At risk of piling onto an already devastating week for the EA movement, I’ve been meaning to explain why I am not an Effective Altruist. As I mentioned on Twitter, I plan to get back to writing about Mormonism and other topics the moment the national Adderall shortage subsides — a shortage that recent revelations suggest the EA movement may itself be contributing to. Fortunately, EAs love reading ponderous essays, which relieves me of my usual writer’s anxiety. So if it’s true that most books can be condensed into “a six paragraph blog post,” I’ll spare you the filler and try to limit myself to at most four books’ worth.

Where do abstract moral concepts derive their motivational power? EAs love to debate normative ethics, and produce voluminous musings about how to apply their favorite abstract moral framework, consequentialism, in different settings. Some, such as the notorious SBF, bite the bullet and adopt the crudest version of utilitarianism without exceptions. Most normal people, however, recognize there are situations where a vulgar utilitarian calculus breaks down — so-called “edge cases” where “side constraints” kick in, such as respect for human rights. For example, while most people see the logic of killing the one to save the five in the classic Trolley Problem, most EAs (though, regrettably, not all) reject the idea of a doctor secretly killing a patient undergoing routine surgery to harvest their organs and save five others. In both cases, 5 is greater than 1, and yet the second scenario triggers a deep sense of dissonance with the constellation of our other moral commitments.

As the philosopher Charles Taylor pointed out, and as Joseph Heath explains in the video above, this suggests the pragmatic force of a moral proposition exist prior to whatever normative framework it’s couched in. The motivational oomph of morality instead derives from the concrete social practices that institute norms through our mutual recognition of their validity. Norms undergo evolution and refinement as a community stumbles upon instances where their normative commitments are materially incompatible, similar to how the common law evolves by judges reconstructing the principles behind conflicting or incomplete precedents. So why not ditch the moral gerrymandering and argue for a principle directly from what grounds it?

Language lets us make explicit the implicit, and bring our pre-conventional mores, customs and patterns of rule-following under rational control. Abstract moral frameworks are thus nothing more than expressive devices which, in their mature incarnation, provide rich vocabularies for extrapolating and reconciling otherwise inchoate imperatives. Supposed “theories” like consequentialism do no actual justificatory work, but instead inherit their moral force from the concrete commitments they’re abstracted from. EAs (and most moral philosophers, for that matter) mistakenly flip this order of entailment, as if the theory underwrites the practice and not the other way around — what the pragmatist philosopher Robert Brandom calls “the formalist fallacy.” In the extreme, theories like utilitarianism reify one narrow set of commitments (reduce suffering; weigh the consequences) out of a much broader diversity of goods, resulting in a hypertrophied moral faculty that’s often indistinguishable from having no moral faculty at all.

Construal level theory refers to a set of findings in psychology related to how people conceptualize things differently based on spatial, temporal and interpersonal distance. When things are distant, we tend to be more abstract and idealistic; our mental “far mode.” When things are close, our “near mode” helps us focus on the practical and particularistic. EA and rationalist discourse tends to privilege the “far mode,” a topic Robin Hanson has written on for years, but it’s at best only half of the equation.

The near-far ways of construing the world exist for a reason: they are a product of our brain’s evolution. And a central lesson from evolutionary psychology is that our mental modules must have served a function specific to a certain domain. Near and far modes of moralizing, much like fast and slow modes of thinking, are thus specialized to their level of construal. You shouldn’t try to take their golden mean. Rather, one must employ each mode at its appropriate level or risk making a moral category error.

For example, when it comes to macroeconomic policy, the only intelligible framework is really a broadly utilitarian one. So switch on your far mode: we are dealing with an economy’s “big picture” and have no choice but to be abstract, impersonal, calculating, and analytically egalitarian. There is no such thing as “virtue based monetary policy,” nor a deontological theory of public debt (Germany’s treatment of Greece notwithstanding). Nonetheless, duty and virtue still matter at the institutional and characterological levels. We want a central bank chair-person who practices prudence and self-control while fulfilling the patriotic and fiduciary duties of their social role. So switch on your near mode, because living your life as a pure utilitarian is simply not psychologically possible.

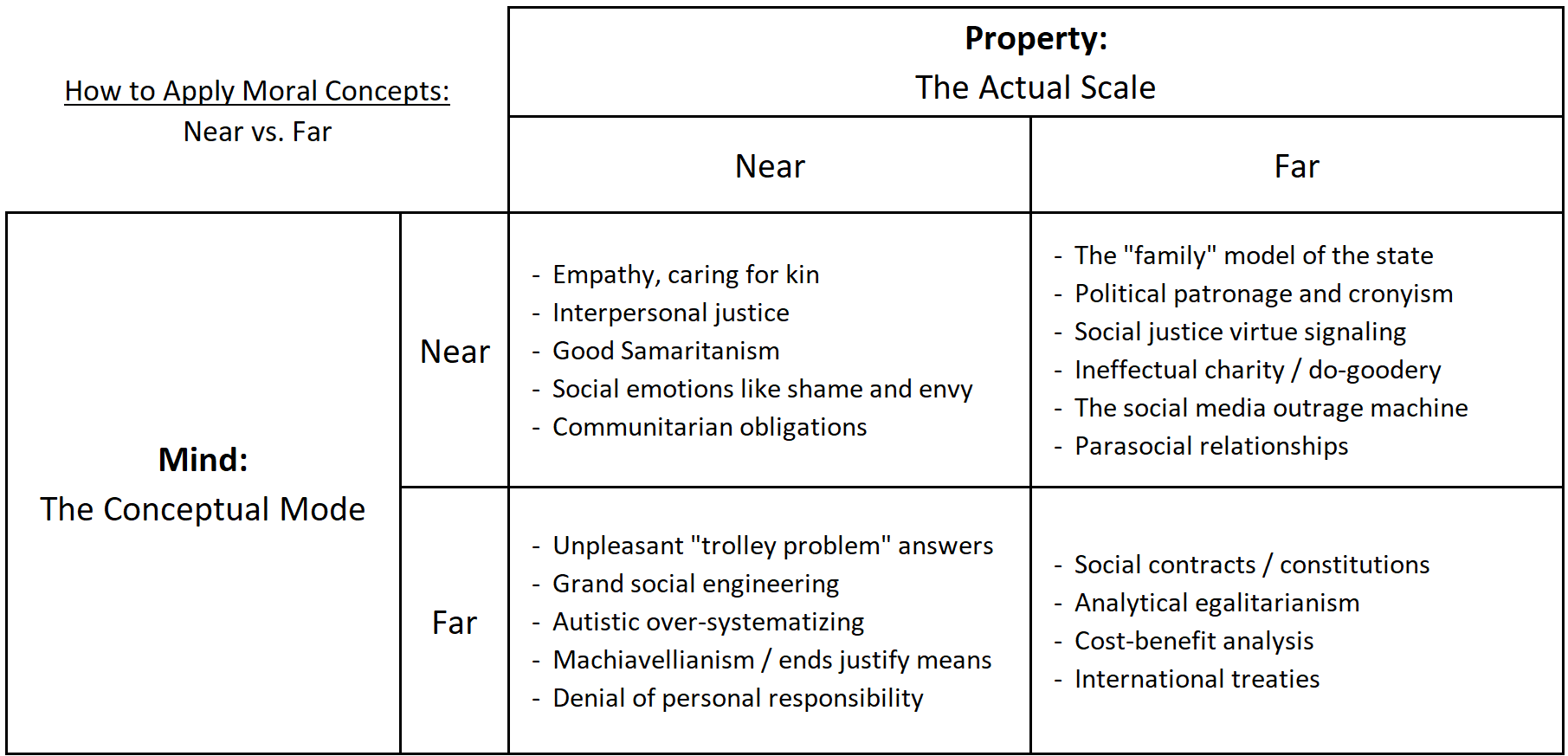

An ethical life thus requires embracing a kind of moral gestalt: sometimes we need to moralize about the forest, while other times we need to moralize about the trees. Taking the average of the two modes will leave your worldview a blurry mess, while applying the far mode to near problems (or vice versa) leads to the pathologies outlined in the table below:

Whether or not you’re a moral realist who believes certain moral claims are objectively true (I’m more of a constructivist), there are many moral claims everyone can agree are clearly false. Accusing a deadly hurricane of murder is nonsensical, for example, since intentional properties don’t supervene on the weather. Unfortunately, our agency detection system is notoriously overactive. The Bible attributes divine condemnation to plagues and floods, and when you stub your toe on a chair for a split second your anger is directed at an inanimate object.

Similar errors occur in the political domain. Hayek famously argued that many theories of “social justice” are atavistic, i.e. fit for a small tribe of hunter-gathers. Most intuitive concepts of blame and fairness simply don’t supervene on whole collectives. Conversely, in applying a far concept to a near modality, others misappropriate the evidence for structural and biological determinism to conclude that we need to move “beyond blame” and the concept of personal responsibility altogether.

At its best, the EA movement offers a corrective to these kinds of category errors, pushing public policy and private philanthropy away from virtue signaling and towards a scale-appropriate sensitivity to scope. At its worst, EAs are Charles Dickens’ telescopic philanthropists, individuals “whose charitable motives [are] to serve their own vanity by high-status projects in exotic and faraway places, while ignoring less prestigious problems at or near home,” like when dozens of EAs apply for the same open position at the State Department.

The subset of EA thinking known as “longtermism” all but embraces the telescope, peering far off into the distant future while our institutions crumble in the present. As a self-conscious maxim, longtermism really only makes sense for an omnipresent social planner. It calls for treating all future people on equal moral footing with currently existing people. And since future people radically outnumber current people, that means being monomaniacal about boosting GDP, preventing existential risks, and avoiding anything that might destabilize civilization. Of course, this puts longtermism in immediate conflict with naïve utilitarianism, as repeated all-or-nothing coin flip bets are anything but lindy.

Ironically, from a longtermist perspective, widespread exposure to EA thinking may even be an information hazard. Actually-existing longtermist societies tend to be oriented around order and tradition, wary of knocking down Chesterton fences, and connected to the distant future insofar as they maintain continuity with their ancestral past. Practical longtermism is thus a civilizationalist program, not a utilitarian one. The Imperial House of Japan comes to mind, the oldest continuous hereditary monarchy in the world, dating all the way back to 660 BCE.

The economist Tyler Cowen endorses a version of longtermism in the book, Stubborn Attachments, based on his argument for a zero social discount rate. This is equivalent to treating all future people on equal footing, and implies centering ethics around whatever achieves sustainable, long-run economic growth. Yet in expounding on the second-order implications of a zero SDR, Cowen winds up finding religion. That is, even if longtermism is true, it may not be in humanity’s interest for ordinary people to believe in longtermism as such. We should instead be rooting for the “commonplace,” if not widespread conversion to Mormonism given their synthesis of pro-growth theology with anti-fragile communitarianism.

Cowen took several decades to finish Stubborn Attachments and was more forthright about his project in earlier drafts. The (since deleted) outline from 2003 is titled “Civilization Renewed: A Pluralistic Approach to a Free Society,” and declares that “warding off decline should be a central goal, if not the central goal, of political philosophy.” While Stubborn Attachments is framed in consequentialist terms, I think these earlier drafts make a much stronger case precisely because, as Cowen notes, they avoid “being trapped by the standard difficulties of utilitarianism, including its collectivistic slant, its extreme demands on individual lives and talents, and its frequently counterintuitive moral implications.”

Per Arnold Kling’s Three Languages of Politics, Cowen’s civilization-to-barbarism axis is quintessentially conservative. Indeed, a stubborn commitment to sustained economic growth has many transparently right-wing implications. In particular, to the extent there’s a policy trade-off between growth and equity, we should firmly side with growth. Trade unions, for example, don’t just redistribute rents within a firm, but also across time, privileging the wellbeing of current workers over the future workers harmed by forgone productivity gains (take the industrial revolution, which was both a cause and consequence of the breakdown of Europe’s old guild systems).

If anything, policymakers should redistribute resources to the rich given their higher rates of savings and investment. As Cowen writes in Stubborn Attachments, “redistribution to the rich will be anti-egalitarian at first, but over a sufficiently long time horizon the poor will increasingly benefit from the high rate of economic growth.” This may sound implausible, but is essentially the East Asian developmental model pioneered by Japan, Korea and China — countries which all paired export-oriented market reforms with labor repression and policies to redistribute household consumption into aggressive business investments. Similarly, Cowen argues, “given the limits on our obligations to the poor, we will have comparable limits on our obligations to the elderly.” I thus asked EAs on Twitter whether they thought the US should abolish Social Security — a multitrillion dollar insurance program for relatively rich Westerners — in favor of spending on foreign aid. No one took the bait, but to this day, Korea stands out for its threadbare pension system and thus high rate of elder poverty. You may not like it, but this is what peak longtermism looks like:

My own contribution to this debate is to argue that, contra the growth-equity trade-off, robust social insurance programs are both a condition and accelerant of sustainable economic growth. Yet the normative logic of social insurance is Paretian, reflecting the contractarian imperative to efficiently compensate the potential “losers” from creative-destruction, and thus isn’t merely instrumental to growth.

The preference-neutrality and positive-sum logic of a Pareto improvement makes it easily confused with utilitarianism, but the two have quite different implications. Utilitarianism is top-down, positing a social welfare function to be maximized, a la Bentham or Pigou. Paretians, in contrast, start with the bottom-up process of exchange and transaction, a la Ronald Coase or Elinor Ostrom. Two people will only exchange goods or services if each perceives a net benefit from doing so — that is, if the trade will move them toward a Pareto improvement or win-win outcome. This is at the heart of bargaining theory and how de jure property rights emerged in the first place.

Paretianism also provides a solution to the “tragedy of common sense morality” or any scenario where conflicting interests or value systems collide, such as the Acts of Toleration that emerged in the ruins of Europe’s wars of religion. Thus, whereas Cowen’s defense of human rights tries to “pull a deontological rabbit out of a consequentialist hat,” a Paretian can easily reconcile our dual attachments to economic efficiency and political liberalism as derived from the common principle of mutual advantage.

In turn, Paretians can resolve the apparent reductios that arise from treating spatial and temporal distance as moral illusions, justifying both a positive time preference and the privileged status that nation-states’ assign to the interests of their citizens. This calls back to the two arguments outlined in the sections above: that moral obligations must be appropriately construed and institutionalized in cooperative social structures, rather than derived from some cosmic standpoint that only exists in what Hegel once called “the errors of a one-sided and empty ratiocination.”

In my day job at a think tank, I care a lot about how public policy can do the greatest good for the greatest number. In that context, I’m not that far off from your typical EA. My work on child allowances, for example, is directly influenced by EA thinking on the superiority of cash transfers for alleviating poverty. I’ve also done work on EA-adjacent causes like organ donor compensation and regulatory reforms to unleash breakthrough technologies. Moreover, I believe any effective policy entrepreneur must have a realist view of political economy, a sense of which issues are neglected but tractable, and a strategic focus on results.

At the same time, I follow a basic set of professional ethics, such as being guided by the evidence when assessing a policy debate, rather than bending evidence to fit an activist agenda or to appease my funders. Nor do I steal my coworkers’ lunch from the office fridge, even if donating it to the homeless man outside would increase utility on net. EAs thus go most wrong when they try to embody a far conceptual mode in daily life, stripping moral obligations of their institutional embeddedness. As a result, the EA movement often looks more like a kind of virtue ethics for nerds: ethical veganism, “earning to give,” the life you (specifically YOU) can save. Have you donated your kidney to a stranger yet?

Of course, from an actual consequentialist perspective, this is all an enormous category error — mapping far scale problems like global development and industrial farming to near evaluations of individual behavior. Norman Borlaug was arguably the most effective altruists of the last century, helping develop high-yield, disease-resistant wheat varieties that saved a billion lives from starvation. He was partially motivated out of concern for the poor, but ultimately succeeded because he focused on being a damn good agronomist. From an EA perspective, he could have lived out the remainder of his life punching babies and still have been a net positive for the world. That’s because consequentialism is about integrating over outcomes, not intentions; and outcomes are a system level property that few are ever in the position to self-consciously control. On the contrary: nothing has done more for humanity than the widespread adoption of property rights and free markets; social technologies for aligning selfish motives to positive-sum outcomes. To paraphrase Adam Smith, it’s not from the effective altruism of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner.

It’s thus not surprising that some have likened the EA movement to a religion. Donating a chunk of money to GiveWell every pay period is basically tithing for affluent secularists. Yet while EAs are disproportionately non-religious, they are surprisingly blind to the Christian genealogy of their morals, believing they arrived at their convictions through a persuasive book or LessWrong sequence rather than the inherited normative presuppositions of the culture they grew up in. In a now legendary interview, Tyler Cowen once put this point to Peter Singer directly:

My reading is this: that Peter Singer stands in a long and great tradition of what I would call “Jewish moralists” who draw upon Jewish moral teachings in somehow asking for or demanding a better world. Someone who stands in the Jewish moralist tradition can nonetheless be quite a secular thinker, but your later works tend more and more to me to reflect this initial upbringing. You’re a kind of secular Talmudic scholar of Utilitarianism, trying to do Mishna on the classic notion of human well being and bring to the world this kind of idea that we all have obligations to do things that make other people better off.

The term “altruism” itself was first coined in the 1850s by the French sociologist and founder of positivism, August Comte — truly the Scott Alexander of his day. Positivism extolled a kind of scientific naturalism but needed an ethical system to go with it. Comte thus founded a rationalist cult called the “Religion of Humanity”: a proto-EA movement that sought to rid Christianity of its superstitions while retaining its moral precepts, including asceticism, a belief in “vivre pour autrui” (living for others), and a melioristic commitment to worldly improvement. It was a fullstack religion, with sacraments and rituals, as well as prayer services based on “a solemn out-pouring … of men’s nobler feelings, inspiring them with larger and more comprehensive thoughts” — not unlike the EA meetups I’ve been to. Members wore robes that buttoned from the back, necessitating the help of another, while the priests were to be “international ambassadors of altruism, teaching, arbitrating in industrial and political disputes, and directing public opinion.” MDMA-fueled polycules and New York Times bestsellers would come much later.

Yet calling EA a religion isn’t meant as a knock. As David Foster Wallace said, “Everybody worships.” In fact, the religious structure of the EA movement may be the best thing going for it, ensuring its high-minded ideals are embedded within, and reproduced by, a living ethical community. There’s clearly an appetite among smart young people to adhere to a system — any system — that integrates and orients their desire for social impact. So while one might prefer that EAs all became Mormon, as a pluralist with an appreciation for the “second best,” it could be a lot worse. At least they’re not woke!