The Australian – Productivity Commission – was created in 1998 as a result of an amalgamation between the Industry Commision (established 1990), the Bureau of Industry Econmics (established 1978) and the Economic Planning Advisory Commission (established 1983). As you will read below, its antecedents go back to 1921. The Commission is one of many government-funded institutions that have undergone structural shifts over time as their initial role becomes redundant, a reduncancy that reflects the changing dominant ideology of the time. It is now the government’s principal ‘free market’ think tank that spews out predictable nonsense regularly – always ending with recommendations for more deregulation and less government intervention. Its latest offering was released on Monday (May 20, 2024) – A snapshot of inequality in Australia – which, in its own words, “provides an update on the state of economic inequality in Australia, reviewing the period of the COVID-19 induced recession and recovery” with a focus on women, older people, and First Nation’s peoples. It contains some interesting analysis but falls short because its fiscal framework, upon which it makes assessments about the data that is made available, is mainstream and assumes the Australian government has financial constraints. Once they adopt that fiction, then the scope for policy is limited and we end up not solving the problems discussed.

Last week (May 14, 2024), the Federal Treasurer delivered the annual – Fiscal Statement 2024-25 (aka Federal ‘Budget’)- which defines the discretionary fiscal stance over the next 12 months.

I usually provide a detailed analysis of this statement but it is such a demoralising task that this year I decided to steer clear.

I am in the last week of finalising the manuscript for my next book (with Warren Mosler) that will be published on July 15, 2024 (for details and pre-order details see below) and so I decided that my time was better spent doing that rather than getting depressed about politicians who celebrate recording a fiscal surplus, which has been enabled because the government is squeezing the prosperity (and wealth) from ordinary citizens and pursuing a deliberate strategy to impoverish some of the most disadvantaged Australians.

There is nothing to celebrate about that.

The RBA has been trying to destroy jobs for the last two or so years through their relentless and unnecessary interest rate hikes.

The NAIRU, according to the mainstream logic defines the state where inflation is stable.

I reject the concept and its derivation, but let’s run with it to test its internal consistency.

The RBA has claimed justification for hiking interest rates even though inflation was declining rapidly because they claimed that the NAIRU, which is unobservable but estimated through econometric methods, is around 4.25 per cent.

The official unemployment rate has been well below the RBA’s estimate for years now and so according to the NAIRU logic should see inflation continuing to accelerate.

But inflation has been declining in Australia since September 2022, at a time when the unemployment rate was very stable at around 3.7 to 3.9 per cent.

Which means that logically, the NAIRU could not be above the current unemployment rate and must be below it.

On that basis, with inflation in decline, even if we accept there is a definable NAIRU that can be measured somehow, the RBA’s narrative is plainly wrong.

Which means that the RBA’s insistence on putting 140,000 extra workers onto the unemployment scrap heap has no foundation even in the theoretical structure they believe in.

The Federal government also is trapped in the same false logic.

In the – Budget Paper No. 1 – released last week, we learn that the government is forecasting as a result of its discretionary fiscal policy settings that the unemployment rate will rise from its actual level of 3.6 per cent in 2022-23 (average) to 4 per cent by the end of this financial year (June 2024), then rise to 4.5 per cent over the course of the next 12 months and remain at that elevated level until the end of 2025-26.

However, as usual, the Treasury numbers do not add up in terms of being internally consistent.

If we put the participation rate, employment and underlying population growth estimates out to 2025-26 together in the labour force framwork, and then calculate the growth in the labour force and the implied rise in unemployment, the simulation shows the government is vastly underestimating the shift in unemployment over its forward estimates.

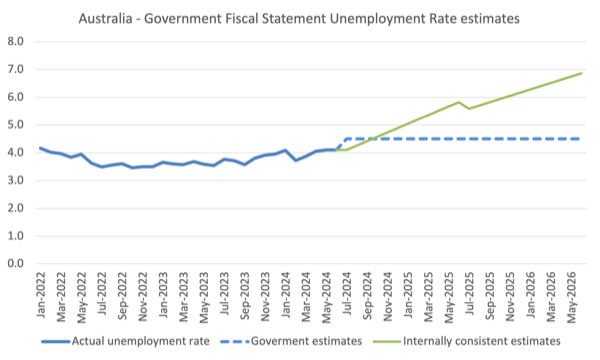

The following graph captures this.

The solid (blue) line up to April 2024 is the actual official unemployment rate.

The dotted line is the Government’s forward estimates as they appear in Budget Paper No. 1.

The solid (green) line above that is the projection one gets of the unemployment rate, if we assume underlying population growth is constant, and take on board the Government’s forward estimates of employment growth and the participation rate.

By that projection the unemployment rate at the end of the fiscal year 2025-26 will be 6.86 per cent, rather than the Government’s projection of 4.5 per cent.

In terms of people, the government is projecting that unemployment will rise to 706 thousand compared to April 2024 figure of 604.2 thousand, a different of just over 100 thousand.

My projections suggest that total unemployment will rise to 1,077 thousand.

Quite a discrepancy.

Another way of checking this arithmetic is to use the rule of thumb from Arthur Okun, which says that for the unemployment rate to remain constant, GDP growth has to be equal to the sum of the growth in the labour force and labour productivity.

I did some calculations along those lines and they confirm the fact that based on the Government’s population and employment growth estimates, the unemployment rate will rise more significantly than the Government’s unemployment forward estimates.

Employment growth will not keep pace with the underlying population growth.

One thing we know categorically is that when there is mass unemployment, it means that the fiscal deficit is too low and is failing to leave the spending gap that results from non-government sector spending and saving decisions.

Running a fiscal surplus when the labour market is in the current and projected state is callous economic policy.

There is a lot more I could say about the Government’s current fiscal strategy as announced last week.

But the thing I really want to focus on is the treatment of the workers that the Government is deliberately (that is, by choice) consigning to the jobless queue.

It is not enough for this Government just to create this unemployment through its fiscal surplus strategy.

They also are deliberately keeping that increasing cohort in abject poverty through their refusal to increase the income support pay for the unemployed above the poverty line.

The last time I analysed this sitution was in this blog post – The so-called Inclusion Committee that recommends keeping the unemployed impoverished (April 19, 2023).

There are many references to the analyses that I have done on this topic over many years.

The situation for the unemployed keeps deteriorating.

Which brings me back to the Productivity Commision report cited in the Introduction.

As background, the Productivity Commission (PC) started life well before the creation in its current form in 1998 and we can trace its antecedents back to the creation of the Commonwealth Tariff Board in 1921, which was replaced by the Industries Assistance Commission in 1974, and then absorbed into the Industry Commission in 1990.

The evolving titles of these government bodies tells you that the Productivity Commission has undergone structural shifts over time that reflect the changing dominant ideology.

This is similar to the evolution of the IMF and the World Bank.

The former was a Keynesian outfit until the 1970s whence it morphed into front-line, neoliberal attack dog and enforcer, the role it plays today.

The evolving nature of these organisations comes about because, in part, the original roles they were assigned become redundant and so they have to find a new function that befits the ideological outlook.

In the case of the Productivity Commission, it began life as a body to administer the system of tariff protection that was put in place by the Australian government in the early 1920s under the banner of the ‘infant industry’ protection.

Australia was industrialising and it was thought the emerging manufacturing sector would require help to develop economies of scale and efficient production.

In the 1970s, the protection was largely withdrawn as neoliberalism started to infest the minds of the polity, and the Board morphed into the Industries Assistance Commission.

When the neoliberalism became more entrenched, the Labor government decided it was no longer in the business of industry policy (‘assistance’) and was more focused on deregulation etc – the body dropped the Assistance from the title.

Then once the ‘free market’ narratives had totally subsumed any idea that the government might actually intervene to assist workers etc, the Productivity Commission was born.

The PC Report shows that:

1. “The years during and following the COVID-19 pandemic have seen significant swings in income and wealth (the value of assets such as houses).”

2. “The pandemic lockdowns drove significant temporary changes in employment and a vast increase in direct government assistance through programs such as JobKeeper and the Coronavirus Supplement.”

3. “Inequality in Australia was relatively stable in the decade leading up to the COVID-19 pandemic, but fluctuated significantly during the COVID-19 induced recession (in mid 2020) and recovery.”

4. “The initial period of the pandemic saw an unprecedented fall in income inequality. The incomes of lower-income households grew rapidly in relative terms as a result of the significant increase in support payments from the Australian Government.”

5. “Income inequality subsequently increased as the economy recovered. Government support was phased out and the incomes of low income households fell.”

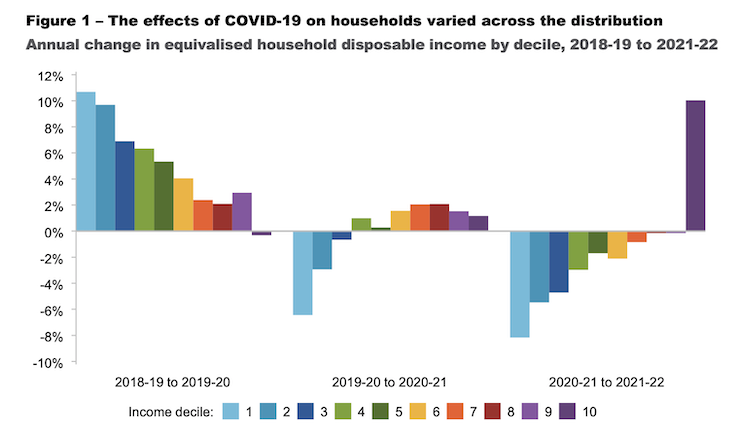

The PC’s Figure 1 summarises the effectiveness of the government assistance during the early years of the pandemic on the different income deciles.

It is a stark graph.

In terms of wealth inequality, the PC Report concludes:

Wealth inequality (the relative value of people’s assets like their homes or superannuation) appeared to decline during the pandemic period. The income received over the period meant that households with lower wealth were able to increase their savings and reduce their debts, contributing to a reduction in wealth inequality. House price changes during the pandemic further reduced wealth inequality, as price growth was relatively higher in areas with lower prices, such as smaller capital cities and regional areas.

There is a lot more in the Report which I will discuss at a later date.

But the relevant part of the PC Report for today’s theme is this conclusion:

The initial period of the pandemic saw an unprecedented fall in income inequality. The incomes of lower-income households grew rapidly in relative terms as a result of the significant increase in support payments from the Australian Government (figure 1). This included the Coronavirus Supplement, which was paid to income support recipients, such as those receiving JobSeeker and Youth Allowance. JobKeeper payments to lower-income part-time workers also contributed to lower inequality early in the pandemic

period. While these programs were critical during the pandemic to support the Australian community, they were also costly and not fiscally sustainable in the long term.

And further on in the Report:

Job losses at the start of the pandemic meant that labour income for the bottom decile decreased significantly. Yet substantial government support payments led to large increases in the disposable incomes of low-income households relative to middle- and higher-income households, leading to an initial decline in overall income inequality … In particular, recipients of JobSeeker initially received an additional $550 per fortnight under the Coronavirus Supplement, almost doubling the previous size of the payment …

JobSeeker is the Government’s pathetic term for the unemployment benefit.

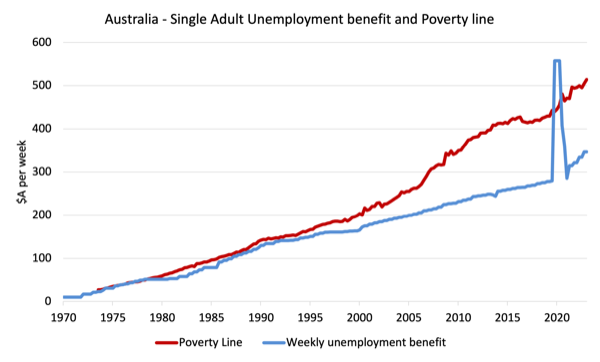

The following graph shows the evolution of the Single Unemployment Benefit and the Single Unemployed Poverty Line since 1973 until March-quarter 2023 (the last two quarters for the poverty line are extrapolated based on CPI movements).

I haven’t the time today to update this but the situation has not changed significantly in the last year.

The big spike in the unemployment benefit is the impact of the government assistance that the PC is referring to.

The Government withdrew that support soon after and returned the unemployment benefit to well below the poverty line.

The gap between the poverty line and the benefit has increased over time.

When the current government was elected in May 2022 it refused to alter the situation in any material way.

Now its right-wing neoliberal think-tank, the PC is claiming that the reversal in the income support, that had pushed the unemployed above the poverty line for the first time in nearly 4 decades, was “not fiscally sustainable in the long term.”

A related footnote in the Report repeats this assessment and then says:

The fiscal cost of JobKeeper alone was $88.8 billion in nominal terms.

$A88 billion to help the unemployed move above the poverty line.

This Melbourne Age article (May 14, 2022) – Radioactive: Inside the top-secret AUKUS subs deal – reported on the AUKUS announcement, which will involve the Australian government spending billions on nuclear submarines that will be out of date by the time they are delivered.

Much has been made of the $A368 billion sum the Government has committed, which is a very large relative commitment compared to most large projects.

The article quotes the then Treasurer responding to the concerns over the outlay figure as saying:

Everything is affordable if it’s a priority … This is a priority.

Which really gives the game away doesn’t it?

Repeat the numbers:

$A88 billion to help the unemployed move above the poverty line.

$A368 billion to build some submarines under the AUKUS agreement.

The point is that the PC offer no justification for the “not fiscally sustainable” conclusion.

They just assert it and rely on our shared ignorance that it is a big number and government cannot afford such things.

The fact is that the Australian government could move the unemployed above the poverty line with the stroke of a computer keyboard.

The fiscal injection that would be needed would be the tiny relative to the overall spending plans and would not make much of a dent in the spending gap that the fiscal surplus is making worse.

No-one else would know the difference yet the unemployed and their families would enjoy a much more secure life.

The fact is that the Australian Labor government does not prioritise the well-being of the unemployed.

As Labor governments go, they are a disgrace.

Conclusion

I also noted a UK Guardian report that talked about these issues and I won’t link to it because it just takes the readers down another irrelevant rabbit-hole.

It agrees that the government ‘could afford’ to improve the unemployment benefit.

Why? Well according to the journalist because they could tax some things more.

And at that point, the reader is just getting the ‘government can run out of money’ narrative reinforced.

Pathetic really.

It is obvious that government has the choice to end poverty or not.

The interventions during the early years of the pandemic demonstrated that beyond doubt.

Now, they are choosing to not reduce poverty but also to push more people into poverty.

That is a shocking indictment of a Labor government.

Advance orders for my new book are now available

I am in the final stages of completing my new book, which is co-authored by Warren Mosler.

The book will be titled: Modern Monetary Theory: Bill and Warren’s Excellent Adventure.

The description of the contents is:

In this book, William Mitchell and Warren Mosler, original proponents of what’s come to be known as Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), discuss their perspectives about how MMT has evolved over the last 30 years,

In a delightful, entertaining, and informative way, Bill and Warren reminisce about how, from vastly different backgrounds, they came together to develop MMT. They consider the history and personalities of the MMT community, including anecdotal discussions of various academics who took up MMT and who have gone off in their own directions that depart from MMT’s core logic.

A very much needed book that provides the reader with a fundamental understanding of the original logic behind ‘The MMT Money Story’ including the role of coercive taxation, the source of unemployment, the source of the price level, and the imperative of the Job Guarantee as the essence of a progressive society – the essence of Bill and Warren’s excellent adventure.

The introduction is written by British academic Phil Armstrong.

You can find more information about the book from the publishers page – HERE.

It will be published on July 15, 2024 but you can pre-order a copy to make sure you are part of the first print run by E-mailing: info@lolabooks.eu

The special pre-order price will be a cheap €14.00 (VAT included).

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2024 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.