. Same thing. The Alliance premier growth knocks it out of the park. Davis only does like 12 percent or something. Right. Father in law complains. Carter says, hey, please, come on. Like, this is just, this is just what we do. We’re actually going to do the opposite of what you feel. We’re going to sell some Alliance Premier Growth, we’re going to rebalance into Davis. ‘99, right? And I can’t recall the exact numbers, but if Alliance did something like 54%. And Davis only did 17%.

And my father in law was like, that’s it. That’s it. And I remember New Year, like over Christmas, over the Christmas holiday of 99. Right. And you know what happens next?

He tells me, he’s like, yeah, I finally had enough. I fired those Davis, that Davis New York venture fund and moved all the money to Alliance premier growth just in time. You know, we have another, he felt like a hero for January, February, and then March of 2000, just in time to get his head taken off. And we repeat that over and over.

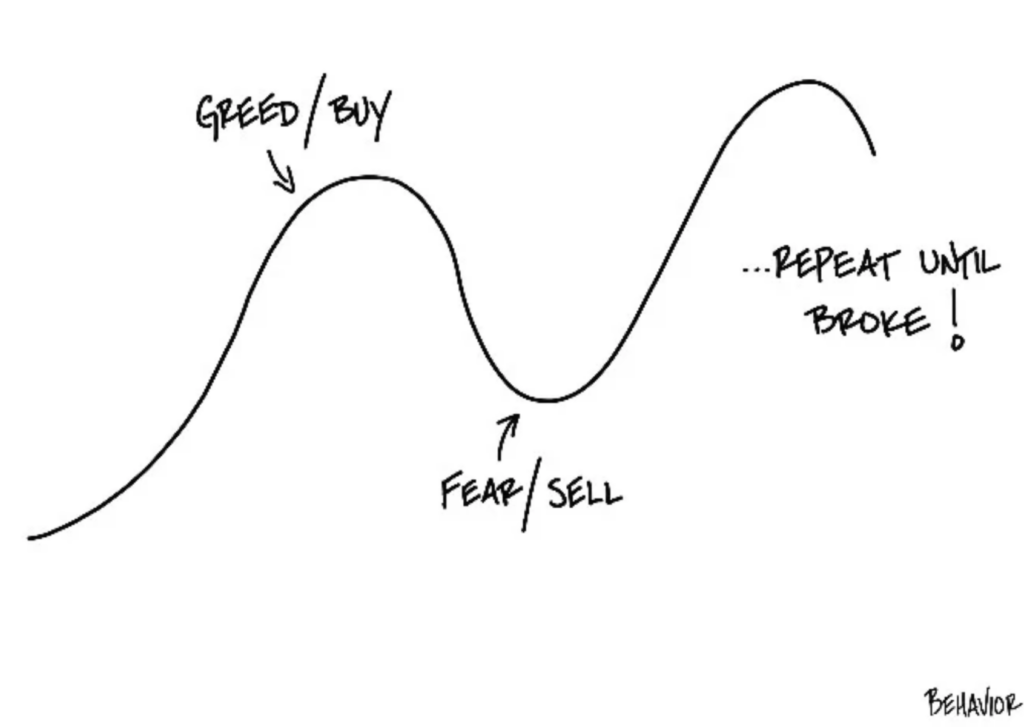

And it’s, it’s kind of wired into us. So it’s, it’s challenging. You want more of what gives you security or pleasure. And you want to run away from things that cause you pain as fast as possible. And somehow we’ve translated that into buy high and sell low and repeat until broke.

Barry Ritholtz: And I happen to have, the number one of that series of lithographs you did. Repeat until broke. Hanging in my office.

And, and let’s put a little, a little meat on the bones, if you, if you were heavily invested in any fund that was heavily exposed to the NASDAQ, from the peak in March 2000 to just two years later by October of 02, the NASDAQ was down about 81 percent peak to trough.

Yeah. That’s a hell of a haircut losing four fifths of, of the value.

Carl Richards: Especially just I mean I remember those conversations like there was I mean this is kind of fun to poke fun at your father-in-law, right, but it wasn’t very fun when there was like some pretty major drastic changes in the way the family was operating Because of that experience like it was it was a real deal for lots of people, right?

And Barry just to point out like that was not Investment mistake. That was an investor mistake, right? If you had just stuck to the plan, which is rebalance each year, you would have been fine. It would have been painful, but not nearly as painful as it turned out to be.

Barry Ritholtz: And I would bet the Davis Value Fund did pretty well in the early 2000s, certainly relative to the growth fund.

Carl Richards: For sure. You would have been protecting that. You would have been systematically Buying relatively low and selling relatively high along the way, systematically, because it’s just what you do, and that’s called rebalancing.

Barry Ritholtz: So, the behavior gap creates this space between how the investment performs and how the investor performs how big can that gap get how large?

Does the behavior gap between actual fund performance and investor returns become?

Carl Richards: Yeah, this is really problematic because there are a couple of different studies and none of them are great. My experience with it is more anecdotal like experiences. I have like the story I just told I could tell 20 of those stories You Right.

Given, I mean, did anybody listening become a real estate investor in ‘07, right? Like over, uh, you know, we, we don’t have to even go into the, Crypto NFT situation, right? But just over and over we do it, but Morningstar numbers, I think are my favorite and that always puts it around a 1%, a percent and a half over long periods of time. Which when we’re all scraping for 25 basis points, you know, running around trying to eke out the last bit of return, then this behavior gap that costs us a point to a point and a quarter is something worth paying attention to.

Barry Ritholtz: Yeah, especially as, as how that’s compounded over time, it can really add up to something substantial. So let’s talk about where the behavior gap comes from. It sounds like our emotions are involved. It sounds like fear and greed is what Drives the behavior gap tell tell us what you found.

Carl Richards: Yeah, it’s funny when I originally found this, I felt like this was a discovery, (you know cute of me) because lots of other people have been writing about It for years. I was trying to put a name on this gap and I called it originally the “Emotional gap” I’m really glad I changed the name to the behavior gap for the book but to me there was just I couldn’t explain it other than or investor behavior and I think You When we understand how we’re wired and I can’t remember who was it Buffett that said of course We could just we can always attribute it to Buffett if it was smart, but it was “If you want to design a poor investor, design a human.” right?

We’re hardwired and it’s kept us alive as a species: To get more of the stuff that’s giving us security or pleasure and to run as fast as we can Like I don’t really care. I don’t care what you tell me if my hand’s on a burning stove, I’m gonna take it off. Throw all the facts and figures you want at me.

Try to be rational with me all day long. I’m, I’m taking my hand off. And somehow, especially given the sort of circus that exists around investing, you know, where you got people yelling and screaming, buy, sell, buy, sell all day long. We translate market down, market down. Oh no, if I don’t do something and we project the recent past and definitely in the future, and I’ve seen people actually do the calculations.

If the last two weeks continue. In 52 weeks, I’m going to have no money left. [the market’s going to zero!] Yeah. We have this recency bias problem. We have being hardwired for security and pleasure. We have safety herd behavior. When all your neighbors are yelling, right. It’s really hard not to you know,

It was a Buffett quote, right? “I want to be greedy when everybody else is fearful and fearful when everybody else is greedy” and that’s cute to say. But when you’ve actually been punched in the face, you behave a little differently, right?

Barry Ritholtz: So the other thing that I noticed that you’ve written about regarding the behavior gap is how much we focus on issues that are completely out of our control.

What’s happening with markets going up and down? Who is Russia invading? What’s happening in the Middle East? When’s the Fed going to cut or raise rates? All of these things are completely outside of not only our control, but our ability to forecast. What should investors be focusing on instead?

Carl Richards: Yeah, I think portfolio construction, when done correctly, it takes into account the weighty evidence of history, and the weighty evidence of history includes all of those events that we couldn’t have forecasted before.

So we shouldn’t be surprised that things that we didn’t think about will show up next year and next week. And those things that we didn’t think about will have the greatest impact on our portfolio. So it’s literally like the unknown unknowns that will have the greatest impact. We’ll design the portfolio with that in mind.

Well, how do you do that? We’ll use the weighty evidence of history because it’s been going on for a long time. So I think the way to focus on what, like the thing you can control the most is portfolio construction, asset allocation, and costs. Like if we just get clear about that. The portfolio is designed.

Here’s a question to ask you. I’ve been asking this question as like a a game for the last five years. Why is your portfolio built the way it is? And the most common answer is, like I heard about it on the news, the really smart people whisper, “I read about it in The Economist.” Right? But the correct answer is, this portfolio is designed intentionally to give me the greatest chance of meeting my own goals. Well, those are the things you can focus on.

Barry Ritholtz: Quite intriguing. So to wrap up, when investors chase hot funds or ETFs or sectors or whatever is the flavor of the moment, there’s a tendency to buy high, and if subsequently they get out of these buys, positions or sell into a panic or market correction, they’re all but guaranteed to generate a performance worse than the fund itself.

To avoid succumbing to the behavior gap, you must learn to manage your own behavior. I’m Barry Ritholtz, and this has been Bloomberg’s At The Money.

[Musical Outro: Ain’t misbehaving, saving all my love for you]

~~~